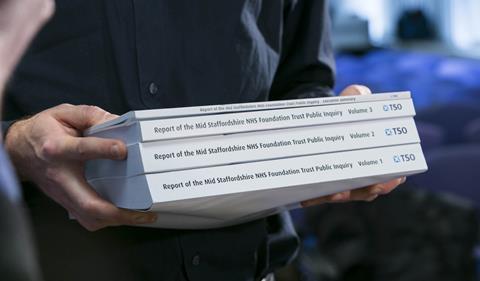

Ian McDowell talks to non-executive directors and governors and asks whether their roles need to be reimagined in the light of the failings at Mid Staffordshire

According to the NHS National Leadership Council’s The Healthy NHS Board, non-executive directors are there to “ensure the board acts in the best interests of the public” and “provide a safe point of access to the board for whistleblowers”.

In foundation trusts, non-executives are appointed by governors, a role transplanted from education. As in education, NHS governors can be either appointed or elected. They can be drawn from the communities who use the service, or from the staff body.

These are high-sounding roles, but the events at Mid Staffordhsire Foundation Trust have highlighted a more complex reality. Both Robert Francis QC, and the Mid Staffordshire non-executives themselves, pointed out that you may be established and respected locally, but you need facts to challenge convincingly.

‘I wouldn’t be able to sleep easily unless I had eaten the food the patients eat, walked the elderly wards’

And not just facts as traditionally understood: the formal ones that pepper the paperwork ascending through the system. Sir Stephen O’Brien, chair of Barts Health Trust, says he gets “very little assurance from the paperwork that flows upwards”. He sees the non-executive role as “lay by definition, not part of the clinical or management community, but part of the world of the patient”.

“I wouldn’t be able to sleep easily unless I had eaten the food the patients eat, walked the elderly wards. You have to be out there. I can’t think of any other way of doing it,” he says.

But how does this experiential knowledge flow upwards? And can it ever have parity with the empirical?

Challenging the data

A former BBC employee, who worked as an NHS non-executive director and was an independent convener for complaints, says: “A lot of talk about quality in the NHS is actually about quantity. The orchestrated reporting of data can begin to ring hollow for NHS boards. There needs to be a way of rooting these discussions.

“Storytelling is a powerful way of doing this,” he adds. Complaints are stories, and community narratives can do that very effectively, but it needs to be done systematically and not just on a whim or in pockets.”

‘Non-executive directors can easily be painted as servants of the dark arts, and governors as local cranks’

So stories, including complaints, can, and should, be used in board business; but they need to be woven into the fabric, rather than just sitting, however compellingly, on the surface.

“It’s the opposite of touchy-feely; it’s the ‘how do we know?’ question that every board member should have in their mind and on their lips. The data should challenge the stories; the stories should also challenge the data,” he explains.

In the case of another non-executive who influenced the improvement of a vital local wheelchair service, the trick was just this: finding the data behind the stories and the stories behind the data. “Data can be true; stories are more than true. They bring a problem to life.”

So non-executives and governors need an organisation culture where the heart can be engaged along with the head. “You have to mind when things are wrong; it has to make you angry”, says the ex-BBC non-executive, recalling an “inspired” away day for bth non-executive and executive directors where they were walked through the human implications of their decisions.

Dark arts

Where this quality of investment in relationships has been absent, a kind of splitting can occur, with business skills and local commitment at loggerheads.

Different groups of non-executives can also risk caricaturing each other. A former governor told me: “Non-executive directors can easily be painted as servants of the dark arts, and governors as local cranks.”

‘A director said: “We know what’s happening. We could be up for corporate manslaughter”’

But where these roles are properly integrated, trusts can move into a whole new dimension. Manchester Mental Health and Social Care Trust is currently preparing for foundation trust status. Its non-executives go on “leadership walks” organised in conjunction with the trust’s head of patient experience Patrick Cahoon. Their very human experiences while on these walks − tactile, sensory, emotional − are tested against quantitative data, including data from patient advice and liaison services and complaints.

Thomas Harrington, a member of the council of governors at Manchester, is rightly excited about his new role. “My aim is threefold. I want to educate the trust, the public and service users. I want to make it less scary for service users. Mental illness should be treated like any other type of illness.”

Veronica Beechey, lead governor at University College London Hospitals Foundation Trust for six years, took a similarly systematic approach there, setting up and chairing a high-quality patient care group for the governors. “The majority of governors have a democratic mandate, but they also need to know what’s happening on the ground. They need confidence, knowledge and respect within the organisation to effect change.”

Accepted picture

These are the signals to follow: non-executives and governors armed with the tools they need, where necessary, to “break the spell of the organisation” as another eminent former governor, now a commissioner of clinical education, puts it most tellingly.

A former non-executive who was involved in a crisis spanning four PCTs triggered by poor stroke and maternity data tells a story about this actually happening. The boardroom rigmarole suddenly rang hollow. “A director said: ‘We know what’s happening. We could be up for corporate manslaughter’. Everything went quiet.”

Christine Hancock, a leading commentator on global health, who has been a health authority chief executive as well as general secretary of the Royal College of Nursing, says: “Whatever systems you put in place those systems need a conscience. That might sound a bit flaky to some ears; but you have to ask ‘what makes really busy people stop in their tracks and act swiftly on something that doesn’t fit the accepted picture?’”

Governance needs to be understood experientially as well as structurally. Where both sides are in balance, the engine of accountability will really sing. It’s the difference between patients and communities shouting from the side-lines, and all of us pulling together: from patient power to patient-powered.

Ian McDowell is director at Both Sides NOW and a fellow of the Centre for Science and Policy at Cambridge University.

6 Readers' comments