As the prime minister prepares to launch the pilots of the ‘access challenge fund’ it is important to be wary of ‘supply induced demand’ and how it can change the primary care landscape. Rebecca Rosen breaks down the factors and looks to the future

Improving access to general practice and other primary care services is a key concern for policy makers and practitioners.

People are frustrated by difficulties contacting their GP surgery, long waits for appointments and the difficulty of seeing a doctor or nurse they know at a convenient time.

Both the Coalition government and the Labour Party have made better access to general practice a priority for reforming the NHS.

‘As services expand and become easier to use, will more people will attend with minor self-limiting conditions?’

Access points to primary care are changing.

Patients can access a GP through their registered practice, out of hours services and walk in centres. Assessment and advice is also available through NHS 111 and pharmacists with treatment for selected conditions available in minor injury units and urgent care centres.

But is there a risk that, as services expand and become easier to use, more people will attend with minor self-limiting conditions?

- Practices increasingly relying on primary care staff to fill GP shortfalls

- Twenty pilots selected for extended hours

- The NHS gets the A&E demand it deserves

- More commissioning news and best practice resources

- Sign up to HSJ’s commissioning newsletter to receive weekly emails

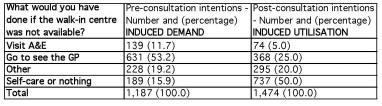

Induced demand and induced utilisation as a proportion of all contacts in six private, doctor staffed commuter walk-in centres

Source: Nicholl, 2014; adapted from Cathain and others, 2009

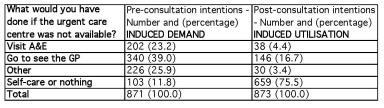

Induced demand and induced utilisation as a proportion of all contacts in two private, doctor staffed urgent care centres

Source: Nicholl, 2014

Supply induced demand

Jon Nicholl from Sheffield University found that for approximately 15 per cent of walk-in centre contacts, and 11 per cent of urgent care centre contacts, patients would not have used another service - induced demand - if the centre they used did not exist.

In addition, 30 per cent of walk-in centre patients and 21 per cent of urgent care centre patients were referred onto a service that they could have accessed anyway - induced utilisation.

‘Extra demand can be stimulated both by easier access to new forms of primary care’

The data was presented during a recent talk at the Nuffield Trust. This concept is known as “supply induced demand”.

Rooted in economic theory, it reflects the role of doctors as agents for patients, with the ability to shape their views about the services they want and need - supplier induced demand.

There is also evidence that geographic variations in the use of health services are linked to regional variations in their supply - supply induced demand.

More recent English research shows how extra demand can be stimulated both by easier access to new forms of primary care - induced demand - and primary care consultations which end with patients being referred to other services which they could have chosen to use in the first place - induced utilisation.

Examples of the prime minister’s access challenge fund

In October, prime minister David Cameron launched a £50m “challenge fund” to pilot a selection of 20 schemes designed to improve access to general practice and primary care. The services will be launched later this year. Some examples of pilot schemes include:

- Extended clinic hours organised through networks of GPs serving defined patient populations in centralised clinics - opening hours vary between sites.

- Access to GP services for non-registered patients including those redirected from accident and emergency.

- Skype consultations for care home residents.

- Longer appointments and additional care coordination for patients with complex needs.

- Use of new technologies to broaden access routes to appointments including Skype consultations, emails and electronic consultation templates completed by patients, web chats, texted reminders and wellness messages.

- Use of computer signposting to primary care services such as pharmacy and physiotherapy.

- Use of different triage methods to guide patients to the service best suited to their needs, including GP telephone triage, voluntary sector care navigators and phone apps.

- Use of phone apps to carry messages to doctors, order prescriptions and book appointments.

Matching services to improve

The revised NHS constitution removed the 48 hour access target, but the language of patient choice and rights is still evident.

In an intensely cash strapped system, to what extent should we consider it an absolute right to have repeated rapid access to services often providing reassurance or responding to low levels of clinical need?

With limited resources, is there an argument to focus on timely access where diagnosis, treatment and continuity of care are most needed?

Clinically, these needs are hard to disentangle and both professionals and service users have a part to play in matching needs to service use as we work on improving access.

Checking – or re-checking – a common, self-limiting ailment because an immediate access service is available, can reassure, but can also erode confidence to self-care.

‘Re-checking a common, self-limiting ailment because an immediate access service is available, can reassure, but also erode confidence of self-care’

Increased service use due to greater availability or easier access to care can be a good thing. It can result in checking a long neglected symptom and early detection of an underlying illness.

Walk in facilities offer access to unregistered and homeless patients, and may be convenient for workers who cannot reach their registered doctor during working hours.

But there are potential downsides too. Checking – or re-checking – a common, self-limiting ailment because an immediate access service is available, can reassure, but also erode confidence of self-care.

Patients can move around different providers if they access a service which lacks the infrastructure or incentives to meet all their care needs in as few episodes as possible. And with growing concerns about shortages of GPs and community nurses, spreading the existing workforce over longer hours, and providing easier access for acute symptoms which are often self-limiting, could divert limited resources away from patients with complex health needs.

Existing innovations to guide the prime minister’s fund

Services already exist from which the “challenge fund” pilot sites can learn.

Blackpool, and Fylde and Wyre clinical commissioning groups have an unscheduled care strategy that is interwoven with routine services. They have common standards of care across different providers, and care pathways that steer patients to the most appropriate provider for their clinical problem.

A growing number of GP practices have now introduced telephone doctor triage for all their patients. Some claim this approach solves many issues associated with accessing general practice: allocating patients to the most appropriate clinician, determining how long an appointment is needed, and organising tests before seeing a clinician.

This kind of compulsory telephone triage is also seen in other health sectors. In Copenhagen, for example, it is only possible to attend A&E as a walk-in patient after preliminary telephone triage.

Technology is also playing a role in steering people to the right service. Phone apps exist to check symptoms and advise on self-management. Some practices offer e-consultations with options to find out about self-management or visit a pharmacist as alternatives to complete an online template to be reviewed later by a clinician.

The challenge of educating for the long term

Perhaps the most difficult challenge lies in changing patient behaviours and expectations about access to healthcare.

Education campaigns about choosing the “right service” receive a mixed press, and if they do work, they are often slow to take effect.

Many are short lived – part of a local winter pressures campaign – and typically rely on posters and leaflets, rather than wider, multichannelled campaigns. This may explain why their impact is limited.

‘It is tricky to meet demand without inducing extra demand that clog up expanded services’

Patient education could focus on building long term capacity for individuals, families and communities to cope with minor and early stage illness, reducing the demand for professional care.

Small pilot services have had some success in this area but there have been few attempts to scale up this approach.

As Mr Cameron’s “challenge fund” sites prepare to go live, they have a complex and difficult task ahead of them.

Extending access is relatively easy. However, doing it so that you meet more need will require designs that do not induce extra demand to clog up expanded services. That is far trickier.

Rebecca Rosen is senior fellow of health policy at the Nuffield Trust

1 Readers' comment