Science fiction is set to become reality as digital patients reveal how individual people will be affected by disease. Shreshtha Trivedi reports

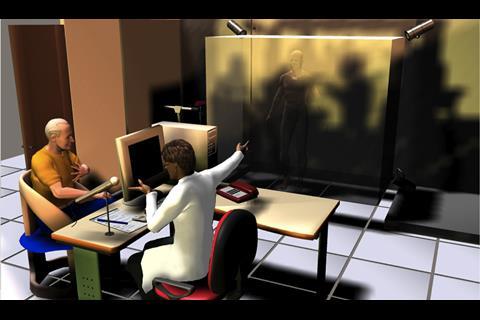

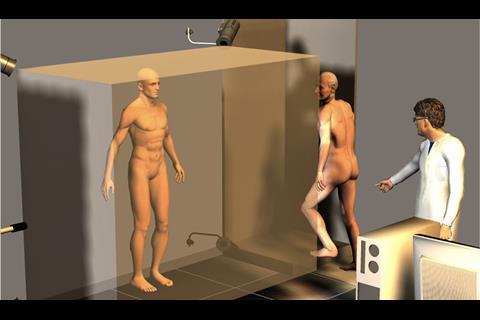

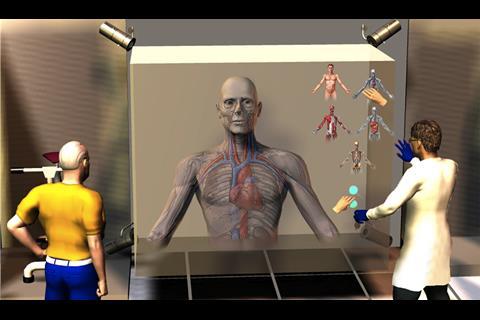

Soon it might be possible for doctors to accurately predict how diseases will affect patients in the future by creating their virtual replicas.

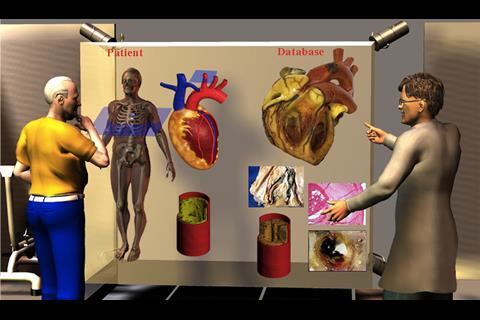

This may seem like science fiction but it is set to become reality with the launch of Virtual Physiological Human – an online reproduction of the entire human body using supercomputers.

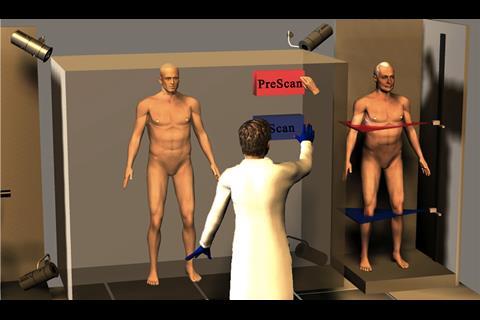

This “digital patient” will be tailored to the needs of an individual, providing personalised care that accounts for his or her medical history, lifestyle, physical constitution and genetic makeup.

Gaze into the future

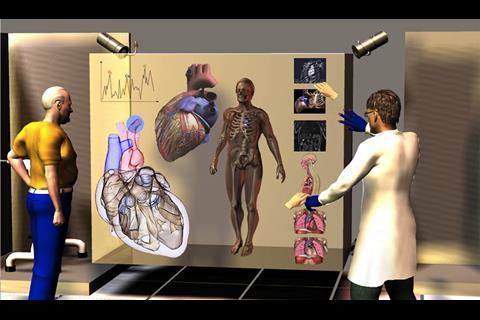

There is a great amount of information about the workings of individual body parts but there has been no way of understanding how they function in an integrated way. These specialised computer models will allow doctors and clinicians to see how different organs of the body function together and how diseases will affect someone over the period of time.

‘The technology will make it possible for doctors to make health forecasts and enable patients to “gaze into their future”’

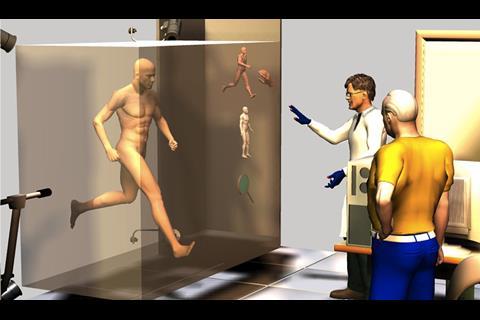

The technology will make it possible for doctors to make health forecasts and enable patients to “gaze into their future” – what will happen if they follow or don’t follow a certain lifestyle, how will their hearts look in 10 years and how will ageing affect their bones?

This has the potential of not only improving health but also preventing diseases and, ultimately, moving towards the concept of patients being partners and taking charge of their own health.

With ageing populations being a source of concern across the UK and developed nations, this model of integrated care hopes to reduce the pressure on hospitals and move some of the operations into primary and community settings.

Translating research into practice

The VPH initiative is a brainchild of Insigneo Institute, a collaboration between Sheffield Teaching Hospitals Foundation Trust and University of Sheffield. Started two years ago, the institute was officially launched last month. It has more than 80 researchers and clinicians working towards a goal of translating research developments in the field of biomedical modelling and informatics into clinical practice.

With £10m of research funding – and an application for a further £35m – it is one of the largest research initiatives in this field in Europe.

Professor Marco Viceconti, Insigneo’s scientific director, defines VPH as a “framework of methods and technologies that will make it possible to investigate the human body in a more integrated way, taking into account all the different processes that are happening at the same time”.

He says: “Not only will the VPH give us a better understanding of how life works, it will enable doctors and clinicians to look at the whole body as one entity again, focusing on treating the patient rather than developing specific cures for specific diseases.”

Uncharted territory

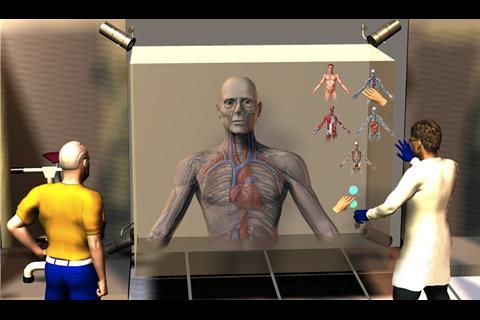

Some of the key areas of focus under the VPH initiative are:

- research into the musculoskeletal system;

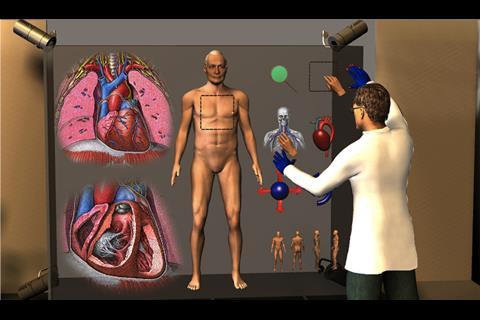

- the assessment of heart diseases by constructing a 3D model of the heart; and

- the creation of personalised models of brain aneurysms.

Professor Eugene McCloskey, honourary consultant at Sheffield’s metabolic bone centre, says: “The research has focused on simple things that we can measure such as diseases like osteoporosis. These are so common that they should be managed, ideally, in primary care. But the tools we have right now are blunt and simple. We can do more detailed assessments [of bones and the musculoskeletal system] and take that to the wider community.”

‘The experts unanimously agree that the benefits of this technology in the long run would far exceed the costs’

On the question of cost-effectiveness – and whether the NHS would eventually make use of such an elaborate model on a large scale in these times of austerity – the experts unanimously agree that the benefits of this technology in the long run would far exceed the costs.

Last year, 4 million people in Europe suffered a fracture due to osteoporosis, at a cost of €30bn. Coronary heart disease remains the world’s biggest killer.

Professor Wendy Tindale, consultant clinical scientist and scientific director at Sheffield Teaching Hospitals Foundation Trust, says: “Since the VPH programme will provide patient targeted information, it will improve the quality of care by avoiding wasteful treatments and thereby save money.”

Dr Julian Gunn, consultant cardiologist at the trust and a senior lecturer at the University of Sheffield’s Department of Cardiovascular Science adds: “The cost of the trial [for the virtual heart prototype] is about £700,000 and it is a solid investment by the Department of Health, Wellcome Trust and the British Heart Foundation.

“It will bring cost effectiveness to patient care as the patient will receive precisely the treatment they need – not more, not less. They will avoid having unnecessary stent insertions, which cost money. They will also avoid unnecessary bypass operations, which cost even more money.”

Professor Viceconti says the trust is a partner in the project as it wants the programme to translate into clinical practice and be commercially viable. He adds: “Ultimately, we want to make a difference to the lives of the patients.”

No comments yet