Commissioners and clinicians can improve the value yielded by their respiratory programme budget by rebalancing investment in non-medical and medical interventions, writes Siân Williams

In 2010/11, the NHS in England spent more than £4bn on respiratory illness, £720 million of it on chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). A clinical commissioning group could expect to spend in the range of £12m to £40m a year on respiratory disease depending on its size and demography.

The just-published Respiratory Atlas of Variation illustrates the variation in outcome for that expenditure. So what are the best interventions to invest in if we want to reduce mortality from COPD and reduce the burden of breathlessness and other associated problems?

In COPD there is scope to increase investment in stop smoking services and pulmonary rehabilitation programmes, and reduce overuse of some inhaled medicines.

‘How could we extract most value from the major investments commissioners make, using programme budgets as the benchmark, rather than making changes at the margins?’

These are the findings from the clinical network IMPRESS, a joint initiative between the British Thoracic Society (BTS) and the Primary Care Respiratory Society UK (PCRS UK) in collaboration with the London School of Economics and Political Science (LSE) School of Management, supported by the Health Foundation. Even if you are not interested in COPD or respiratory disease it is worth reading on because the methodology we used is a helpful way of engaging local stakeholders in difficult but important resource allocation decisions.

IMPRESS built on its previous findings about where there was underuse, overuse, misuse and under-coordination in respiratory services.

Our starting point was the definition of value as outcomes divided by cost. How could we extract most value from the major investments commissioners make, using programme budgets as the benchmark, rather than making changes at the margins?

COPD misuse and undersuse

Underuse

- Smoking cessation Inhaled corticosteroids for patients with asthma prescribed LABAs (long acting beta agonists)

- Reviews of patients with asthma requesting excess SABAs (short acting beta agonists) with no other treatments

- Underuse of audit of adverse effects eg percentage of children prescribed or using >800 micrograms per day of inhaled beclometasone who are not under the care of a specialist respiratory physician

- Overuse of enteric-coated prednisolone tablets for patients with COPD or asthma instead of uncoated prednisolone tablets. At the time of drafting (Jan 2010) there was a six-fold difference on the drug tariff

- Person-centred consultation and records review to identify and support people with poor asthma control

- Referral to pulmonary rehabilitation

- Psychological support

Misuse/overuse

- Oxygen prescribing

- Inhaler waste

- High dose inhaled corticosteroids and/or combination products

- Hospital beds (eg asthma admissions and COPD length of stay) and underuse of hospital respiratory specialist care

- Outpatients for common conditions

Under-coordination

- With social care

Decision conferencing

Decision conferencing is a great way to use the evidence, local expertise and experience to try to answer that question. It starts from the real-life premise that resource allocation is not a technocratic process but a social one. It involves judgement, debate, argument and unequal knowledge. Therefore decision conferencing embraces this.

By involving stakeholders and using visual models that are easy to grasp it increases ownership of the decision, and will assist with implementation. It has been used by the team at LSE to support public policy decisions, and by NHS Sheffield and the Isle of Wight.

The process looks at the scale of impact that interventions have on costs and on a population’s health. In the case of IMPRESS, we brought together a team of primary and secondary care nurses, doctors and managers with a special interest in respiratory disease.

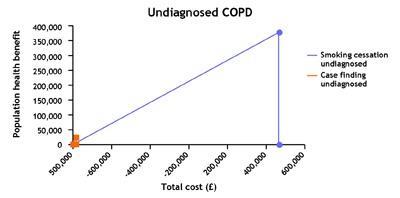

We used the evidence and our experience to describe an archetypal population, because we do not work in the same locality. We modelled a population of 300,000 including about 12,000 at risk of COPD of varying degrees of severity. If this was done by a CCG, then you would use the data about your local population.

‘The process looks at the scale of impact that interventions have on costs and on a population’s health’

We held two workshops. In all the discussions we based as far as possible our judgement on the published evidence assessing its robustness and applicability to our population. At the first, facilitated by the LSE, we were asked firstly to generate a list of interventions for COPD.

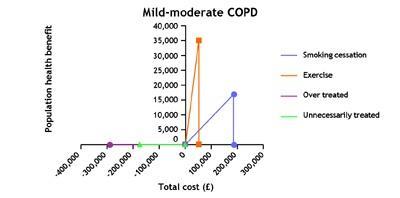

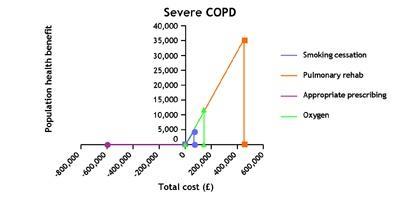

We produced a long list of these and categorised them by patient segment. After much discussion we ended up with three: undiagnosed, diagnosed with mild-moderate disease and diagnosed with severe disease. Our dream had been to segment by pack years of cigarettes smoked, or by degrees of breathlessness. However, we had to put this on one side as the published evidence is not categorised that way. We then organised literature searches to find any relevant health economics studies and were taught, using a simple format, how to critique these.

At a second facilitated workshop, we were asked in plenary session, one by one, to rank the benefits of the interventions for an archetypal individual using a visual analogue scale of 0-100. We went round the room until we could agree on a consensus. We then, based on our groundwork, agreed on how many people would benefit in a local population. For example, we decided that for a population with diagnosed severe COPD, stop smoking would have an index of 100.

We argued that 670 people would benefit sand about 50 would have quit at one year (not the four weeks measured now). In the population with diagnosed mild-moderate COPD, we gave stop smoking a score of 130 – compared with the 100 in the severe group. We estimated about 130 with mild-moderate disease would stop at one year. From these, the LSE team produced rectangles: the size of the rectangle indicates the size of the population health gain/benefit.

Cost of interventions

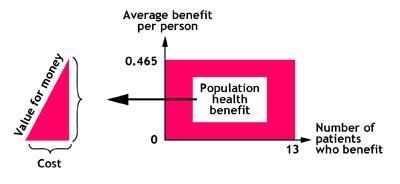

However, this does not tell you about cost. Therefore the next stage was to agree the cost of the interventions. These figures were then fed into a statistical programme in real time to produce value for money triangles.

The comparative size of the triangles guides you as to the relative value of the interventions. A small base indicates a low cost; a large base, a high cost. A steep slope indicates good value, and a shallow slope poor value. This gives you a visual representation of where there is scope to reduce expenditure on lower-value interventions and increase expenditure on higher value.

In our case, the key finding was that interventions to help those people with COPD who smoke to stop, about 35 per cent, improve their outcomes at a relatively low cost and therefore, given the number of people who smoke, offer value not just to the individuals but also to the population. This is true both for those diagnosed with COPD who smoke and those with COPD who smoke but are as yet undiagnosed, estimated to be as many as 6000 in a population of 300,000. Yet in our experience stop smoking services are not routinely offered in hospitals (acute and psychiatric) or in other places where there are likely to be substantial numbers of people who smoke.

We also argued that there is substantial overtreatment with inhaled medicines for patients with mild to moderate disease and that in some cases this might create health problems. In particular, we warn of the risks of prescribing “triple therapy” - multiple inhaled treatments in this group – both because of the risk of causing harm and because of unnecessarily high costs.

Programmes of pulmonary rehabilitation – combining exercise, education and self-management for groups – are particularly cost-effective ways of improving patient outcomes but are under-supplied in many parts of the country.

The cost-effectiveness data suggests the current sequence of management may need reordering so that interventions such as stop smoking and consideration for referral to pulmonary rehabilitation should happen before any trial of triple therapy.

What might make clinicians be prepared to change?

Bringing everyone together to discuss the evidence using this cost and outcomes framework is very powerful. Few of us are confident in health economics – this gives people a chance to learn and to improve their understanding and to see where the gaps are and make collaborative judgements to fill the gaps.

Healthcare professionals have an ethical responsibility to avoid waste, which means doing what’s best for a patient’s health and avoiding treatments which do not improve things or which actually make them worse.

We have tended to see stop smoking interventions as something carried out by public health programmes rather than as every clinician’s business. We should be arguing for greater investment in specialist stop smoking services for patients and also for education programmes for all clinicians to have the skills to help people quit.

What could you do

- Decide on a topic: eg COPD spend and outcome

- Invite stakeholders

- Appoint a public health facilitator

- Bring cost-effectiveness evidence of different interventions

- Collate public health data about your local at risk population

- Run a decision conference

- View the value triangles and discuss the implications

- Make a business case for change. For example:

- Increase expenditure on stop smoking services directed at people at risk of COPD and those with COPD and other long term conditions who smoke. This might mean reallocation of existing stop smoking services or increased investment. It may mean compiling and reviewing spend on stop smoking medicines as well as on stop smoking counselling: the business case is for both together.

- Set up a primary-secondary care responsible respiratory prescribing committee involving medicines management and prescribers to review inhaled medicine use; compare to the guidelines for asthma and COPD. In particular review triple therapy use against the guideline: triple therapy should be reserved for patients for whom it is appropriate: for people with severe disease who have persistent exacerbations despite using either ICS/LABA or LAMA. - Provide regular feedback to prescribers and ensure they are all aware of the costs. For example in NHS London, prescribers did not previously realise that respiratory inhalers are the number one medicines cost to the NHS.

- Use incentives such as CQINS or LES to encourage stop smoking as a treatment and referral to pulmonary rehabilitation. IMPRESS offers examples.

Siân Williams is IMPRESS programme manager

9 Readers' comments