Introducing innovative ways of working is becoming more important to the NHS day by day, says Chris Loughlan, but we must look at non-linear methods to promote it

The nature of innovation in the NHS needs a different model. There is some empirical evidence and there are also robust theoretical arguments for building strong links between different parts of the innovation system.

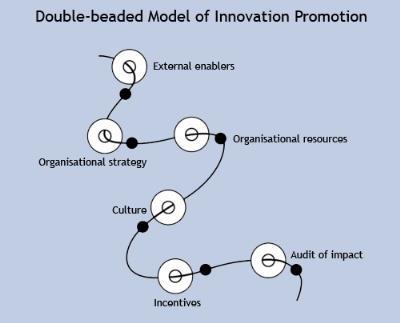

The “double-beaded” model (see figure 1 below) depicts four pivotal features for sustained innovation:

- alignment;

- additive;

- dynamic; and

- non-linear.

The larger bead in the diagram represents the wider systems and processes of innovation, while the small dark bead represents people working in or for specific innovation programmes or projects within any one organisation.

Figure 1

The chances of successful implementation are heightened if the people and projects become aligned with one another in the purpose and specific direction. Staff can therefore access respective resources, networks and, most importantly, work towards similar performance/outcome metrics.

‘NHS trusts with an innovation strategy consistently outperformed NHS trusts without one’

As a direct result of better alignment, the “additive nature” of innovation processes can be realised through synergy of effort. This additive element becomes a key feature in appraisal of scale (specific groups of NHS staff) and scope (levels of NHS organisations) of the implementation.

Innovation cannot be construed as a single event or entity, indeed it is characterised as involving teams of staff − more often a collective achievement spanning public and private dimensions.

The dynamic nature of innovation is also due to the fact that during the time lag from invention to innovation, a combination of several factors including knowledge, skills and resources need to come together or be brought together.

Many innovations are the result of a series of intra-related smaller innovations which often reside external to any one NHS organisation.

Scale and scope

The need to bring together external knowledge, skills and resources may not be apparent to the organisation or indeed to the individuals in question. Therefore, the latent nature of innovation highlights the fourth feature in this model, the non-linear aspect of implementation.

Individuals will need to recognise the fact they will have to work “back and forth” within and across organisations. Hence, the dark beads can slip between the larger organisational bead framework.

While innovation can be looked at, first, to implement a change in a new context (ie: innovation stemming from adaptation), the level can subtlety change from “marginal” innovation to “incremental” and then through to “radical innovation” at both the scale and scope.

‘The overriding consideration is people still want to feel that their work is valued: they have a purpose’

For changes in the level of implementation to be realised, there needs to be the facility of incremental feedback loops within and across the NHS health economy.

Therefore the “back and forth” elements within the model typify the need for individuals to work in a circuitous fashion in a range of networks external to any one organisation.

The key elements of promoting innovation at an organisation include:

Strategy

The importance of an innovation strategy was reinforced by a recent review which found that NHS trusts with a strategy consistently outperformed NHS trusts without on all four major innovation indices: activity, capability, impact and engaging with external conditions.

One of the critical features of an organisational strategy will be the detailing of an explicit or assumed heuristic framework to underpin future investment and activities in innovation.

Figure 1 lists a number of ways of “looking at” or ”finding a way in” to promote innovation. Such a framework may help to appreciate the boundaries between a purely systems-based approach and one that primarily looks at individual behaviours. It may help to re-enforce the need for an organisational strategy to elicit strands of thinking from each perspective.

Leadership

While innovation is part of everyone’s business and indeed the concept of open innovation is predicated on the notion that we cannot safely assume where good ideas will spring from, an organisation will require a member of the senior management team to take the lead for promotion.

Those responsible will be in a position to monitor, review and evaluate the outcomes and impact from implementation of the innovation strategy.

A route map

The innovation terrain in the NHS is rather complicated, with a range of organisations offering support at different levels of idea formulation, development and implementation.

This terrain is not assisted by the lack of clarity as to the meaning of innovation across the multitude of NHS staff groupings. The design and production of a regional innovation route map would provide a visible means for navigating this terrain and provide NHS staff with a single point of contact for information and advice.

Innovation scouts

An “innovation scout” has an organisational-wide remit to identify and support ideas that have the potential to add benefit to the service. In the east of England, Health Enterprise East (an NHS innovation hub) has developed an infrastructure in which an innovation scout has been nominated in the majority of NHS organisations in the eastern region.

‘“There is no alternative” to innovation seems to becoming truer for the NHS on a daily basis’

These scouts adopt a dual role of identifying and presenting evidenced-based innovations from elsewhere for adoption and diffusion within their own organisation and, identifying new innovations generated by their own organisations staff for review and development.

The introduction of competent scouts will reduce the risk of investing time and effort in ideas which are not feasible, ethical and cost-effective. An innovation scout could be a shared resource at a sub-regional health economy level.

Incentives

Literature from health promotion has provided evidence that in relation to staff retention, the three most common characteristics listed are: making a contribution, being valued for that contribution and job security.

One might argue the case that in today’s climate the order of these characteristics may change somewhat, but the overriding consideration is people still want to feel that their work is valued: they have a purpose. Notwithstanding an appeal to a utilitarian ideal, innovation activity could be linked to a series of incremental incentives.

NHS staff who contribute to the pool of intellectual property gain recognition and financial recompense for their efforts. In a similar vein, incentivisation could include a proviso whereby staff and departments who contribute to an innovation which brings about significant financial benefit gain some share of this outcome.

An innovation audit

An “innovation audit” based on a checklist of activities and outputs could be one simple method by which an organisation could report on progress achieved through investment in innovation.

The regional health authorities were mandated to produce an annual report on achievement and impact, and would therefore be able to provide the basis of a simple benchmark reference.

The audit would also help to re-enforce the fact that innovation is a core activity of the organisation and that tangible progress was being achieved beyond the rhetoric of policy and production of strategy.

Summary

Promotion of innovation involves a coherent, concerted and systematic effort to achieve stated objectives. An understanding of the nature of innovation adoption and diffusion coupled with an awareness of “open innovation” will bring about a necessary characteristic of flexibility on the one hand and guard against taking an overly mechanistic understanding and application of innovation promotion on the other.

There will always be some measure of risk from this activity, but these risks can be mitigated by having a clear strategy, strong leadership and competent staff responsible for promoting innovation.

Idea generation and innovation are sustainable goods. It is to be hoped that the forthcoming review of innovation in the NHS by the Department of Health underlines this fundamental concept.

The world of the NHS is particularly renowned for its acronyms. TINA (“there is no alternative”) to innovation seems to becoming truer for the NHS on a daily basis.

Find out more

Chris Loughlan is a director at Cambridge Institute for Research, Education and Management, christopher@cirem.co.uk

No comments yet