The draft NHS contract for 2015-16 needs 18 week sanctions to be balanced, commissioners’ discretion on perverse sanctions and no requirement to collect PTLs, writes Rob Findlay

The relative balance between the three 18 weeks sanctions means they perversely discourage providers from treating their long waiting elective patients. As a result, patients wait longer.

This should be remedied by:

- changing the balance between the sanctions so that the incomplete pathways sanction comes to the fore, and the perverse admitted and non-admitted sanctions are omitted or minimised; and

- if they are not omitted, giving commissioners discretion to waive in advance the admitted and non-admitted sanctions if the provider has foreseen the breach and has suitable plans to recover and sustain short waiting times safely thereafter.

Also the proposed requirement to submit cross-checkable weekly waiting list data would be a significant burden on trusts and should be dropped.

- More coverage of the NHS planning guidance

- Findlay: The NHS contract will make perverse targets worse for hospitals

- 18 week waits, October 2014: explore the maps

Why admitted and non-admitted sanctions are perverse

As the health secretary Jeremy Hunt said in his speech of 4 August:

“When the NHS started measuring performance against the 18 week target in 2007, something perverse happened. If faced with a choice

between treating a patient who had missed the 18 week target or someone who had not yet reached it, the incentive was to treat the person who had not yet missed the target rather than someone who had because that would help the performance statistics, whereas dealing with the long waiter would not. So a target intended to do the right thing ended up incentivising precisely the wrong thing.”

The benefit of waiving the admitted and non-admitted targets was also acknowledged by NHS England during the recent “amnesty”, when those perverse sanctions were lifted from July to November 2014 to allow trusts to treat their long waiters with less restriction.

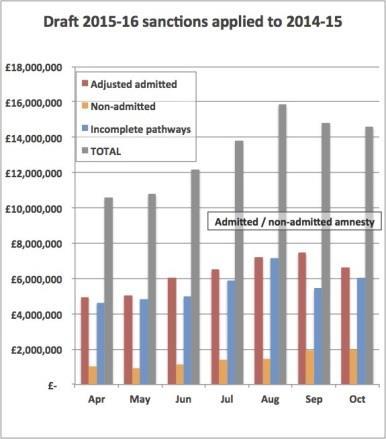

The current dominance of the perverse sanctions can be seen by applying the draft 2015-16 sanctions to the observed breaches seen in this financial year so far (Apr-Oct 2014 data).

‘There is historical evidence that strengthening incomplete pathways sanctions is effective’

Some 58 per cent of the total sanction value would be perversely extracted from trusts for treating long waiting patients, compared with only 42 per cent where trusts kept those patients waiting.

The perverse admitted and non-admitted sanctions dominate in every single month, even before the recent amnesty gave trusts greater freedom to treat their long waiting patients.

There is also historical evidence that strengthening the incomplete pathways sanctions, relative to the admitted and non-admitted sanctions, has already been effective at shortening waiting times and reducing the prevalence of perverse waiting list management.

Tip of the iceberg

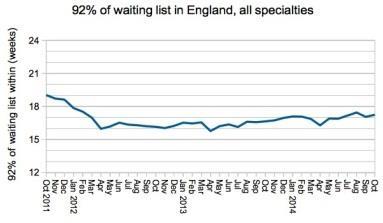

The introduction of the incomplete pathways sanction in April 2012 caused 92nd percentile incomplete pathway waits to fall sharply below 18 weeks for the first time ever, and they have since remained below 18 weeks even though the English waiting list has grown rapidly to a size not seen since early 2008.

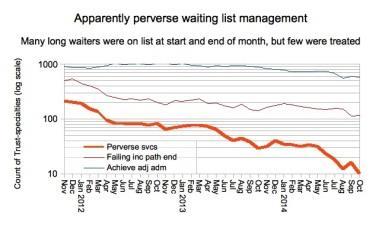

Perverse waiting list management also reduced as incomplete pathway sanctions were given greater prominence.

‘The most clearly defined cases are just the tip of the iceberg’

The most clearly defined cases are just the tip of the iceberg: these are specialties within trusts that perversely achieved the admitted and non-admitted target during a given month, even though they were breaching the incomplete pathways target at both the start and end of the month.

Over 200 services fell into this category in late 2012; the number fell to around 80 when the incomplete pathway sanctions were introduced in April 2012; then numbers declined steadily to 30 before the amnesty on perverse sanctions was announced in early summer 2014; and they fell sharply into the teens during the amnesty itself.

There is a further point against the admitted and non-admitted data, which is that it describes yesterday’s problem. Incomplete pathways, on the other hand, describe patients who are still waiting and on whom managers should focus their attention.

Counter arguments for retaining admitted and non-admitted sanctions

I am aware of a number of counter arguments that are sometimes raised in favour of the admitted and non-admitted targets, and will discuss them now.

Counter argument 1: “Waiting list snapshots are only taken once a month, so providers might let their lists blow out during the month and then give them a quick shove to achieve the incomplete pathways standard when the snapshot is taken at month end. That would mean the end of month picture was not representative of the true patient experience.”

In fact it does not matter whether the snapshot is taken monthly or weekly, because the provider still has to treat the same patients during the month to achieve the standard when the month-end snapshot is taken. So there is no genuine incentive for providers to behave in this way.

Counter argument 2: “Data quality is poor for waiting list snapshots, but pretty good for activity. So sanctions can be more accurately applied by counting long waiters as they are treated.”

The premise about data quality is absolutely correct. But perverse sanctions applied to better quality data are only doing the wrong thing righter.

And when waiting list data is inaccurate it usually shows too many patients, not too few (as the current national waiting list validation exercise across around 60 providers suggests).

Incomplete pathway sanctions provide a valuable incentive to having well validated waiting lists, particularly for longer waiters.

Counter argument 3: “Trusts shouldn’t have had those long waiters in the first place, so the penalty is fair no matter when we count them.”

No it isn’t.

The thresholds on the standards mean that the perverse admitted sanctions kick in first, so hospitals are preferentially punished for treating long waiting patients, rather than keeping them waiting.

We saw above how the financial burden already falls more heavily on trusts that treat their long waiters than on those that keep them waiting.

Counter argument 4: “There is more scope for gaming waiting list based targets.”

It is true that some hospitals deliberately delay validating their waiting list patients until they reach 18 weeks, to flatter the denominator on the 92 per cent target.

But it is also true that some hospitals deliberately admit nine short waiters for every one long waiter (“9:1 quota management”) to guarantee achievement of the 90 per cent target - even worse, the admitted sanctions directly encourage them to do so.

Admitted and non-admitted statistics should continue to be monitored as a cross-check, but that does not require heavy sanctions to go with them.

Counter argument 5: “The incomplete pathways standard is looser than the admitted standard, so it would lengthen waiting times if we relaxed sanctions against the admitted standard.”

The premise is correct.

But first, it would only lengthen waiting times by up to around two weeks, which is well within recent variability on waiting times.

Second, patients currently get stranded the wrong side of 18 weeks because the sanctions push trusts into 9:1 quota management, which limits their capacity to admit long waiting patients.

So minimising the admitted and non-admitted sanctions would greatly shorten waits for some patients and make the waiting list fairer.

Counter argument 6: “We’re going to clear the long wait backlog in the short term, so that the perverse sanctions won’t apply thereafter.”

It sounds an attractive proposition, and Mr Hunt made this argument on the 4 August: if backlogs can be cleared so that very few patients are waiting longer than 18 weeks, then none of the sanctions would apply and the perversity would be removed.

However, this happy position would need to be achieved in every subspecialty waiting list in every trust before the perverse incentives were eliminated, and there is no prospect of that happening in the foreseeable future.

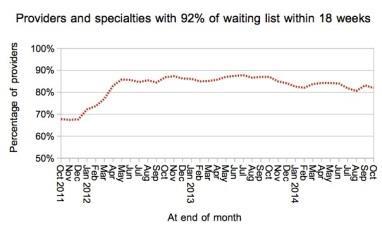

Even when waiting times were at their best (between the introduction of the incomplete pathways sanctions in April 2012 and the size of list passing 2.9 million in summer 2013) more than 10 per cent of trust- specialties were still breaching the incomplete pathways standard.

In conclusion, the arguments in favour of retaining the admitted and non-admitted sanctions amount to little, and are heavily outweighed by the perverse incentives they create.

Should patient tracking lists be collected?

The stated aim of collecting weekly patient tracking lists, or PTLs, is to “ensure that accurate data to support the management of patients waiting for treatment is available at both local and national levels”.

This is portrayed as the continuation of existing temporary arrangements, but it is not, because there is a new requirement to reconcile the data with the referral to treatment returns.

‘The large information burden on providers isn’t warranted’

I do not know what exactly is currently being submitted because the data is not published, and the vague expression “PTL” can mean anything from “the waiting list” to “the patients we need to treat this month”.

But this requirement would impose a large information burden on providers and it would be worth considering carefully whether this is warranted. I suggest it probably isn’t.

If there is appetite to impose an information burden of this scale, there are other things that could be more usefully collected instead. For instance, monthly data on other kinds of waiting list movement, at the same provider specialty level as the existing RTT submissions:

- additions to the list (clock starts);

- removals not picked up in the admitted and non-admitted data; and

- how many admitted and non-admitted patients were “two week wait” and “other urgent”.

Together with the existing data, this would provide enough data to model RTT activity and waiting times into the future under a range of scenarios.

It would also allow checks for data consistency, and providers could be incentivised to ensure that additions = treatments + other removals + growth in waiting list. (Similar cross-checkable data used to be collected in the old Körner returns, though accuracy was not incentivised and data errors became accepted.)

Specific changes suggested

My specific proposals for amending the draft NHS Contract 2015-16 are as follows.

1) The balance of 18 weeks sanctions

In Schedule 4, A: Operational Standards, the sanctions for the admitted (E.B.1) and non-admitted (E.B.2) standards should be reduced as much as possible, and the sanctions for incomplete pathways breaches (E.B.3) raised. This can be achieved while maintaining the overall financial burden at the desired level.

For instance, based on published figures for April-October 2014, if the admitted and non-admitted sanctions were lowered to £50 per excess patient, and the incomplete pathways sanction raised to £270 per excess patient, the overall burden of sanctions would be almost unchanged but the perverse incentives would be greatly diminished.

Ideally, though, the sanctions for admitted and non-admitted breaches would be reduced to zero to completely remove the perverse incentives (data would continue to be collected on all standards).

This would have the added benefit of greatly simplifying the sanctions, both by reducing the number of sanctioned standards, and by making redundant the complex provisions for clock pauses which only apply to the adjusted admitted standard.

At a roughly constant overall financial burden, the sole 18 weeks sanction would then be £300 for each excess incomplete pathways breach.

2) Perverse sanctions should be subject to commissioner discretion

If the admitted and non-admitted sanctions are higher than zero, then commissioners should have discretion to waive them in defined circumstances where they judge that all of the following conditions are being addressed to their satisfaction:

- the commissioner has authorised the admitted and/or non-admitted breach before it occurs;

- the provider has viable plans to shrink the waiting list to a size where all the 18 week standards are safely sustainable, and then to maintain it below that size thereafter;

- the provider can demonstrate that those plans allow adequate capacity for clinically urgent patients to be treated sufficiently quickly;

- the provider can demonstrate that their patient scheduling processes protect clinically urgent patients, and schedule routine patients broadly in chronological order; and

- the provider can demonstrate that their waiting lists are continuously validated and their waiting list data is accurate and consistent with other waiting list movement data.

In Schedule 4, A: Operational Standards, this could be taken in under both E.B.1 and E.B.2 by changing the “Consequence of breach” wording to read: “Where the number of breaches in the month exceeds the tolerance permitted by the threshold, and where the relevant Commissioner has not agreed in advance both the breach and the provider’s plans for achieving and safely sustaining the standard, £[ ] in respect of each excess breach above that threshold.”

3) Drop the requirement to submit cross-checkable PTLs

On Particulars page 50, omit the proposed new requirement to have “Consistency between weekly 18 weeks PTL return and monthly RTT return”, and in any other guidance allow those weekly PTL submissions to cease.

Rob Findlay is founder of Gooroo Ltd and a specialist in waiting time dynamics

6 Readers' comments