With covid-19 cases surging first in London and resource pouring in to meet demand, other regions are in danger of missing out, leaving them less prepared to resist major damage from the pandemic. On top of this, hospitals in more remote areas, normally with older populations more susceptible to serious illness from covid-19, are already struggling, so may be vulnerable to meltdown when the virus arrives in earnest.

These concerns have been expressed by several hospital chiefs and other health leaders to HSJ in recent days.

While in many respects the NHS is coming together as a united front, the coronavirus outbreak is at the moment a highly regionalised feature in the UK. This is leading to tensions, and means highly contentious logistical decisions are having to be made. The outbreak’s final toll could depend on getting them right.

Regional tensions manifested first in the problems with testing. General hospitals in some areas feel it is taking them a long time to get results compared to those in or closer to big cities normally hosting the main testing centres. This is exaggerating the relative importance of the problem in some places, and delaying attention and awareness in others, as well as causing distress and delay to self-isolating staff wanting to return to work, they argue.

Expansion of testing may help with this, hopefully soon. But with surges either beginning or anticipated beyond London, frustrations are moving to intensive care staffing, ventilators and other breathing equipment, anxieties about oxygen supply, and to deployment of additional staff and new “field” facilities.

The most significant group of deaths outside London so far has been in the Black Country and Birmingham — not a rural area but one with several smaller hospitals, and a long way from the capital. NHS leaders in the patch have shared their fears about going unnoticed, underreported, and about what resource will arrive and when. Nearly one in five confirmed coronavirus cases so far are in the Midlands yet the capital still hogs the spotlight.

Trusts outside London have no information on what they will get in terms of equipment and, told they are unable to source their own directly, are already frustrated. One chief executive of hospitals serving a rural and coastal area said: “The perception is ventilators are going to where the decisions are made, which is London.” That CEO’s call is for the machines to be dished out based on population, not rushed to the areas where there is most “immediate” need — currently in London — as is the current official policy.

But the problem does not end with the scramble over equipment (the “stuff”). With London, Birmingham and Manchester setting up large field hospitals, there is also the appearance that the big urban centres are being prioritised for the two other “Ss” needed for meeting acute covid demand: staff and space.

A public health director serving a relatively rural patch in the north of England queried whether more dispersed field hospitals or similar supra-hospital capacity needed to be created in areas far away from the big centres: “Why are London, Manchester and Birmingham creating field hospital capacity when a lot of local healthcare systems do not appear to have made that call yet?

“It is likely that big cities will have higher numbers [of cases] but they also generally have a bigger number of beds already as teaching hospitals are concentrated in larger cities.”

Never so quiet

Alongside the panic is an otherworldly reality in plenty of hospitals of a temporary quiet, the “calm before the storm”. While crisis dominates on TV and food parcels flood in, plenty of hospitals outside of the surge areas are quieter than they have been in years. Discharge measures are working — helped by the fact that families, learning of the covid outbreak, have turned up to repatriate their relatives — and accident and emergency attendances for non-covid illness have plummeted.

The contrast between this quiet and parts of London now being overwhelmed, highlights why serious consideration is being given by the people in charge of coronavirus response operations of ferrying critical care resources, staff or kit, around the country towards the peaks, rather than seeking to share it out equally from day one.

There is even discussion of moving patients from area to area, and the creation of huge regionalised field hospitals indicates there could well be a lot of this.

Planners are modelling that, if there is enough time between peaks from region to region — or if some areas can substantially flatten the growith curve by getting measures in place before the virus spreads widely — then ferrying kit, staff or patients around at the right time could be the difference between coping and not. “Live decisions are being made. All options are on the table,” is the mantra from senior officials asked about these logistical choices.

Yet such suggestions are met with fury outside the early surge areas, especially while some feel their current covid-load is being underestimated.

A suggestion on an HSJ comments thread that “staff from outside London” should be asked “to come and run [the ExCel Centre Nightingale hospital] and then take the learning out to the regions when it spreads out” was met with disgust from some, railing against “pouring all the country’s resources into the never sated black-hole which is London’s need”.

Consideration has also been given to centralising intensive capacity at “hot” regional covid-19 sites (the larger acute centres which begin with more ITU resource and resilience), with other more vulnerable sites sending their cases in.

This idea faces big practical and logistical objections. Many smaller hospitals would be some distance away — making it difficult to transport large numbers of patients, even if they could be accurately triaged from non-covid cases and diverted at the right time.

Another trust chief executive running hospitals in large shire towns added: “We can expand local units by asking staff to work more shifts, getting retired staff to return and retraining theatre staff.

“If you told those extra staff that they were being shipped to the ICU in a bigger, more distant unit, many would decline.” On that particular patch, consideration of a huge centralisation of critical care has subsided for now.

Vulnerable hospitals

There is a set of hospitals which may be particularly vulnerable if, or when, there are large peaks of infection in their area.

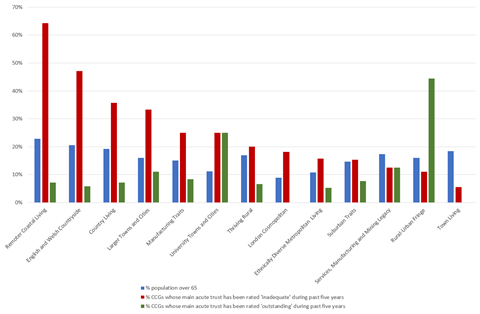

New HSJ analysis shows how area clusters away from the big conurbations — remote, coastal and rural areas, and the large towns/small cities — have bigger older populations who are at risk of covid-19 serious illness; and are more often served by acute trusts which have been rated “inadequate” at some point during the past five years, so likely to be more vulnerable. Others have highlighted how these areas tend to have fewer critical care beds. Neither fact means they are necessarily struggling now, or will certainly fair worse when the virus hits, but they illustrate why some are concerned.

This maps shows the acute trusts which have been rated “inadequate” at some point in the past five years, and the size of the circle shows the share of their population aged 65 and over (hover mouse to see the figures).

Louella Vaughan of the Nuffield Trust has suggested a different national support package is needed for smaller and more isolated hospitals, like sending staff and military capacity to them, rather than centralising it in urban centres.

At the extreme example, very small, very isolated hospitals in the Highlands have extremely low capability to cope with staff going off sick and with supplies potentially some way off. Gordon Caldwell, at Lorn and Islands Hospital, in Oban, in the Highlands, is giving his account of some of the challenges on Twitter.

With the proviso that the data is very noisy, the current pattern of covid-19 in England show confirmed cases are overwhelmingly concentrated in London, with other notable concentrations in Wolverhampton and in rural Cumbria; but that mortality on a per head basis is more distributed — with large numbers at Portsmouth and Frimley Park (Surrey and Berkshire) and the Black Country. It is far too early to know why or what that means.

Those running hospital services away from the big urban centres are hoping they will benefit from having a bit more time than London to prepare. “We will be as prepared as we can,” is the best assurance they can honestly give, while crossing fingers recent tough distancing measures, along with their more dispersed populations, will mean they can stave off large, steep spikes in infection.

One chief exec of hospitals away from big urban centres said: “London took the brunt of no social distancing with the added problem of dense population and use of public transport. Hopefully rural areas will fare better (hopefully).”

If they do not, it could be those areas where the impact is felt even harder.

5 Readers' comments