This third and final report from the commission sets out obstacles to improving care and puts key questions to politicians, citizens and providers

The HSJ commission set out to produce some practically useful tools to help the NHS improve hospital care for frail older people. Our scoping report was about supporting hospitals’ self-diagnosis; our main report set out key actions and best practice for hospital and system leaders, as well as highlighting a need to reset some expectations.

Our final report addresses the public and politicians on key areas that they as individuals should consider, offering some questions they can ask themselves to help with that thought process.

Reviewing the hospital and care landscape for frail older people, we observed three key impediments to improvement:

- money;

- regulation; and

- confusion over whether the system is planned or choice-based.

Our questions for politicians and citizens summarise key areas that link to frail older people’s hospital care. We also offer providers areas in which to review their progress.

Older people living with frailty, dementia or complex multiple co-morbidities are now “core business” for health and social care in all settings:

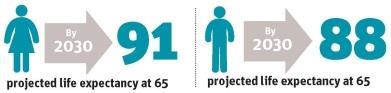

- People aged 65 in England can already expect to live two more decades. By 2030, projected life expectancy at 65 will be 88 for men and 91 for women.

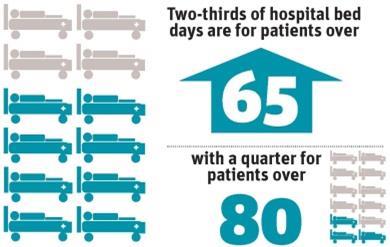

- Two-thirds of hospital bed days are for patients over 65, with a quarter for over 80s

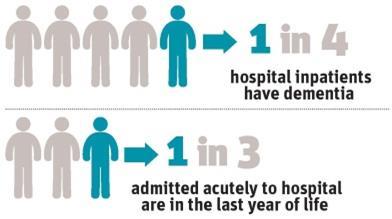

- One in four hospital inpatients have dementia.

- The average age of a user of intermediate care services is 83; the average age of a nursing home resident is 82.

- Most people receiving statutory social care at home are older people with complex needs.

- Primary care activity, spend and prescribing are dominated by people with one or more long term conditions – and most people over 75 live with at least three.

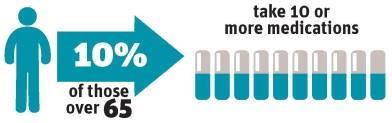

- 10 per cent of people over 65 take 10 or more medications.

- 1 in 3 adults admitted acutely to hospital are in the last year of their life.

- People over 85 account for proportionately the highest spend of all groups; across all services, the biggest proportion of spend goes on those over 65.

With increasing age, people are more likely to be readmitted to hospital within a month; experience delayed transfers of care; and have multiple contacts with multiple services, and poorly coordinated care at service interfaces.

Measuring obvious demographic and demand changes with ‘the Nicholson’ unit

Although these demographic and demand changes have been coming the NHS’s way for decades, we still seem oddly surprised by rising demand for care from our longer-lived frail older fellow citizens.

The NHS needs a new unit of measurement for the hugely obvious: we suggest that the unit of measurement should be “the Nicholson” – a tribute to NHS England’s inaugural chief executive Sir David Nicholson’s observation that the Lansley NHS reforms required “such a big change management, you could probably see it from space”.

Without sustained focus on improving our older people’s care, we cannot hope to solve pressing challenges of rising demand, ageing demography and social care cuts, nor address reports of poor quality, safety and avoidable harms. Many recent scandals around unsafe or undignified health and social care largely concerned our oldest citizens.

As we age, we use healthcare more. So we need good systems in place to help people age well, and to manage their own care where this is what they want and are able to do. We must avoid stigmatising frail older people who do need acute care, or who feel unsafe about being discharged. Their needs are real: we would do better to address our attention to the systemic failures to meet these needs.

‘Professor Nick Bosanquet said that the tariff has been “like using a nut to crack a sledgehammer”’

Of course, many people report high levels of happiness, wellbeing, health and social connection as they get older. Evidence suggests that those over 65 are becoming healthier and living longer in good health. There is plenty we can and should do around delaying or preventing illness.

There are many examples of good to great practice in services for older people across the NHS, highlighted in our main report.

The growing recognition of the need for more collaborative working and integration, new models of care as set out in the NHS Five Year Forward View, and for a greater focus on previously neglected syndromes such as frailty and dementia is welcome.

Professional leadership (such as the Royal College of Physicians’ Future Hospitals Commission; the British Geriatrics Society’s Fit for frailty and care home commissioning guidance; the National Gold Standards Framework Centre in End of Life Care; and the Royal College of Nursing work on care for older people) is helping to drive change. There are also notable successes from the voluntary sector – for instance Age UK, British Red Cross and the Royal Voluntary Service.

Few problems are so intractable that someone, somewhere has not solved them. The reliable spread of evidence-based good practice remains something we are yet fully to crack in the NHS and care systems, but this final report aims to offer fresh questions for organisations and individuals to use.

During the work of the HSJ commission, we have been struck by three broad areas where we need improvements to unblock problems with frail older patients’ pathways into, through and out of hospital.

Nine examples of penny-wise pound-foolish duplicative waste in care

Separation of health and social care budgets leads to economies in one piling on costs in the other. Examples include:

- Cost saving of removal of a handyman function in social care or community services, leading to extended lengths of stay in acute hospital awaiting adaptations.

- Social services’ level of funding often falls short of that required by a nursing home, which may require a top-up fee of, say, £200 per week. If this is not agreed, the patient spends many more weeks in hospital at a cost of thousands of pounds extra.

- Short staffing in social work (for a variety of reasons) means extended delays in getting assessments, leaving patients waiting in hospitals.

- Patients remaining in high-cost acute hospital beds due to housing issues when the cost of hotel accommodation would be cheaper.

- Reducing reablement/community service packages, resulting in longer length of stays in acute hospitals, which then reduces the likelihood of a patient living independently in his or her own home.

- Patient assessments undertaken by each agency or nursing/residential home. No single trusted assessor for the system that would be more cost-effective and reduce hospital length of stay.

- Unresponsive system for agreeing patient funding for out-of-hospital care can result in a longer length of stay in hospital.

- Reduction in access to funding for specialist equipment/home adaptations leading to an extended length of stay.

- Lack of responsive patient tracking systems for hospital patients requiring social care support results in longer length of stay in hospital.

Impediment 1: Money

The first area is financial. The tariff has several unintended consequences, among the most serious of which is a failure to reward hospitals’ A&E activity over the 2008-09 level due to the marginal tariff, as recently highlighted by the Public Accounts Committee’s report on NHS finances.

To help evolve more appropriate payment systems, we should remember that the tariff was made for the NHS, rather than vice versa. Health economist Professor Nick Bosanquet’s dry line that the tariff has been “like using a nut to crack a sledgehammer” raises a wry smile of recognition, but we will need payment reforms to avoid perverse incentives. We must also recognise that to transform care, we will need to look beyond the organisational silo and consider the health economy-wide picture, as the following two points describe.

Impediment 2: Systems, structures and cultures

The second impediment is covered by the broad heading “systems, structures and cultures”. It includes dysfunctions in the NHS leadership and regulation system, whose multipolar leadership includes what some hospital providers experience as regulatory overkill (and others as a regulatory Death Star).

Fragmentation is a big part of this problem. System leaders are trying to regulate organisations as standalone bodies. Today, it is increasingly clear that the success of any individual part of a health and care economy depends on all the other parts.

A fragmented NHS system causes problems at organisational and whole-system levels. Information sharing between agencies is poor; there is no single, transportable, universally accessible set of records. Often, there is no one person to coordinate care and navigate systems.

A basic checklist for better care provision for frail older people

- A workforce skilled in both health and social care that recognises the specific needs of older people, values them as individuals, involves them in care and relates to them in a compassionate way. Older people in hospital need to be supported to manage transitions, improve their health and be guided to a good end of life, where appropriate, in a place of their choice.

- A health and care system with a serious, sustained emphasis on healthy ageing, exercise and prevention to address the determinants of need.

- Primary and community clinicians who are equipped to assess and manage older people with multiple long term conditions properly, in longer consultations which include meaningful care planning.

- “Rapid response at home” services for frail older people, in which “first responders” would work with ambulance trusts to see if the older person can be treated safely and successfully at home (including care homes

- Care planning decisions that are taken very early, and by senior clinicians, when older people require hospital treatment. This minimises ward moves and leads to the right treatment by the right professionals with no delays and timely discharge.

While the focus on it in the Royal College of General Practitioners/NHS England coalition for collaborative care is a start, care planning is in its infancy, and often used only for a fraction of the over-65 population. Even when a care plan is in place, without capacity in a full range of services to support the person to remain at home or leave hospital sooner, they will still default into acute settings.

The National Audit of Intermediate Care 2014[1] starkly illustrated the lack of access and responsiveness in services outside hospital.

- Social care funding cuts mean around 800,000 people with care needs classified as substantial have been left without statutory support.

- More hope and pressure are being heaped on a primary care workforce which only receives 9 per cent of the NHS budget, and which is losing experienced GPs and nurses fast.

- Less than 1 per cent of the whole NHS budget goes on out-of-hours general practice.

Different accountabilities, regulatory mechanisms, IT and financial instruments for different organisations actively foster fragmentation rather than the “person-centred coordinated care” we crave.

NHS England’s Five Year Forward View offers two new models of care: the multidisciplinary care provider and the primary and acute care system. The vision is permissive, but the mechanism for achieving change remains opaque.

Proposals to deliver more care closer to home and increase the supply of clinicians with expertise in older people’s care interface needs seem sensible and welcome: the unanswered question remains “how?”. There is very little clarity on how we will get an adequately trained workforce located in the right part of the system to deliver this vision.

Despite the problem of rising urgent activity, dwindling hospital bed base and insufficient investment in prevention and in community alternatives to hospital - first described by the Audit Commission in 1997 and 2000 – urgent activity has continued to rise both in A&E and in acute bedded facilities, with hospitals running close to capacity.

Efforts to shift care closer to home have foundered on this lack of alternative investment. They have been compounded by social care funding cuts and lower proportionate funding for primary and community services. Instruments such as the marginal tariff for urgent activity or partial payments for readmissions demonstrably failed to create extra capacity.

The fixation with A&E four-hour performance misses the key point that acute bed occupancy and flow are largely governed by demand and capacity outside the hospital, as well as by public expectation and behaviour. Only one-third of over 75s admitted acutely to hospital (even with conditions usually managed in primary care) have been referred by the GP[2].

Care should be centred on the needs of the patient, rather than on the routines of the provider. Are we doing this?

Examples of good practice

- Ashford and St Peter’s Hospitals Foundation Trust Older person’s assessment and liaison services work with care homes to reduce admissions

- Poole Hospital Foundation Trust Rapid access consultant evaluation unit

- Sheffield Teaching Hospital Foundation Trust Experience of the ‘Flow Cost Quality’ improvement programme

- Abingdon Community Hospital/Oxford Health Foundation Trust Community-based emergency medical unit service in Oxford

- University Hospitals Birmingham Foundation Trust Work on dignity in care for inpatients, including for those with dementia

Impediment 3: Cake AND eat it - is our system planned, or choice-based?

The area of expectations and choice is also a problem. When the NHS had real-terms 6 per cent year-on-year cash growth, choice was used with the tariff to reward high performing providers who adopted best practice and reduced unnecessary overnight hospital stays for elective care. It is not always obvious that reforms to payment systems are well aligned with incentives for providers to do the right thing.

The philosophy underlining choice’s role in the system also matters. User and carer involvement in care has two different historical legacies: one driven by human rights and civil liberties and the other by bureaucratic cost effectiveness and economic stringency[3]. In offering choice, health professionals can feel conflicted about the underpinning reasons it is being offered.

‘Hospitals are full, important and popular’

Evidence suggests that professionals may view choice more positively when it is linked to humanistic thinking, yet they may fear that lay participation in care is being imposed for economic reasons[4].

We must encourage professionals to be more open and honest with the public about whether real choice is possible – and, if it is not, the underpinning rationale for this. If choice is more available in wealthier and more populous areas (and less so in less wealthy and less populous ones), we should acknowledge this, and not expect professionals to deliver things that they can’t.

If what we are willing to fund is a planned system - as opposed to a choice system with appropriate extra capacity to make the choice a reality – we need to be candid and consistent, internally and externally, about the reasons why this is the choice we have made.

Hospitals are full, important and popular. Asking them to deliver more care for frail older people for less risks triggering the classic builder’s conundrum of “on time, well built, or cheap: pick any two out of three”. It may have a negative impact on quality, especially when trained consultants in geriatric medicine are in short supply.

True perspective, forced perspective

To improve hospital care for frail older people, we need a true perspective of how good our current provision is. We need just as accurate a perspective on what good care looks like, as the main report highlighted. And we need hope that hospital providers can share learning and improve their services to compare with the best.

The hope is as important as the perspective. In the artist MC Escher’s famous lithograph image Ascending And Descending, a group of people appears to be trapped on an ever-ascending staircase. At times, the demand on hospitals from frail older people may well feel like a Sisyphean task of this kind.

The physics of the Escher image are clearly impossible: the artist tricks the viewer, using forced perspective. To improve hospital care for frail older people means we need a clear, fresh and unforced perspective. To help develop this, our final report concludes with some questions (see right).

References

- The National Audit of Intermediate Care 2014, November 2014, NHS Benchmarking Network

- Thomas E Cowling, Michael A Soljak, Derek Bell and Azeem Majeed (2014) “Emergency hospital admissions via accident and emergency departments in England: time trend, conceptual framework and policy implications”, Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine, November 2014 107: 432-438

- Van den Heuval WJA (1980) “The role of consumer in health policy”, Social Science and Medicine, 14A, 423-426.

- Meyer J (1995) Lay Participation in Care in a Hospital Setting: An Action Research Study, unpublished PhD thesis, King’s College London, University of London

Downloads

Hsj frail older commission final report 150320

PDF, Size 0.76 mb

HSJ commission final report: Are you doing enough for frail older people?

Putting questions to politicians, citizens and providers

Currently

reading

Currently

reading

HSJ commission final report: Are you doing enough for frail older people?

- 2

No comments yet