The short termist ‘hotpotch’ of measures taken by the government does nothing to stem the growing pressures on social care

Comedy genius Peter Cook once observed, “I have learned from my mistakes and I am sure I can repeat them exactly.” In treating social care very differently from the NHS, the government has repeated the mistakes of the 2010 and 2013 spending reviews.

‘Poorer areas with a low council tax base will be able to raise much less than richer areas’

This time, the water has been muddied by the introduction of a new funding element – the ability of local authorities to levy a ‘precept’ on council tax by up to 2 per cent, on condition that it is spent on social care – and the unexpected addition of £1.5bn to the Better Care Fund. The latter appears to be genuinely new money for social care and not raided from the separate, previously announced increases for the NHS.

Together with the planned shift from general government grant to locally raised revenue – and more cuts to the former – this is a tricky settlement to gauge. The Treasury says that the council tax precept could raise as much as £2bn by 2019, a claim that appears to rest on heroic assumptions about the willingness of councils to hike council tax by the full 2 per cent, not just for one year but the next four – on top of any other rise for other services.

We will only begin to understand the overall impact when all 152 local authorities have set their budgets for next year.

Double-whammy of cuts

The problems with a local precept for social care are obvious. Our analysis shows that poorer areas with a low council tax base will be able to raise much less than richer areas – ranging from £5 per head of adult population to £13. And they face a double whammy because of cuts to central government grant, which forms a bigger source of their revenue.

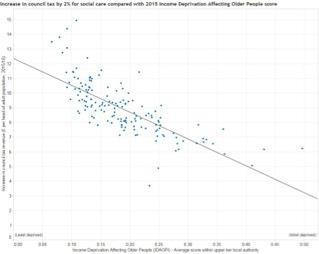

These areas also happen to be places with relatively high levels of need for publicly funded social care. This is illustrated starkly in graph 1, which shows how places with high levels of income deprivation among older people – a good proxy measure for social care need – will raise much less than wealthier areas.

This is the new inverse care law. Setting aside the distributional inequity, even if every council chose to levy the maximum precept, the £390m raised would fall well short of the £700m – and rising – funding gap.

Graph 1: The social care precept and deprivation

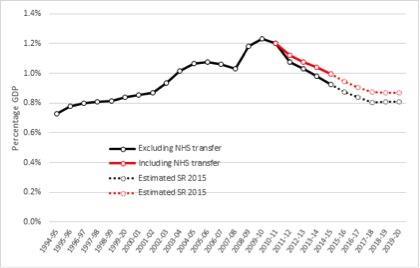

Another downside of the settlement is that the known additional money is back-loaded – the new Better Care Fund money does not come through until 2017, and then provides only an extra £100m in the first year (graph 2). “Too little too late” is how the Association of Directors of Adult Social Services has described it.

It is not clear how much of this councils will be able to use to bolster their baseline budgets. Against a background of dwindling financial support from central government, real terms spending on social care is set to fall again for the next three years.

There is little succour here for local authority commissioners and providers. Given the increasing fragility of the provider market, this is very high risk.

Graph 2: Changes in real terms spending on adult social care 2009-2020

The requirement for all areas to produce local integration plans to be implemented by 2020 is very significant. This echoes the recommendations of our report earlier this year on integrated commissioning and it is heartening that the government has eschewed top-down prescription in favour of locally generated arrangements. This is one instance where the government does appear to have learnt from past mistakes.

‘This is not a recipe for equitable and effective funding’

Although it is unclear how this relates to the NHS Five Year Forward View vanguard programme, it could herald the development of truly place-based approaches to health and social care.

It is ironic, then, that while this aspect of the spending review sharpens the convergence between health and social care delivery, the shift away from central funding towards locally based revenue – council tax and business rates – will cause the funding of these two sets of services to diverge even further.

Whereas the NHS will continue to be funded mostly through general taxation, social care will be more reliant on local levels of property wealth and economic activity. This is not a recipe for equitable and effective funding unless accompanied by a robust equalisation arrangement at national level (there will be a formal consultation about this very radical shift).

Disincentive to share

A further problem is that despite the policy rhetoric about integration, the extent of cuts outside the NHS ringfence – even to health-related services, notably public health – creates a powerful disincentive to share resources. Policy is heading in one direction, the money in another.

‘The outcome for social care is not as awful as it could have been, but it is nowhere near as good as it needs to be’

But perhaps the most disappointing aspect of the spending review is its short term focus. By ignoring the consequences of an ageing population and the rise in long term conditions, this will test – almost to destruction – the faultline between universal NHS care provided free at the point of use, and heavily rationed and means-tested social care.

Instead of a fundamental root and branch review of how entitlements, as well as funding, are aligned across the NHS and social care, as proposed by the Barker commission, the government has chosen an opaque and messy hotchpotch of measures, which fails to address the short term pressures on social care; it does nothing to place funding on a more sustainable footing in the longer term.

Looking at the settlement in the round, the outcome for social care is not as awful as it could have been, but it is nowhere near as good as it needs to be. Taking account of NHS transfers, the new money for the Better Care Fund, and making relatively optimistic assumptions about how much will be raised through the social care precept, spending on adult social care will fall from 1.2 per cent in 2009 to just 0.9 per cent by the end of the parliament – back to the same level as 2001 (graph 3).

Graph 3: Adult social care spending as a percentage of GDP in England, 1994/5 to 2019/20

We are going backwards. Based on this assessment, the social care system in its current form will not survive. The consequences for people with care and support needs, their carers and families, and the NHS are stark.

Richard Humphries is assistant director for policy at the King’s Fund

1 Readers' comment