Commissioning support units could become influential in commissioning strategy, but there is still much we don’t know about them, writes Veronika Thiel

Commissioning support units are set to take on important functions in the new NHS structure. They will support clinical commissioning groups by providing business intelligence, health and clinical procurement services, as well as back-office administrative functions, including contract management.

‘Compared to CCGs, there is little or no information about CSUs’ current state of development from the board’

The current policy intention is to introduce competition into this market by making them independent businesses from 2016. Until then, they will be hosted by the NHS Commissioning Board, which will also employ their estimated 6,000 to 8,000 staff. The extent to which CCGs will use CSUs is likely to vary greatly.

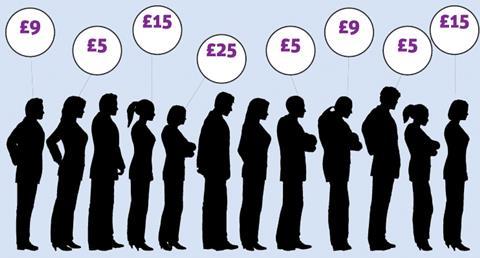

Research by HSJ in January found some groups will do the bulk of commissioning in-house, with two spending only £5 of their per capita £25 management allowance on external commissioning support. Others intend to rely more heavily on support units, with Corby and Ashford CCGs spending £15 per head.

On average, CCGs will spend £9 per head. Some CCGs have also entered long-term service level agreements of five years, whereas others are sticking to the commissioning board guidance of 18 months.

However, a few weeks before the new system goes live, there are still many unknowns and little clarity around definitions. For example, contract management can be anything from making sure everyone signs on the dotted line to carrying out detailed negotiations.

Strategic influence

Similarly, CSU involvement in service design may be limited to an advisory or communications role, or stretch to engaging in the design of services. While decision making responsibility and accountability for what to commission remains with CCGs, it is clear that CSUs could heavily influence long-term strategy.

This mixed picture is not helped by a lack of transparency. Compared to CCGs, there is little or no information about CSUs’ current state of development on the commissioning board website.

‘The current tendency for longer-term agreements between CCGs and CSUs is probably a positive step’

Although they will be part of the NHS until 2016, they do not appear on a recent Department of Health diagram of the new NHS structure either. Even finding a list of CSUs in the pipeline requires much digging, never mind finding out who runs them.

As the main commissioners and bodies accountable to the public for service delivery, there has been a strong focus on CCGs. In comparison, the support units have been the subject of little regulation and guidance.

The lack of direction on their purpose makes relationship building difficult for both CCGs and CSUs. Also, as HSJ found in its research, some groups do not wish to disclose their service level agreements with CSUs for reasons of commercial confidentiality.

While confidentiality issues in the NHS are nothing new, implementing parts of the reforms behind closed doors appears to go against the promise of greater accountability and transparency.

Crucial relationships

Some CSUs are staffed by experienced primary care trust employees, but their roles will have changed, especially if they are moving from a public PCT to a for-profit CSU. There are likely to be unintended consequences as a result of inexperience in contract negotiations.

Getting contracts right will be key. The good news here is that CCGs can learn from the experience of PCTs and their use of external commissioning support. Under the framework for procuring external support for commissioners introduced in 2007, PCTs were encouraged to outsource some commissioning functions and to buy in specialist services.

‘Given the influence CSUs may have on future commissioning decisions, they should come under much greater scrutiny’

The King’s Fund analysed this experience in a study published in 2010. This showed clearly that for external support to be useful, long-term partnerships focused on strategic review of commissioning goals and building the skills of staff are better than short-term contracts, so the current tendency for longer-term agreements between CCGs and CSUs is probably a positive step.

At the same time, the longer the agreement, the greater the need for clarity around goals and targets to ensure agreed aims are achieved. Some PCTs had informal discussions with potential partner organisations prior to tendering to clarify their aims and discuss what the partnership could deliver.

Building flexibility and risk sharing into contracts is also useful to achieve strategic goals if circumstances change, such as an increase in morbidity among a certain population group.

Given the stir the Health and Social Care Act has caused and the influence CSUs may have on future commissioning decisions, they should come under much greater scrutiny. Now is the time to ask the NHS Commissioning Board and the Department of Health some tough questions about how they plan to ensure these crucial relationships can flourish.

CSUs: the basics

- 23 commissioning support units are currently in development.

- CSUs are hosted by the NHS Commissioning Board. The board employs the staff and charges support units a fee for this purpose. CSUs will become independent businesses by 2016.

- CSUs will compete for business from CCGs and from the commissioning board. While their names suggest they are regionally based, they can serve any CCG in England.

- CCGs are not obliged to use CSUs, they can also choose independent sector providers.

- CSU services are expected to focus on contract management, business intelligence and health service design.

- There is some debate on the permissibility of the hosting arrangements. Some lawyers and independent providers have argued this would be akin to receiving state aid, contravening EU competition law.

Veronika Thiel is a researcher in health policy at the King’s Fund

8 Readers' comments