An open book accounting approach to NHS finances could lead to a more honest debate about the costs of care and funding models, write Naomi Chambers and colleagues

Colleagues at Manchester Business School are working on a Department of Health/National Institute for Health Research funded research project examining the use of patient level information and costing systems (PLICS), which is due to report in summer 2015.

‘An open book accounting approach to NHS finances could enable a more honest public debate about the costs of care’

According to the King’s Fund’s most recent quarterly monitoring report, two-thirds of trust finance directors are “very” or “fairly” concerned about balancing the books by the end of 2015-16. We also know that the public are concerned, as patients, about access to timely, comprehensive services of high quality, but also, as taxpayers, about waste and inefficiency in the NHS.

There is a line of argument that an open book accounting approach to NHS finances – an open book NHS – could enable a more honest public debate about the costs of care and about current and future funding models.

Our research sets out to establish how individual patient costs, which is the actual cost of treating patients, not the tariff or local contracts, are being used by hospitals and who that information is shared with.

- CSU sector income is £50m above expectations

- Gloves off: trusts’ new obligations in procurement

- More finance news and resources

Four key areas

The research aims to find out how PLICS can help in four areas: cost improvement; better resource allocation and congruence with patient preference; understanding clinical variation and the relationships between cost and quality; and greater clinical engagement through more clinical ownership of costs and information systems.

‘Providers are going to commissioners armed with PLICS data to drive local tariff negotiations’

The recommendations will be relevant to acute hospital trusts and commissioners, as any cash savings through the successful use of PLICS can, potentially, be redeployed across services and settings.

A clear and in-depth understanding of patient level costing and related outcomes can provide opportunities to develop a value based public healthcare system. The creation of public value in healthcare focuses on treating patients in ways that maximise the best outcomes for them, at the same time as minimising costs.

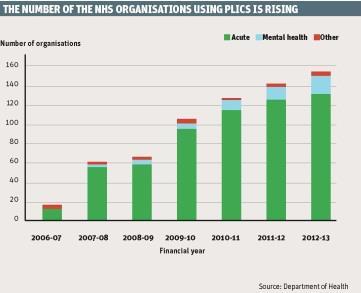

PLICS has been implemented in the NHS on a voluntary basis since 2007 (see graph, below). It is activity based costing, a method of recording all significant activities that happen to an individual patient from the time of admission until the time of discharge, and of calculating the resources consumed by using actual costs incurred by the organisation.

As part of the research, a survey was carried out last year to find out how the NHS uses PLICS, to which 98 acute and specialist provider organisations responded. The survey results showed:

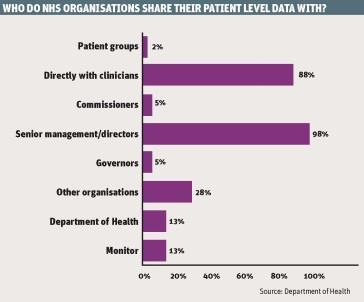

- PLICS data was shared nearly all the time with senior managers and clinicians, sometimes with other organisations, particularly through membership of a benchmarking club, but hardly ever with foundation trust governors, commissioners or patient groups (see graph, below);

- nearly three-quarters of respondents considered PLICS data to be commercially sensitive;

- PLICS is used widely to develop business cases, compare costs with tariff, compare different specialties and to inform and engage clinicians;

- it is used less often to examine the relationship between costs and clinical quality and clinical outcomes; and

- 40 per cent of respondents reported that data was collected or presented in a way that would allow costing based on a year of care.

In addition, our research includes deeper inquiry at four case study sites, including a series of interviews with key informants and extensive documentary analysis. So far the research has found:

- PLICS has not yet fulfilled its potential – although it is available, it is not used as a matter of routine in many hospitals;

- it can be resource intensive to administer and to use;

- some of the financial data used to construct PLICS, such as the allocation of overheads or indirect costs, lacks granularity and can be perceived as crude or inaccurate, thus eroding its credibility with clinicians; and

- further confirmation that the data is considered commercially sensitive, which is why it is generally not shared outside the institution, except in benchmarking clubs.

On the other hand:

- Monitor is keen to use PLICS as one of the tools to reform the tariff based payment system and set prices;

- there are examples of providers going to commissioners armed with PLICS data to drive local tariff negotiations;

- providers are finding PLICS useful to develop business cases and to guide investment decisions, and to take action about “loss making” specialties and services;

- PLICS is helpful in discussions with clinicians about the financial consequences of treatment pathways that go beyond or deviate from those agreed with commissioners; and

- there is optimism that, in an era of “protocolised care”, PLICS can provoke “interesting conversations” with clinicians about how their practice drives costs, their choice of consumables, the range and frequency of diagnostic tests requested and so on.

By having detailed costs broken down into actual resources used, clinicians and managers can review cost variations in similar patients or between consultants. Some trusts such as Birmingham Children’s Hospital Foundation Trust are also moving toward creating cost profiles of typical patients, based on the historic PLICS data that shows typical clinician choices for a particular group of patients.

Such cost profiles go beyond the current health resource group, which specifies only “with” or “without” complications, creating an average cost per patient that is in line with actual resources used. PLICS is also proving useful to drive up productivity and to compare costs across different hospitals in benchmarking clubs.

Unhelpful orthodoxy

But there are skills and structural barriers that hold the NHS back from fully using patient level costing data. Financial data has to be presented in ways that clinicians can understand and find useful and engaging.

‘There will be a significant limit to usefulness and impact if the process all takes place behind closed doors’

Monitor, in Closing the NHS Funding Gap report in October, estimated that more than a third of the savings required in the NHS can be found from reducing lengths of stay and by caring for people in the most cost effective settings. Many NHS trusts have a lack of formal mechanisms for joint working between clinicians and finance managers.

The Department of Health published the national best practice guide for effective clinical and financial engagement in November to pave the way for such partnership working in the NHS. It is difficult to see how productivity can be improved, best practice identified and costs brought down without this type of partnership approach using patient level costings, and for this to be linked to an analysis of the relationship between cost and quality.

The dominant business orthodoxy in the NHS, in which competitive advantage trumps public value, and which discourages the discussion of information about costs of care with other providers and with commissioners, is unhelpful.

There will be a significant limit to usefulness and impact if the process all takes place behind closed doors, inside and not between institutions, and is not shared with commissioners and the public.

Opacity is understandable when trusts are fighting to keep services by competing in tender exercises with outside parties that do not have to open their books. Putting aside commercial confidences must also require commercial approaches to be used sensitively to the wider needs of the NHS.

More information

- See the full set of PLICS data

Naomi Chambers is professor of healthcare management, Sue Llewellyn is professor of accountability and management control, Mahmood Adil is visiting professor of value based healthcare, Chris Wood is a research project manager and Christos Begkos is a research associate at Manchester Business School; Sheila Ellwood is professor of financial reporting at Bristol University. The views expressed in the article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the Health Services and Delivery Research Programme, the NIHR, the NHS or the Department of Health.

Downloads

PLICS DATA

Excel

3 Readers' comments