Greater priority, and appropriate resources, need to be accorded to the provision of sickle cell and thalassaemia services, argue Simon Dyson and Karl Atkin

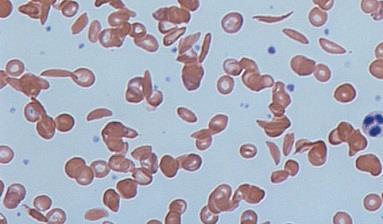

Sickle cell and thalassaemia disorders are among the most common genetic conditions in the world. In the UK, the condition affects about 15,000 people of all ethnic backgrounds but is more common in people of black African or African-Caribbean, Mediterranean and Asian origin.

‘There are encouraging moves towards networks of clinical care based around centres with medical and nursing staff with specialist knowledge’

Yet legitimate questions about the lack of priority accorded to them remain. Why are clinical networks of care only just being formalised for SCD, when a network of specialised centres for haemophilia has been long established?

Why do genetic carriers of rare clinical conditions receive two hour genetic counselling sessions when sickle cell/thalassaemia carriers might be allocated 20 minutes? Why does cystic fibrosis (which in England affects 10,000 people, compared with 15,000 with sickle cell disorders) garner more than 30 times as much financial support as sickle cell disorders?

It has taken sickle cell disorders to be five times as common as phenylketonuria in newborns for the equivalent comprehensive newborn screening programme to be in place. It affects one in 10,000 newborns and we have had screening of all babies for it since the 1960s. As of today, one in 1,900 of all babies born have a sickle cell disorder: five times more than have phenylketonuria.

Service improvements

Since the Runneymede Trust audited SCD service provision in 1985, in Sickle Cell Anaemia: Who Cares?, there have been undoubted improvements in service provision. Newborn screening of all babies for SCD permits treatment with penicillin, vaccinations and scanning to reduce risk of strokes in children with sickle cell disorders. There are encouraging moves towards networks of clinical care based around centres with medical and nursing staff with specialist knowledge. But much remains to be done.

‘People living with SCD still feel not listened to, stereotyped as drug seekers, insulted by terms such as “frequent flyers”’

The interface between identifying infants with SCD and ensuring their best care still needs strengthening and requires auditing against standards. In 2008, care of adults was shown to be problematic by the National Confidential Enquiry into Patient Outcome and Death, which found that lack of referral to specialist staff, lack of monitoring subsequent to administration of morphine for severe pain, and failure to consider reasons other than their sickle cell that a patient with SCD might be ill, had all contributed to unnecessary deaths from SCD.

Campaigning for “more SCD services” need to be more nuanced. European and World Health Organization policymakers tend to emphasise “prevention”, “control” and prenatal screening. About 10 per cent of foetuses with SCD currently end in termination of pregnancy. Communities, however, want more services directed to the care of those living with SCD.

Patient complaints

The problems sometimes arise with non-specialist staff. The curriculums of medical, nursing and allied health professions should be required to demonstrate how precisely they equip all their future professionals to care for SCD, especially as SCD no longer meets the threshold (1 in 2000) where it can be considered rare.

The cases of three year old Obed-Edom Bans, sent home from an NHS walk-in centre, and university student Sarah Mulenga (ambulance staff refused to take her to hospital), both of whom subsequently died, demonstrates the need for all NHS staff, including in primary care, to be aware of SCD.

However, it is not merely a question of education. Numerous educational resources already exist, including national guidelines on the treatment of patients with SCD and thalassaemia.

The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence has guidelines on managing pain, one of the sources of most patient complaints about services, where people living with SCD still feel not listened to, stereotyped as drug seekers, insulted by terms such as “frequent flyers” or dismissed as having low pain thresholds.

Culture shift required

But a cultural shift among healthcare professionals is required. What has been lacking, as the government’s chief medical officer Dame Sally Davies said more than 20 years ago in her commentary on the Standing Medical Advisory Committee Report on Sickle Cell, Thalassaemia and Other Haemoglobinopathies, is for government to both to fund and to make mandatory the services and standards we know are required.

‘Progressive clinical commissioning groups are beginning to commission services from voluntary groups’

This brings us to the role of commissioners, who frequently are unfamiliar with the complex needs required of SCD and thalassaemia services. The move to include clinical care under specialised commissioning services at a national level is welcome, but leaves many unanswered questions.

The excellent work of specialist sickle cell and thalassaemia nurses, both clinical specialists and specialist nurse counsellors, is not only the element of service provision most frequently and highly praised by patients and families, but the sheer complexity of their role, combining clinical and counselling skills with advocacy work around housing, education, employment, social security and insurance is the most multifaceted role of any equivalent specialist workers in the NHS.

Such nurses have crucial roles to play in enhancing self-management skills of patients, preventing expensive hospital admission and in addressing social issues that may have clinical consequences.

Progressive commissioning

A minimum staff-to-patient ratio of around 1:40 is needed. Were this applied across the country we would immediately see how such a vital and effective professional group has been underfunded.

We also need to recognise that national and local voluntary organisations play a vital role: they are embedded in the communities they serve. Progressive clinical commissioning groups are beginning to commission services, such as community education, from such groups, yet sustaining their funding remains a constant struggle.

Government has a key role to play, but everyone has the opportunity to exert influence, in order to ensure SCD and thalassaemia are properly considered in resource allocation.

We live in times of retrenchment of services, and it becomes even more important that resources are allocated fairly. If you agree with equity for sickle cell services, then either we need to argue for greater resources overall, or that the resources that are distributed are allocated on a more equitable basis. We prefer the former, funded through general taxation.

However, if you insist on the latter, then be prepared for arguments that we need fewer consultants and nurses in specialties where they have been historically allocated, and more in the service of patients with sickle cell and thalassaemia.

Find out more

Simon Dyson is professor of applied sociology at De Montfort University and Karl Atkin is professor at the health sciences department at York University. The authors acknowledge the work of Economic and Social Research Council Funded Project RES-062-23-3225.

3 Readers' comments