The surgical workforce has a key role to play in the current crisis which requires adaptation and cooperation, write Emily A.H. Duggan, Alex C.G. Armstrong, Justin C.R. Wormald and Mark M. Mikhail

Summary: In December 2019 evidence of an emerging highly contagious and virulent pathogen began to surface. Since that time the world has been engulfed in a pandemic which has infected over 1.8 million people. This has drastic changes to our lifestyles and working practices. Surgeons must adapt and contribute to the current crisis as leaders. This article seeks to provide a review of current evidence and impact as well as crisis management plans that are being put in place nationally and internationally. The surgical workload is changing with elimination of elective work but there must be caution to not compromise emergency and cancer care. The Royal College of Surgeons and General Medical Council have given guidance on how surgeons can adapt and the key role workforce planning is playing. There are significant contributions that surgeons can make but they must ensure they are in the strongest position to make them.

The supportive treatment and ventilatory assistance that coronavirus patients require is not in the surgeon’s repertoire. Internationally the trend has been for hospital specialties to become more sub-specialised over the years with many studies showing patient outcomes are significantly improved when surgical patients are managed in a shared care model. Demonstrated in Trauma and Orthopaedics where there has been a dramatic growth in the subspecialty of orthogeriatrics. Guidelines on the management of medical conditions memorised during formative years are unlikely to have remained best practice. As such, surgical colleagues are realising and must openly publicise their shortcomings as well as their skills.

The Royal College of Surgeons has stated that the “overarching principles” for the NHS and the nation to get through the current pandemic are:

i) To triage and deliver healthcare to patients for maximal benefit, as in a mass casualty scenario.

ii) To protect and preserve the surgical workforce.

Managing key services (emergencies and cancer)

Emergency and trauma surgery as well as oncology must continue during any time of crisis. Although not unexpected, it is well documented that key services decline in times of national crisis eg war. During the West African ebola crisis many more people died of malaria than ebola as a result of the diversion of resources. Manpower reduction (surgical and administrative), missed appointments, cancelled operating lists and bed shortages are causing barriers to maintaining a good service. A more flexible approach is needed that allows patients to look after dependants, ensure a safe place to recover and be able to travel to and from the hospital safely.

In order to reduce hospital footfall outpatient appointments are restricted to those that are deemed essential, all others are cancelled or held remotely.

Operative Management

Surgical decisions are being altered, where required, to reduce the burden on critical care, outpatients and primary care. Non-essential operations are being postponed, or non-surgical management options considered. Examples include fashioning a stoma rather than primary anastomosis to reduce risk of requiring a post-operative critical care bed; increasing trials of conservative management of fractures or ligamentous injuries; utilising absorbable sutures for wound closure. Patients are being empowered to change their own dressings and contact the particular service only in the event of an issue arising. These are, at times, uncomfortable decisions for health professions, but needed from surgical leaders at this time.

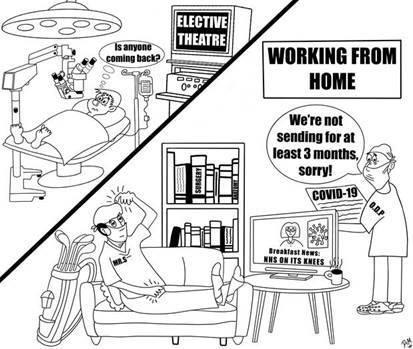

Elective Work

In the UK the halt of elective work has been mandated within the NHS. Private hospitals have been asked to “donate” their hospital bed capacity to the NHS crisis – with the assurance that the bed, resource and staff usage will be paid at cost price. This is a better commercial position for private hospitals to be in rather than empty wards but will pose problems when starting back up again.

Managing the Team

The Royal College of Surgeons has advised on the priorities that surgical departments should adhere to. There are circumstances where these priorities are achieved with a surplus of time, staff or both. In these circumstances the advice is that individuals should fulfil alternate surgical roles or, if these are already covered, alternate non-surgical roles.

This change in working practices, which may require individuals to work outside of their regular comfort zone, scope of practice and even specialty is troubling to many surgeons should their actions and decisions be called into question in the future. The General Medical Council has released a statement recognising these concerns and confirming that in cases where issues are raised in these challenging circumstances, each case will be considered on an individual basis.

In order for any team to contribute in a meaningful way during a time of crisis, it needs to be in good health, well prepared and present in maximum numbers. One in four NHS doctors are currently off work. In this regard, a major priority and responsibility rests on individuals to try, where they can, to remain well. This means dividing departments and partially deploying employees to keep a healthy staff “reserve”.

Supporting colleagues

The skillset that makes a good surgeon is broader than a good technician. Contributing may be as simple as deploying to the Emergency Department to triage and manage minor injuries. Medical teams are facing an influx of patients and are overwhelmed in a swathe of information and increased duties. Practical help may involve manning phones, contacting patient relatives and even breaking bad news.

Senior surgeons are often respected by their juniors and this is a weight of responsibility in the midst of “fake news” and disinformation. There are many unknowns and all of the modelling we are basing decisions and opinions on is estimation. Many colleagues are joining the workforce, having just finished medical school. As leaders it is a responsibility to project calm and be choice with words and support.

Managing the Fallout

As we emerge from the crisis, a mammoth and complex task of “catch-up” will be ahead. The projected number of cancelled elective procedures is unclear. In the third quarter of 2019 over 2 million elective operations were scheduled and we were already behind target. How and when these operations are allocated will need careful planning and new targets. Many patients’ presenting conditions and co-morbidities will have worsened potentially to inoperable disease; investigations may need repeating. Missed cases will need to be identified and managed. It is during this time, after the panic and dystopian reality has subsided, that the current public support for healthcare professionals internationally may waiver. This influx of elective work may see a boom in the private sector as the NHS struggles to fulfil new targets.

With health systems around the globe in crisis there is innovation occurring in days that has previously taken years. Changes in practice that outlast the pandemic, such as a reduction in follow-up outpatient appointments, will reduce the pressure the health service experiences in normal circumstances. Telemedicine will strengthen its foothold, resulting in improving patient convenience and specialist accessibility. With much of the outpatient delivery of healthcare put on hold or managed remotely there may well be a paradigm shift in patient expectations. More patients may be willing to be educated on their disease and their post-operative course. More importantly, if there is a sustained cohesion and cooperation between specialties, departments and people this could profoundly improve work morale and patient outcomes moving forward. Surgeons should be at the forefront of these changes.

Key Messages

- The surgical workforce has a key role to play in the current crisis which requires adaptation and cooperation.

- Emergencies, trauma and oncological surgery must continue with as little disruption as possible, but with vital and considered changes in delivery.

- Healthcare will not be the same again after the pandemic passes; there will be positives that can be applied for the betterment of the NHS

1 Readers' comment