HSJ’s expert briefing on NHS finances, savings and efforts to get the health service back in the black.

Damage limitation

The normally upbeat NHS Improvement seems to have lost its confidence.

Three months ago, the regulator’s report for the first quarter of 2017-18 proclaimed a “very strong… very encouraging” start to the financial year.

But in its report on the second quarter, published just before the budget, the regulator sounded more like it was in damage limitation mode: “While huge strides have been made in improving the NHS provider sector’s financial position, so far this year NHS trusts and foundation trusts are collectively predicting a full year deficit of around £623m – £127m worse than planned.

“This does not include additional pressures and potential spending needed to meet them over the coming winter months.”

These comments were not hidden away but at the front of the report.

Meanwhile, more detailed sections included observations that sounded more like the Nuffield Trust than NHSI – talking about “backloaded” savings plans and last year’s position being “highly dependent on non-recurrent items [that did] not address the longer term financial sustainability of many providers”.

Where has the optimism gone?

Given all these risks were clear three months ago, the change in tone perhaps comes down to politics.

In August, NHS England and NHSI were telling a positive story of financial improvement, in the hope it would be rewarded in the budget.

But when it became clear they wouldn’t be rewarded as generously as they’d hoped, Simon Stevens broke ranks and NHSI decided to get real.

The mighty CQUIN

Other pressures have also materialised.

Within their plans, most providers have assumed they will receive £270m of CQUIN incentive payments from their commissioners, which are being held as part of the national “risk reserve”.

But I understand NHS England, which ultimately controls this pot of cash, has been signalling the risk reserve is under pressure at national level due to higher than anticipated deficits among clinical commissioning groups.

From the sounds of it, around half of the CQUIN fund is likely to be held back from trusts, which would automatically add £130m to the provider deficit and potentially lead to more missed payments from the sustainability and transformation fund.

Looking at the actual mid-year deficit, and the risks involved in the plan, it is extremely likely the trust sector will end 2017-18 in deeper deficit than last year.

It might well have been worse had Jim Mackey not been patching things together for NHS Improvement – but the clue is in the name and the expectation was for improvement.

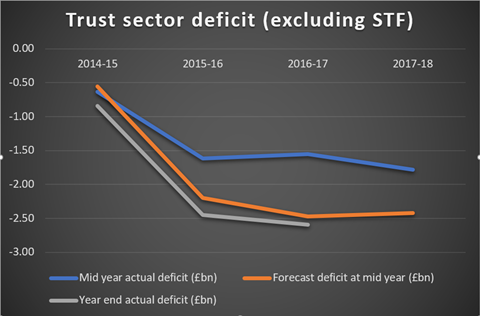

Although the orange line in the graph below suggests a small improvement compared to last year, it shows the forecast position and assumes everything goes right until April. The blue line shows the actual year to date deficit worsening after some improvement last year. The non-recurrent STF has been removed to enable comparisons between financial years.

Revising the position

Assuming the government continues to expect an upward trajectory on elective and emergency waiting times, the extra revenue announced in the budget will do little to shrink the deficit.

It has been clear for months the financial trajectories within the Five Year Forward View are “off plan” and it surely can’t be long before we see official revisions to the assumptions.

The catch

As predicted in September, the extra capital funding in the budget comes with a catch.

Alongside the £3.5bn of new investment, the Treasury documents said there would be work to “review and improve the rules that inform trusts’ use of capital funding”.

The days of foundation trusts enjoying the freedom to set their own capital spending plans are likely to be numbered.

Eyes on the cash

Beneath the deficit problem that has occupied so much attention, dozens of trusts are running out of cash.

HSJ’s analysis of performance against the Better Payment Practice Code shows more than a quarter of hospital trusts are routinely failing to pay their suppliers within 30 days, with a threefold increase in acute providers paying more than half their invoices late.

Barking mad

One of the trusts reporting a steep decline in timely payments is Barking, Havering and Redbridge University Hospital Trust, which is having its finances investigated by NHSI.

Problems have mounted further for BHRUHT in the last week, with a group of consultants writing to the chair to say they have “lost confidence in the approach of the current executive leadership”.

The trust’s senior medical staff committee says it is “extremely concerned” about the sudden cash flow issues and is dissatisfied with the level of engagement between doctors and the trust’s management.

Learning from mistakes

Further problems have also arisen at Oxford University Hospitals Foundation Trust, another provider whose finances are being investigated.

For the second year in a row, the trust has reported a dramatic collapse in its financial performance, with an expected deterioration of £24m against the planned surplus position. Last year the trust finished £23m worse than planned.

Something has gone badly wrong with the financial planning and governance at OUH over the last two years and regulators will want to know why lessons were not learned.

2 Readers' comments