The political significance of waiting times is such that the NHS will have to hit the 18 week target and then hold it at least until the post-election spending review reveals whether the NHS will get the extra money it needs, say James Thompson and Richard Murray

In years gone by, the most common criticism of the NHS was its tolerance of long waiting times for patients. The historic reduction in waiting times achieved by 2008 – as enshrined in the 18-week maximum wait from referral by a GP to treatment – has in turn become an iconic measure of NHS performance for politicians and the public alike.

Fears the target would be broken led the health secretary to announce an extra £250m to buy more treatments and, ultimately, to ensure the waiting time target was under control by the end of the year. How likely is this to happen?

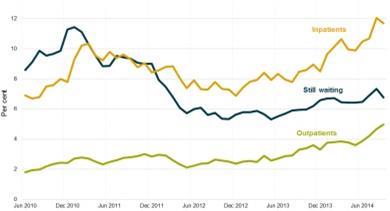

All good targets need to be defined clearly. The 18 week target is made up of three linked standards: 90 per cent for patients whose treatment requires admission to hospital; 95 per cent for patients whose treatment is undertaken in outpatients (the non-admitted standard); and 92 per cent for patients still waiting to begin treatment, as an outpatient or for admission to hospital.

‘After a rather dismal summer, the numbers in September did at least go (largely) in the right direction’

By June, when the £250m was first announced, the admitted patient standard had already been breached (just) in February and March. The number waiting significantly longer (more than 26 weeks) had also been rising, as had the total number of people on waiting lists. To combat this, the £250m given to clinical commissioning groups (CCGs) was meant to buy more treatments from hospitals in July and August. This activity was to be over and above their normal monthly workload.

The final twist came in August, when Jeremy Hunt announced a “managed breach” of the admitted patient standard to allow the NHS to focus on reducing the numbers who had waited the longest. When June’s numbers were published soon after this, they confirmed that the NHS had again breached the admitted patient standard and has continued to do so.

So where are we now?

The plan was that the extra work done in July and August to deliver the target would be visible in September’s performance. Data for September has just been released and clearly this did not happen – the admitted patient standard sits at 88.3 per cent, still shy of the required 90 per cent.

Indeed, NHS performance in general continued to decline through July and August, as shown in the graph below. Fortunately for the NHS, the managed breach announcement from Mr Hunt had already reset the deadline for delivery of all three standards back to the end of 2014.

After a rather dismal summer, the numbers in September did at least go (largely) in the right direction, although not by enough to hit the standard. Performance improved for admitted patients and for the numbers still waiting. There were also falls in long waits (more than 26 weeks) as well as in the total size of the waiting list – although this remains at 2.99m patients, rising to an estimated 3.2m if non-reporting trusts submitted data.

Per cent of patients still waiting/having waited more than 18 weeks for treatment

Will performance be back on track by the end of the year?

Clearly the NHS still has some way to go, and commentators will be scrutinising each month’s data to see if the NHS can continue and accelerate the downward trajectory it finally achieved in September. We will return to this in the new year to see whether the standards are delivered within the timeframe set by Mr Hunt.

In the meantime, there are two immediate concerns.

First, the non-admitted standard has continued to deteriorate into September. Historically the easiest of the standards to hit it is still, at 95.2 per cent, only a fraction above the 95 per cent required.

‘Performance on waiting times will inevitably be part of the general election debate’

Second, the unusually warm weather in autumn has finally stopped, reminding us that winter is coming. This is a time when focus in the NHS usually switches to intensive management of A&E and, as we all know, the A&E waiting times target has also had a very difficult year.

We are therefore entering winter with the traditional concerns over emergency care while at the same time pushing to get 18 week waiting times back on track.

Looking slightly further ahead, meeting the standard in December is, of course, only part of the challenge. The political significance of waiting times is such that performance on waiting will inevitably be part of the general election debate – the NHS will have to hit the target and then hold it, at least until the post-election spending review reveals whether the NHS will get the extra money it needs.

James Thompson is a senior research analysts and Richard Murray is director of policy at the King’s Fund. This article also appears on the King’s Fund blog

3 Readers' comments