NHS staffing cuts have sparked alarm, but budget mismanagement may be the real issue, not NHS England’s cost-saving demands

According to many stories now appearing in the mainstream and specialist media, many hospitals are facing “catastrophic” cuts to staffing. The villain is often NHS England for making the highly unrealistic demand that trusts live within their budgets.

This HSJ story from March about the struggles to get financial balance this year warns that deeper cuts to staffing would hurt patient safety. This story points out that many areas see the only way to achieve a balanced budget is staffing cuts. Some trusts are planning sharp cuts in support staff.

The first fact that should cause some scepticism is that the NHS has something like 20 per cent more frontline staff than in 2019. So, claims that the system will see “unsafe” staffing or will have to cut services are not obviously credible especially given the tiny increases in activity those extra staff created. Many of the headline claims of cuts seem to ignore that post-covid budget boost and the big staffing increases that came with it.

Many forget that NHS financial problems are not always caused by funding cuts. Some happen after periods of budget largesse (like the 2006 crisis that cost the NHS CEO his job at a time where the national budget was rising at 6 to 7 per cent a year in real terms).

Many trusts are unable to cope with budgets that increase sharply but then stay steady. They overdo staffing increases in the generous years and then have to overcorrect. And, since staffing costs are 55 to 60 per cent of a typical hospital’s costs, staffing increases dominate the finances.

But trusts are not compelled to recruit staff, they choose to recruit staff: these are planned, not unavoidable costs.

What do trust accounts say?

I was initially triggered to explore this hypothesis by a rare mistake from Shaun Lintern (formerly of this parish). Shaun, in a thread about savings being demanded at Guy’s and St Thomas’, said “staffing costs needed to be cut by a third in the year ahead”. This was obviously wrong (as he clarified later in the thread), but it got my attention, and I started looking at the details.

The information was from an internal document circulated to staff at Guy’s and St. Thomas’ which said: “Our pay costs have risen by £150m over the last 4 years, but our activity levels have remained largely unchanged. While there may be specific reasons for this in some areas, we must reduce this overall by a third (£55m).”

(so the cut was relative to the increased costs, not the total costs).

But what is the context of that cut? The trust has an annual income nearing £2.8bn and employs more than 25,000 staff. That income (even accounting for the merger with the Royal Brompton in 2021) is up 34 per cent since 2019-20. Staff costs are up 26 per cent on a headcount up 15 per cent. Temporary staff have nearly doubled in headcount and more than tripled in cost. Total staff costs in 2022-23 were £1.6bn.

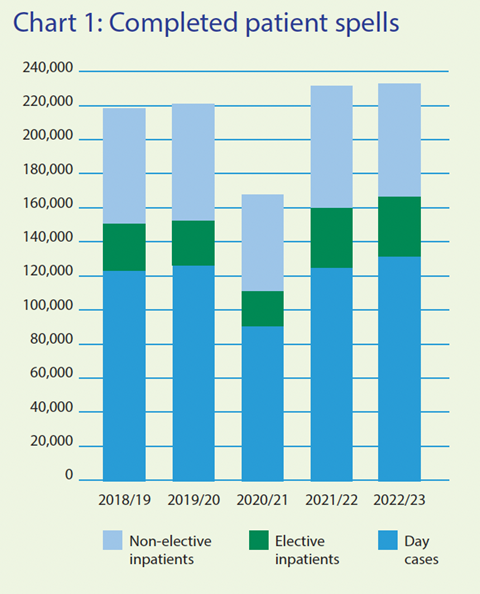

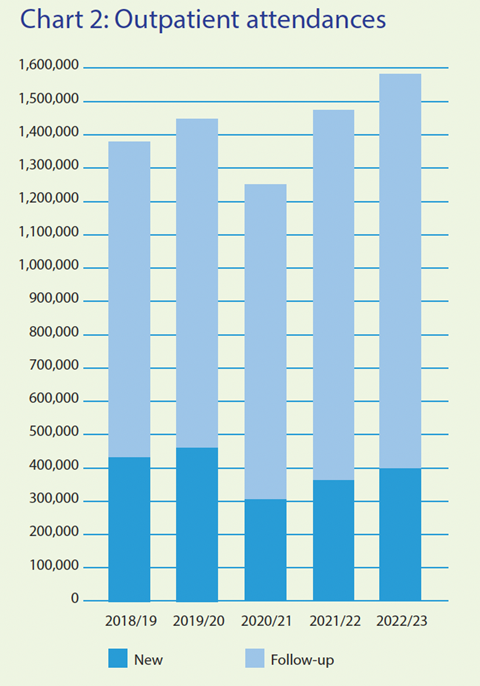

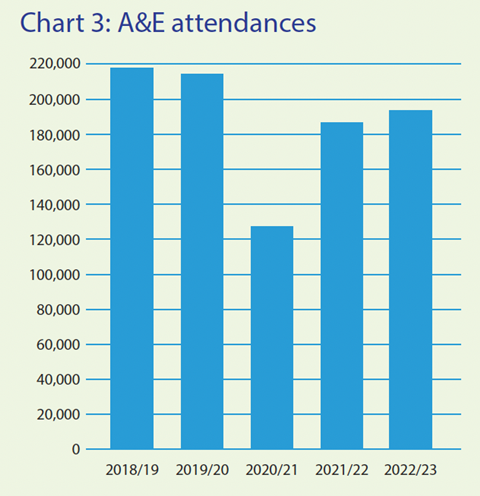

Unusually, GSTT also provide some context in their latest 2022-23 report on other changes over the period (these charts include the activity from the merger in the last two years):

Accident and emergency attendance is down 10 per cent, outpatient activity is up 10 per cent and elective activity has increased just 4 per cent. These are all substantially lower than the increases in headcount or staff costs.

I don’t wish to single out GSTT here, many other trust accounts show similar patterns.

The key takeaways from my superficial and back-of-an-envelope look at trust accounts are:

- Small percentage cuts in staff are not that significant in the context of rapid growth since before covid

- Staff increases are not driven by activity increases

My hypothesis about why everyone is now agonising about staff cuts and budget deficits is that trusts overdid recruitment when they got a big boost to their budgets after covid but forgot that the budget increase was front-loaded. Deficits are not because they have faced uncontrollable cost increases. They often chose to recruit many extra staff but perhaps failed to project the costs over the following four years when their budgets would be increasing more slowly.

And now the only solution is cuts, some of which will be better considered than others. Rapid cuts will leave a less carefully planned workforce than slower recruitment would have done (evidenced by some trusts undermining frontline productivity by chasing big cuts in support staff).

I’ve talked about the general problem of what would happen if NHSE responded with bailouts rather than a demand for cuts before and the consequences of any system with soft budget constraints.

In short, the NHS cannot spend money on long-term projects promoting productivity growth (eg capital and IT) when it constantly has to bail out trusts that didn’t plan their staff growth properly.

NHSE isn’t the bad guy here

We will see many more outraged stories about the need for staff cuts to balance the books this year. Many will blame NHSE for unrealistic goals. But they’re not the bad guys here. The NHS is impossible to manage if billions must be set aside to cover bailouts. I’m normally pretty critical of NHSE, but their insistence that budgets must be balanced is the right first step to create a foundation for future improvement.

At least they are not yet contemplating the idea proposed by the Late Bob Kerslake to run NHS trusts like local authorities with a statutory duty to break even every year. The idea seems mad at first but becomes more plausible every time trusts fail to balance their books.

10 Readers' comments