Every day people who are in hospital against their wishes die. But evidence shows community-based services can improve the quality of end of life care, writes David Shaw

Earlier this year, the Office for National Statistics released results of the VOICES survey of bereaved people. It was the first time bereaved relatives across England were surveyed to gauge the quality of care received at the end of their loved one’s life.

One finding was particularly striking: only 29 per cent of people who died in hospital were said to have had enough choice about where they died. Compared to 53 per cent of those who died in a care home, 70 per cent of those who died in a hospice and 88 per cent of those who died at home.

‘Emergency admissions can be a stressful experience and often come with clinical and psychological risks’

The survey confirmed that terminally ill people would rarely want to die in a hospital and that many people’s experience of end of life care in hospital is poor. Yet annual mortality statistics show that over half of deaths occur in hospital, with some areas seeing hospital death rates as high as 69 per cent.

Unnecessary admissions

Hospital care costs in the last year of life equate to an average of £6,644 per person. If we took this as an appropriate crude average cost nationally, this would represent total final year hospital care costs of £3.7bn.

Across England, people make an average of around two hospital admissions in the last 12 months of life, accounting for an average of 30 bed days. Many of these admissions are unplanned: 346,000 people have an emergency admission, which accounts for around 9.4 million bed days.

However, the King’s Fund estimates that in England more than 30 per cent of older patients, admitted as a medical emergency, do not actually need to occupy a hospital bed.

Aside from being extremely costly to the NHS, emergency admissions can be a stressful experience for the patient and carer, and often come with increased clinical and psychological risks.

Crucially, the high proportion of hospital admissions experienced at the end of life does not match up to people’s preferences about place of death. Sixty-three per cent of the general public in England would prefer to die at home. This preference is also echoed by the dying, as revealed in the VOICES survey.

Need for alternatives

With budgets already stretched, it seems unlikely that current models of care will be able to stand up to the 17 per cent rise in the number of deaths in any one year from 2012 to 2030, as is forecast.

It has been estimated the price of an inpatient admission in the last year of life that ends in death ranges from £2,352-£3,779.

The mid-point of this estimate is almost £1,000 higher than the mid-point of the estimate for care in the community, therefore there are potential cost savings to be made by supporting community alternatives for end of life care.

In short, patient experience, patient preference and financial factors all point to the need to promote alternatives to hospital care at the end of life.

Marie Curie impact

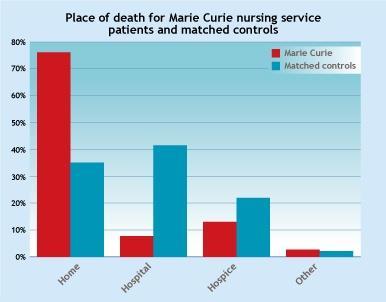

On November 14, the Nuffield Trust released a study that examined the hospital use and place of death of over 30,000 patients who had used the Marie Curie nursing service. It then compared these outcomes to 30,000 individually matched controls that were similar in all respects, other than not being Marie Curie patients.

This was the first large-scale England-wide study that has used matched controls, thereby providing much more robust evidence of the impact of community nursing at the end of life than was previously available.

Findings demonstrate that the Marie Curie nursing service enables more people to die at home and reduces hospital admissions and costs. Its patients were twice as likely to die at home as matched controls.

‘Effective case management and coordination is essential to ensure services are there when people need them most’

The rate of emergency admissions and accident and emergency attendances for Marie Curie patients was found to be around one third of the rate for matched controls. It is well documented that there are significant barriers to accessing palliative care for people with non-cancer conditions, as highlighted in a report for Hospice Care Week in October.

The Nuffield Trust study shows that delivering good community end of life care services to this group has a significant impact on their outcomes. The impact on hospital use was even more marked in the 23 per cent of Marie Curie patients who do not have cancer than they were in those with a cancer diagnosis. This underlines the importance of ensuring that services broaden access to patients with all conditions.

Designing useful services

Both the Nuffield Trust study of the Marie Curie nursing service and evaluations of the Marie Curie delivering choice programme sites in England demonstrate the benefits of community-based care strategies.

Marie Curie’s programme helps local providers and commissioners to develop a range of coordinated local services for palliative care patients, regardless of diagnosis, which have patient choice at their heart. For example, services that provide round-the-clock crisis care.

Effective case management and coordination is also essential to ensure services are there when patients and carers need them most.

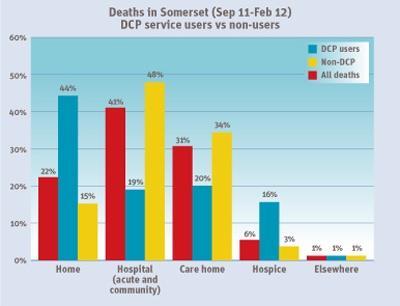

The success of the choice programe in Somerset is testimony to this holistic approach. With a higher than average number of over-65s and a rural setting, Somerset provided a variety of challenges.

‘If care for people at the end of life really is to be improved, we must channel our resources in a focused and efficient way’

The project used a whole systems approach to develop integrated end of life services and bring together providers and commissioners from the public, independent and voluntary sectors. A number of initiatives were introduced, including a coordination centre to arrange home care packages, an out-of-hours response line and discharge nurses.

A recent independent evaluation of the programme in Somerset by University of Bristol concluded that emergency admissions in the last months of life in Somerset were 39 per cent lower for users of the programme than for non-users. In addition, A&E attendances were 34 per cent lower in the last months of life.

Tools for the job

If care for people at the end of life really is to be improved, then we must ensure we channel our resources in a focused and efficient way, recognising that local health economies have individual and differing needs.

The guidance from National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence on commissioning end of life care for adults recommends that commissioners and their partners conduct a local needs assessment. They should estimate local service need, to plan capacity and improve the accessibility and inclusivity of local services.

With this in mind, Marie Curie has developed the UK End of Life Care Atlas, a web-based mapping tool that brings together a broad range of data on end of life care across the health landscape. It supports commissioners by providing insight into their populations, highlighting where need is greatest, how need varies and where additional services would have the greatest impact on the lives of patients and families.

Evidently hospital care should not be sidelined. Hospital can be the most appropriate place of care for a patient and the preferred place of care in some cases. Nevertheless, every day people continue to die in hospital against their wishes. The evidence shows we can achieve real quality and productivity gains − our job is to make that happen.

David Shaw is head of service development at Marie Curie Cancer Care, david.shaw@mariecurie.org.uk

No comments yet