Increasingly integrated care challenges the current role of small hospitals, but the pandemic has revealed a powerful new role for these traditional institutions, say Ben Horner, Laura Bergonzini, Stephen Sutherland and Robert Marshall

Sponsored by

From UK’s city centres to the outback of Australia, small hospitals face a series of existential challenges. Many have retained the same care model they have followed for decades, even as workloads and average patient acuity continue to increase. Some, especially those in urban areas, are being squeezed on one side by larger academic hospitals and elective hubs, and by a trend toward increased care in the community on the other. And all must find a way to fit into health care systems that are becoming ever more consolidated. Despite these challenges, we believe that small hospitals have an increasingly pivotal role to play in healthcare systems around the world.

The rise of Integrated Care Systems

The “District General Hospital” formally emerged in the 1960s as the “backbone” of the NHS, focusing on providing care to local populations, offering core general services such as maternity care and paediatrics, elderly care, emergency care, and simple elective care. Their role expanded over time as other types of community beds disappeared.

Ben Horner

Ben Horner

Now, however, we are in a new phase—one characterised by increased specialisation and integration at a system level. Large tertiary hospitals often exert a strong gravitational force, pulling patients away from small hospitals. Small hospitals must innovate and find their new role within these new systems.

The role of small hospitals within health systems

Stephen Sutherland

Stephen Sutherland

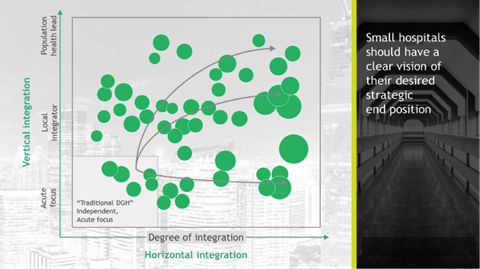

Small hospitals’ current role of delivering “a little bit of everything” is becoming more and more unsustainable as they can’t fully deliver to their population as they lack the scale to deliver the specialised care that is increasingly required. Possible futures for small hospitals can be viewed through two dimensions:

Vertical integration: Given that primary and community care is still relatively fragmented, small hospitals can have a leading role in vertical integration at both a place and system level. Adopting this role would help reduce unwarranted variation, and lead to the improvement of common community/acute interfaces for rapid response, discharge pathways, community (virtual) bed models, diagnostics, and preventative care (eg, MSK, Diabetes).

Horizontal collaboration: Small hospitals also need to partner with other hospitals to gain the benefits of scale: Joint corporate and clinical support services are well-proven models and can be implemented relatively quickly. Clinical-pathway development also offers significant opportunities and can quickly build from existing clinical networks through agreed protocols and joint appointments.

In the UK, there are several examples of hospitals pursuing both vertical and horizontal integration. Whittington Health, an Integrated Care Organisation in London, runs local community and children’s mental health services that are closely coordinated with social care, while providing approximately 200 inpatient acute beds and 400 virtual beds; it is also pursuing stronger horizontal integration by moving its orthopaedics care to an ICS hub. These shifts are being enabled by increased use of telemedicine, which has strengthened access for many such as elderly people, or people with long-term conditions.

Laura Bergonzini

Laura Bergonzini

The same dynamic is true in rural settings. Central West Health in rural northeast Australia has small local sites that deliver core acute and generalist services. But it also provides access to more advanced care, either by transferring patients through well-defined care escalation pathways or by bringing specialised services into their hospital via telehealth. They have adopted digital tools to provide access to specialist care from larger hospitals in their network and live virtual specialist management of patients in the emergency department. Staff at rural sites also lead delivery of primary care and community services. In general, geographic necessity has forced these sites to find their own ways to deliver both acute specialist and integrated community needs to their remote populations.

A Time for Action

The disruption due to covid-19, with increased openness and collaboration, provides a window of opportunity to lay out a bold vision for small hospitals. Small hospitals have an important role to play in the future of healthcare delivery, and to be anchor institutes for their local communities. But they need a clear vision of their future role, and their role will differ by system. Only by understanding their place in relation to other services in the system, can they deliver care in a way that satisfies their local population, and delivers value.

Robert Marshall

Robert Marshall

Boldness of vision must be accompanied by boldness of action, both by the small hospitals and by the system as a whole: small hospitals cannot innovate in isolation, but their vision can become a crucial component to improve patient care. At a system level, two main actions follow from what we have discussed so far:

New Builds: At national and ICS level, we need to re-think the role of small hospitals within their system. Rather than designing around unsustainable legacy models of care, we need to design and build hospitals that can deliver that vision.

Financial Incentives: we should create incentives that support new models for small hospitals based on an understanding of whole-system costs, and encouraging ongoing innovation

Small hospitals should take the lead in re-thinking their portfolio, and start delivering on their vision, taking some actions such as:

Virtual Care: With their local knowledge of services available and of the patients’ context, smaller hospitals are often able to deliver better care closer to home enabled by new digital, data and analytics technology

Adaptive Workforce: Break with traditional models to create new hybrid staff roles, including non-medic-led care delivery. As covid-19 demonstrated for critical care staffing, this transition can happen quickly but requires Royal colleges and others to lead and enable it.

The covid-19 pandemic has disrupted care delivery and forced providers to work in new ways, some of which have proven to be beneficial. We must not forget the lessons we have learned during this crisis. Instead, we must seize the opportunity to reset key parts of the current care delivery system, recognizing that far from becoming irrelevant, small hospitals can be the engines driving the system toward more integrated care.

Ben Horner is a partner and managing director in the London office of The Boston Consulting Group, and leads their work with hospitals and health systems across UK, Netherlands and Belgium.

Stephen Sutherland is a partner in BCG’s London office and a core member of the Health Care practice.

Laura Bergonzini is an associate director in BCG’s London office and a core member of the Health Care practice

Robert Marshall is a project leader in BCG’s London office and a core member of the Health Care practice