Emma Stanton, Brain Wheelan and Thishi Surendranathan review the success of Improving Access to Psychological Therapies, a flagship programme to get people into mental health treatment

The Adult Psychiatry and Morbidity Survey 2007 estimated that more than one sixth of the UK population suffered from a common mental health disorder. The Improving Access to Psychological Therapies programme is a national initiative aimed at improving access to routine evidence-based treatments for people with common mental disorders such as anxiety and depression.

‘Further scope for improved productivity lies in technological innovations, including mobile apps’

In his Depression Report, Professor Richard Layard of London School of Economics outlined how comprehensive access to psychological therapies could produce significant direct benefits to patients’ mental health and indirect benefits to their physical health.

According to the report, the total cost to the economy, in terms of loss of output, was estimated to be £12bn, of which £7bn was borne by the taxpayer; the estimated cost of psychological therapies service was £0.6bn.

After two successful pilot services in Newham and Doncaster that demonstrated impressive recovery rates (approximately 50 per cent of those treated) and a second phase of rollout to pathfinder sites, further waves of IAPT culminated in a Department of Health plan to complete nationwide rollout backed by a government investment of £400m for the four years from April 2011.

Main objectives

As a flagship mental health initiative that has received attention at the highest level of government, IAPT is well funded and publicised. It is also a service that makes significant use of data with nationally set key performance indicators for performance management, benchmarking and to achieve the national IAPT programme objectives.

In 2012, Beacon UK, a mental healthcare provider, analysed the indicators data submitted by existing IAPT services across England for 2011-12 in order to benchmark current IAPT service performance and identify arising challenges.

Our analysis revealed the following:

- 533,550 people accessed IAPT services, reaching only 8.7 per cent of people suffering from anxiety and depression disorders.

- Four out of 31 (13 per cent) IAPT services in London and 37 out of 151 (25 per cent) services in England achieved the national target of a 50 per cent recovery rate.

- 96,770 (11 per cent) people waited more than 28 days from referral to first treatment session.

- 22,498 (6.8 per cent) people no longer required sick pay or benefits following a course of treatment.

- 60.1 per cent of referrals to IAPT entered treatment. The highest acceptance rate was at Calderdale (99.7 per cent); the lowest acceptance rate was Telford and Wrekin (28.9 per cent).

We have identified three challenges for commissioners and providers of IAPT services to achieve the national objectives.

Objectives for the full rollout of IAPT in England in 2011-2015 include:

- 3.2 million people will have accessed IAPT, ie 15 per cent per annum of those suffering from depression and anxiety.

- 2.6 million will have completed a course of treatment (two or more sessions).

- 50 per cent of those completing treatment (1.3 million) will move to measurable recovery.

- 75,000 people should have gained or kept a job, education, training or volunteering placement.

- Universal, equitable access will have been achieved, especially for ethnic minorities and people over 65.

- Extending services to include people with long-term physical conditions, medically unexplained symptoms, severe mental illness and a standalone programme for children and young people.

Measuring the value of IAPT

Distinct funding and objectives have incentivised commissioners to consider IAPT as a separate and distinct entity rather than to integrate it into the pre-existing healthcare economy. For example, the absence of a strong relationship with the local community mental health team risks people “falling through the cracks”.

The outcomes data is not without flaws. IAPT services treating more severely ill people may see greater improvement in questionnaire scores but demonstrate lower recovery rates, for example. This is because overall scores are less likely to dip past the defined threshold for recovery.

Looking ahead, the definition of recovery in IAPT seems likely to change to a set level of improvement in a questionnaire score rather than achieving a threshold.

Outcomes measurement for IAPT could be improved by risk adjustment to take into account local areas’ and individual patients’ needs. In addition, condition-specific measures and individual, patient-defined recovery indicators could also be captured.

Improved value may also be achieved by deploying services earlier in the course of an illness − to prevent a deterioration requiring inpatient admission.

Defining the scope of IAPT

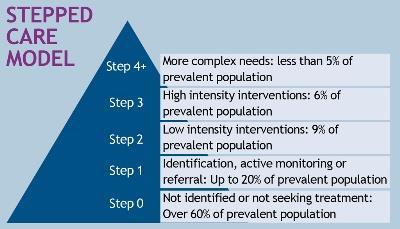

The initial goal for IAPT was to deliver short, targeted psychological interventions as per NICE guidelines for stepped care, focusing on low-intensity and high-intensity interventions (see figure 1). A common challenge facing IAPT services is the temptation to provide care to more complex patients outside of the defined scope of IAPT contracts.

[Figure 1: NICE stepped care model for people with common mental health disorders – with expected level of patients accessing services]

As shown above, step 4 is intended for people with more severe and complex mental health problems requiring higher intensity care, or for those requiring multidisciplinary team input but not meeting the referral threshold for secondary mental health services. Such people require more specialist care than is typically provided by the standard IAPT model.

Some commissioners have developed innovative approaches to providing care for people with more complex mental health problems, including:

- contracting a distinct “step 4 service” from the same provider, separately from IAPT;

- establishing a single point of access for a primary care-based federated model of mental health services, including IAPT, but extending to include other providers;

- and an independent assessment and referral service providing a single point of contact for all IAPT and substance misuse issues alongside the main mental health providers. Providers are reimbursed according to the outcomes achieved.

Improving access to IAPT

By 2015, the national access rate for people with a common mental disorder is expected to be 15 per cent. According to 2007’s Adult Psychiatry and Morbidity Survey, common mental disorders have a higher prevalence in the North East (26 per cent of women and 11.6 per cent of men), while the lowest prevalence was in South Central (18.6 per cent of women and 8.4 per cent of men).

Overall, there was a higher prevalence of mental health problems in black and other ethnic groups than in white and South Asian groups. In addition, divorced people and people from with lower household incomes were also more likely to suffer from common mental disorders.

To improve access rates for different high-risk groups, IAPT services need to be marketed differently.

Self-referral appears to be a more equitable way of improving access for those who are unlikely to visit their GP, such as some ethnic minorities. Working with third sector organisations who help ethnic minorities with mental health problems to provide language-specific psychotherapy services may be another way to enhance access.

Employing “star workers’’ is another approach to target higher risk groups, including those in employment offices and those whose houses have been repossessed. Health trainers are also a source of referral. Delivering services through community centres close to patients’ homes reduces the stigma of accessing mental health services.

Where next?

Isolated short psychological interventions via IAPT are an evidence-based approach for people with common mental disorders. While the short-term focus for commissioners is to improve access and recovery rates in line with national targets by 2014-15, the long-term strategy must be to better integrate IAPT services into the broader health and social care landscape. Integration is currently not captured by any of the national key performance targets.

Further scope for improved productivity lies in technological innovations, including mobile apps and secure email to facilitate patient-therapist communication.

Overall, the IAPT programme is likely to more than pay for itself through the improvement in the wellbeing of its service users and benefits to the wider economy.

Find out more

Dr Emma Stanton is an NHS psychiatrist and CEO at Beacon UK, Brian Wheelan is vice president for corporate development and strategy at Beacon Health Strategies and Dr Thishi Surendranathan is a senior analyst at Beacon UK.

1 Readers' comment