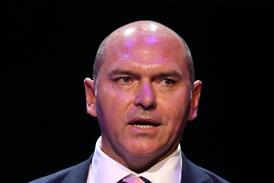

When Sir Simon Stevens was appointed chief executive of NHS England in the autumn of 2013, HSJ commented – tongue-in-cheek – that he now had the chance to save the NHS for the second time.

Taking our tongue out of cheek, let us now state that he has actually managed to do it on three occasions.

Nobody will ever take Aneurin Bevan’s place as the NHS’s most iconic figure, but there is now a clear runner up.

The first time plain Mr Stevens, as he then was then, ‘saved the NHS’ came in the early 2000s, beginning as highly proactive special adviser to health secretary Alan Milburn, and then to prime minister Tony Blair. During that time – when he effectively ran the NHS from a desk in No10 – the service saw more money and effective reform than at any time in its history.

When the cash crunch came in 2010, the NHS survived because of resilience provided by that money and those reforms.

Sir Simon’s task when he became NHS England chief executive in April 2014 was to rescue the service from the disaster of Lansley reforms, amid ongoing fallout from the financial crash.

This he accomplished with a bravado unsurpassed by any British public servant. He was admittedly aided by the tacit agreement of the coalition to undoing the 2012 Act, but the speed with which he put in place a series of workarounds to effectively neuter the more damaging aspects of the legislation was often breath-taking. The entire service was soon working to a system designed by Sir Simon and which paid little attention to laws passed just a couple of years beforehand.

Part of this rescue package was to win more money for the NHS. This Sir Simon achieved with a brinkmanship which would few in his position would have even contemplated. Time and again, speaking truth to power and publicly setting out what would happen if the service’s requests were denied.

And then came the pandemic. The NHS’s success during its greatest challenge was by no means assured. Politicians, public and the media could have easily turned on the service at a number of points if it had screwed up – letting intensive care become overwhelmed in the first wave for example, or having to cancel urgent cancer operations on a national basis.

The vaccination programme, of course, is the crowning glory and HSJ knows that Sir Simon was planning this long before the first vaccine was even authorised.

The covid inquiry – when it arrives – will show a more nuanced picture. But in the heat of the battle Sir Simon kept the service going and, as a result, it rose even higher in the public’s estimation at a time when failure may have – once again — created existential consequences.

But Sir Simon’s time as the NHS England boss has not been without its missteps.

In one sense, his seven year term has not allowed him to do what he was hired for. The greatest strategic health policy thinker of his generation was forced to move from one set of tactical challenges to another.

Indeed, it is harder to think of a more difficult environment in which to drive forward strategic change than one presented by austerity, Brexit and the pandemic. Because of this, we may have not have seen the best of Simon Stevens – though it is also essential to add that no other healthcare leader was better equipped to meet those challenges.

Sir Simon was not always right in his policy priorities. He took too long to realise the seriousness of the NHS’s workforce challenge and has only recently started to ‘get’ the importance of technology in transforming health services.

He, of course, also leaves the NHS with longer elective waiting lists than when he started to tackle them at the turn of the century – although he can hardly be blamed for the circumstances that created this situation.

His running of NHS England varied between the admirably light-touch to the careless. For every five colleagues inspired by working for him, there is one bruised by the wielding of his intellect and desire to control the messages the organisation sent out to various stakeholders.

Sir Simon’s personal style was also one that inspired admiration – sometimes even awe — as well as irritation, and sometimes even rage.

Many of the politicians who worked closely with him openly admit his political skills and nous far surpassed theirs. As did, HSJ will note, his desire, even glee, in engaging it with the most powerful people in the land.

He managed to act like a politician – while also appearing at the same time to be above such sordid business. No wonder he often drove No10 and No11 advisers mad.

Sir Simon changed his mind on a regular basis, but was always able to explain in the most eloquent terms why an apparent change of direction was a logical extension of previous policy.

He could be ruthless – even to friends – but set a spotless example of how to behave as a public servant.

What really counts is the NHS that Sir Simon leaves. It is one which takes mental health, primary care and racial equality more seriously than at any time in its history, which has survived the pandemic much better than many of its international counterparts, is saying goodbye to the wasteful internal market and which the English public believe is the finest thing about the country they live in.

When he joined as NHS England CEO in 2014 its annual spend was £97bn. As he leaves, it is over £150bn. That figure, of course, is swelled by covid funding, but the underlying trend since 2014 is impressive given the times and the £150bn figure is the one to which political opponents and future NHS leaders will hold the government. If nothing else, that is not a bad seven years work.

Source

ual

Exclusive: Stevens to step down in July

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

Currently reading

Currently readingStevens has been the most important figure in NHS history since Bevan

- 5

- 6

30 Readers' comments