The chancellor’s announcement signalled the worst of austerity may be over, but that doesn’t mean we now have a clear plan for future public spending and reform. By Anita Charlesworth

In 1998, Gordon Brown introduced comprehensive spending reviews in place of annual public expenditure rounds. This change reflected the deep limitations of planning public services on a short-term, annual cycle. Brexit uncertainty is affecting so much of public life and this includes planning public spending; the chancellor postponed this year’s multiyear spending review and instead has announced departmental budgets for 2020-21 alone.

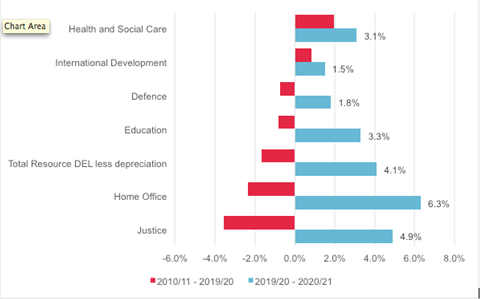

Although limited, the chancellor’s announcement may mark something of a turning point in public spending. After a decade of cuts, day to day public spending is planned to increase by 4.1 per cent in real terms next year.

But it’s not just the aggregate path of public spending that is different; the priorities for public spending also look somewhat different.

Annual average growth rate in day-to-day spending, 2010-11 to 2019-20 and 2019-20 to 2020-21

Since 2010, the NHS has been protected from the full force of austerity – health care spending grew by a fifth, while spending on other public services fell by a fifth. The police, criminal justice, social care, local government and education all suffered. From the perspective of improving health outcomes and tackling health inequalities, increasing NHS spending at the expense of other public services doesn’t make sense.

Recognition that wider public services cannot continue to be cut is welcome. But, as IFS and Resolution Foundation analysis shows, beyond health care, the additional spending reverses around a quarter of the cuts to wider public services over the last nine years. Moreover, many of the larger increases in spending for next year fall to areas that manage the symptoms of acute societal need rather than preventing need in the first place.

Rebalancing priorities

As part of the rebalancing of public spending priorities, the chancellor announced welcome extra funding for social care. This is a mix of grants from central government, and consultation on a further year of the social care precept, set at 2 per cent.

On healthcare capital, the chancellor has confirmed a spending envelope of £7bn this year and no real terms increase for next year, but a review of longer-term funding requirements to tackle the backlog of safety-critical maintenance and provide equipment upgrades and new hospitals. This further delays essential investment.

Taken together, local authorities could have up to a little over £1bn of additional funding for adult social care, depending on whether all local authorities are willing to levy a further year of precept and how they balance the pressures facing children’s and adult social care. If councils choose to spend this on top of this year’s real terms spending, then this equates to a funding increase of between 1.4 per cent and 4.1 per cent (depending on the amount raised by the precept) in real terms, compared to additional pressures of at least 3.8 per cent a year.

Depending on local decisions, the chancellor’s package should be enough to stop adult social care getting any worse next year. But it provides little headroom to tackle growing unmet need and the fundamental reform question remains on the to-do list.

With the chancellor announcing one-year budgets, we don’t know whether the new spending plans are the beginning of a process of growing and rebalancing public services or a one-off exercise to try to minimise public disquiet in a possible election year. Much will depend on the economic outlook, which Brexit makes enormously uncertain.

The OBR won’t produce new forecasts for the economy until the Autumn Budget. The generational question of how to provide decent public services with growing demand pressures from an ageing population remains to be answered. Importantly the chancellor’s announcement doesn’t say anything about social security spending, where austerity continues for working age families, risking further increases in child poverty.

For the NHS, the chancellor’s announcement is a missed opportunity to provide the investment needed to realise the ambitions of the NHS long-term plan. It doesn’t provide the scale of funding needed for the workforce, public health and capital; all of which were excluded from last summer’s long-term plan funding commitment.

The government has clearly taken the view that the long-term plan meant “job done” on the NHS. NHS England’s budget is increasing by an annual average of 3.4 per cent up to 2023-24 but next year the wider health budget is broadly flat in real terms, increasing from £8.6bn to £8.8bn in 2019-20 prices.

Healthcare funding has grown by an average of 2 per cent a year since 2010, against the backdrop of cuts to wider spending. Next year, the overall health budget (capital and day to day spending) is increasing by 2.9 per cent in real terms; less than the overall rise in public spending and below the estimated increases needed to address the lack of investment in staff and public health over recent years.

The workforce budget is set to grow by £210m in 2020-21, with a welcome proposal to increase investment in CPD for nurses, midwives and allied health professions. But this is well below the £620m the Health Foundation, the King’s Fund and the Nuffield Trust calculated would be needed to make real inroads into the nursing shortages.

For the public health grant, the Treasury has said that there will be a real terms increase but this can only happen if the Department of Health and Social Care can offset this through cuts to other central budgets. That is likely to mean a very modest rise in the public health grant, falling well short of the £1bn required to restore the last five years of cuts.

As a consequence, public health spending will continue to fall as a share of overall health spending. This defies economic logic, with new research from the University of York showing that spending on public health is three times more productive than spending on healthcare services.

On healthcare capital, the chancellor has confirmed a spending envelope of £7bn this year and no real terms increase for next year, but a review of longer-term funding requirements to tackle the backlog of safety-critical maintenance and provide equipment upgrades and new hospitals. This further delays essential investment.

Overall the chancellor’s announcement signalled that the worse of austerity may be over. But that doesn’t mean that we now have a clear programme for future public spending and reform. There are big unresolved questions about the future of health and social care and the wider public services and social security system which underpin good health.

No comments yet