The barriers and challenges in cancer care need to be explored locally, regionally, and nationally – and dismantled, writes Laura Fulcher

Now that the most devastating stage of the pandemic is (hopefully) behind us, the new recovery plan to support those waiting for treatment was announced last week. While these plans may help people already waiting in the system, they bring scant hope for the 740,000 people who may have missed cancer referrals during the pandemic. Little is being done for those unable to access and navigate healthcare - and there is a very limited plan to prevent the thousands of cancer deaths that could ensue.

The plan’s best offering for these people was to battle on with the current ‘Help us to help you’ awareness campaign, which aims to persuade people to seek help. Meanwhile, strategists wonder, ‘we still don’t know how long people will delay seeking the treatment they need,’ – as if these delays are all in the hands of patients.

As someone who faced a 15-month cancer diagnosis delay (after 9 GP appointments and 5 procedures for a pretty run of the mill bowel cancer), I know it’s more complicated than delays being solely caused by patients. I run Mission Remission, a grassroot cancer charity, and what my community needs is proper person-centred action. Every month cancer treatment is delayed raises the risk of death by 10 per cent (British Medical Journal).

Where the UK first goes wrong with cancer diagnosis is by resting its entire public-facing approach on just two steps. We tell people: 1. Look out for cancer signs; 2. Go see a GP straightaway who will refer you for urgent tests, where needed.

And we continue with this approach knowing that it just doesn’t help people. Public Health England research found less than 50 per cent of those who have cancer are ever referred along the urgent pathway for tests.

The recovery plan makes the same fatal error: working on the premise that to speed up cancer diagnosis, all you need to do is improve the urgent pathway. Focusing on the minority of ‘urgent’ referral cases does nothing to support the majority of us with cancer.

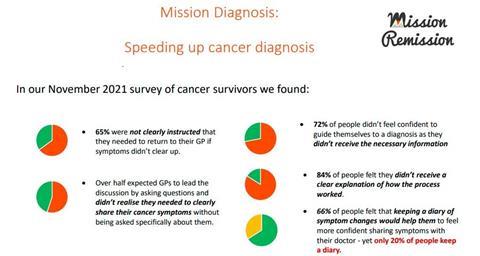

Mission Remission conducted surveys and workshops with over 350 cancer survivors last year, drilling down to what could really speed up the process for people. We found a dispiriting lack of information and support for people in the early days of diagnosis:

- 65 per cent were not clearly instructed that they needed to return to their GP if symptoms didn’t clear up.

- 66 per cent of people felt that keeping a diary of symptom changes would help them to feel more confident sharing symptoms with their doctor - yet only 20 per cent keep a diary.

- Over 50 per cent expected GPs to lead the discussion by asking questions and didn’t realise they needed to clearly share their cancer symptoms without being asked specifically about them.

- 72 per cent of people didn’t feel confident to guide themselves to a diagnosis as they didn’t receive the necessary information

- 84 per cent of people felt they didn’t receive a clear explanation of how the process worked.

While international comparisons explain our poorer cancer outcomes by pointing the finger at UK citizens – we’re healthcare avoidant and reluctant to bother clinicians – what is the health service actually doing to address this? Where is the help for people communicating with and navigating an often confusing system?

Public Health England research found less than 50 per cent of those who have cancer are ever referred along the urgent pathway for tests. The recovery plan makes the same fatal error: working on the premise that to speed up cancer diagnosis, all you need to do is improve the urgent pathway

Looking at the Faster Diagnosis Standard, it provides a good example of how disempowering health strategy really is – it has little awareness of the patients’ role and the importance of supporting health-seeking behaviour. What might a more person-centred Faster Diagnosis Standard look like?

First, to be person-centred is to care for all patients, not just the minority privileged to be referred urgently (surely the first step for anyone who cares about reducing healthcare inequalities?) Cancer diagnosis targets need to be grounded in what matters to people: being diagnosed and treated from the first signs we’re sick, not from 28 days after an arbitrary point of referral – which I have often found to be a moveable date depending on who you speak to.

A person-centred approach would prioritise patient knowledge and proactive behaviour. Every GP appointment needs to end with ‘next step discussions’, ie talking about when we return if symptoms don’t clear up and what to do if our condition worsens. There needs to be a system of escalation when people do return, perhaps a primary care diagnosis pathway. We must stop treating GP appointments as one-off interactions – even if we see a locum or new GP – so that cancer is ruled out at the earliest step.

Meanwhile, for all those GPs being trained to be more person-focused and taking the lead from patients on what they want, people are often unsure of what they can actually ask for. They don’t know they can ask for tests and aren’t clear on when they can ask to be referred to a specialist. There is no guide to diagnosis that explains the process.

When the NHS was first founded, every single household received a letter explaining how the system worked and what services were available. We need a new guide providing information on access and explaining how to navigate healthcare in the post-covid world.

Most importantly, people need help with navigating the current barriers. At Mission Remission, we’ve worked with our community to build a list of potential barriers to diagnosis so we can help people overcome them.

Barriers come in many forms, such as over-zealous receptionists trying to protect their exhausted GPs; an overwhelmed PALS not acting on calls; difficulties building a trusting relationship with a new GP after a past negative experience; or finding confidence to share cancer worries – for many, a lack of confidence can be enough of a barrier to seeking help. People need an advocacy service to help them with this – run by those who have already been through the system; people who can help inspire and motivate them to take the first step.

These barriers and challenges need to be explored locally, regionally, and nationally – and dismantled. It isn’t good enough just to wonder when people will seek help.

In the absence of a grand overhaul of services, such as sharing power with patients by allowing people direct access to secondary care specialists, we must instead address the power imbalance during GP interactions. Help people by providing the tools – such as our symptom diary – to articulate worries clearly and find the confidence to speak up.

Lastly, we need to think creatively about the relationship between people and their GPs – relationships that have taken a big hit in the pandemic. With the halcyon days of the family GP long-lost; what does a supportive GP relationship look like now?

These person-focused aims should be integral to our health service – and yet it is difficult to find anyone responsible for making these kinds of changes happen. When I appeal to the NHS, NHS England points Mission Remission to the Cancer Alliances; yet most Cancer Alliances aren’t in a position to engage on patient-focused agendas with so much else going on.

It leaves me with the hopeless feeling that we are marching in our sleep towards hundreds of thousands of cancer deaths – and the obscene terror that most of the country is totally unprepared.

No comments yet