Despite clear strengths in basic research and discovery, the UK struggles to translate innovation into clinical outcomes. The University Hospital Association and Boston Consulting Group explore how university hospitals can bridge this gap and deliver transformative benefits to patients, the NHS, and society more broadly.

Sponsored and written by

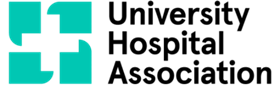

A £78bn opportunity

The UK has one of the strongest healthcare research ecosystems in the world, powered by its universities and research institutes. Yet this strength is not always translated to patient impact – an area where NHS trusts, and university hospitals in particular, play a critical role.

Beyond patient impact, healthcare innovation is critical for the UK’s economic competitiveness. Based on BCG analysis, if the UK were to match the growth of international peers across the healthcare sector, GDP could be ~£78bn (76 per cent) greater than the projected baseline by 2030, indicating significant untapped potential (see Exhibit 1).

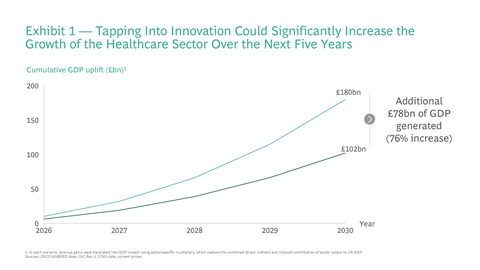

To understand why this potential isn’t being realised, it is necessary to examine the UK’s position across the innovation pathway (see Exhibit 2): identifying areas of strength, diagnosing the barriers that currently limit progress, and setting out how these can be overcome. This article explores each of these in turn and outlines the key role university hospitals have to play.

The UK’s healthcare innovation paradox

Despite the UK’s global standing as a leader in healthcare research (fourth globally in the Nature Index) and its attractiveness for early-stage investment (third-highest healthcare venture capital investment according to BCG analyses), it struggles to translate this into clinical outcomes and patient benefits.

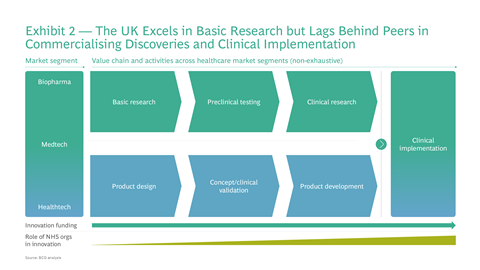

This “translational gap” is reflected in:

- The UK’s clinical trial levels relative to peer nations, slipping from third to fifth globally since 2015 (Association of the British Pharmaceutical Industry data); see Exhibit 3

- The slower commercial scale-up of successful life science innovations; only 3 per cent of UK healthcare startups reached late-stage venture funding, compared with 6 per cent in the US and 4 per cent globally (BCG analysis)

- The relatively limited access to new medicines compared to peer nations; only 65 per cent of new EU-approved medicines were available in England between 2020 and 2023, compared with 90 per cent in Germany and 83 per cent in Italy (IQVIA)

University hospitals will need to play a central role for the UK to close this gap. Despite only accounting for around 20 per cent of NHS trusts, National Institute for Health and Care Research and NHS Confederation data show that university hospitals deliver more than 50 per cent of NIHR-funded clinical trials and treat a disproportionate share of patients (~35 per cent). Yet university hospitals remain a misused and overburdened asset, with signs of weakening innovation capabilities. For example, over the past decade, the proportion of clinical academics has fallen by 14 per cent, with junior grades of academics declining by 40 per cent (Medical Schools Council).

Barriers limiting innovation across the NHS

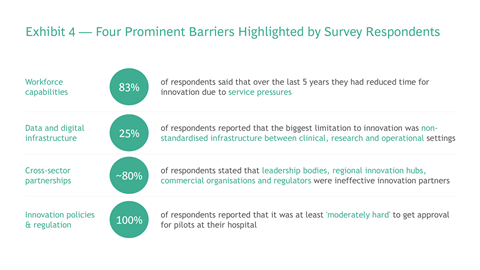

To understand these challenges, we surveyed senior executives of the University Hospital Association (UHA). Their responses underline the systemic pressures holding back translational innovation: workforce pressures, fragmented data systems, weak partnerships, and slow regulatory pathways (see Exhibit 4).

- Workforce capabilities: Limited capacity and capabilities were among the most frequently cited barriers to innovation, with 83 per cent of responses highlighting limited time for innovation due to service pressures as the biggest constraint. Few reported structured career pathways for clinician-innovators: only 3 per cent said that the clinical entrepreneurship programme was a strength of their hospital.

- Data and digital infrastructure: Fragmented systems and inconsistent data-sharing across trusts hinder translational innovation. Survey respondents pointed to non-standardised digital infrastructure (25 per cent of responses), insufficient computer capacity (25 per cent), and fragmented IT systems (17 per cent) as the biggest barriers. External innovators also face restricted access to data, slowing the generation of real-world evidence and limiting validation of new tools.

- Cross-sector partnerships: Forming effective partnerships with the NHS demands high upfront costs and the ability to navigate opaque processes. The case of multi-cancer early detection tests illustrates this. Only GRAIL’s Galleri test has secured a large-scale NHS collaboration, doing so by self-funding a £150m, 140,000-patient trial and building a dedicated UK testing facility. Other credible developers, such as Freenome and Thrive, have not been able to replicate this level of investment, limiting their ability to enter the system despite strong credentials.

- Innovation policies and regulation: Regulatory frameworks remain slow and restrictive, delaying patient access to novel technologies. For example, AI-assisted physiotherapy tools often face a 36-month-long National Institute for Health and Care Excellence evaluation process, compared to US Food and Drug Administration timelines of six to 24 months. All survey respondents said pilot approval is at least “moderately hard” in their hospital.

These barriers hold back university hospitals from realising their full potential. Overcoming them will be critical to improving outcomes for patients and the NHS.

How university hospitals can foster innovation

The barriers mentioned can be addressed through three broad solution areas, and university hospitals have a key role to play across all of these.

Strengthen the NHS as an innovation platform

- Construct and drive a pipeline from innovation to impact. The NHS must treat innovation as a strategic priority, with clear goals, milestones, and funding structures. University hospitals should drive this change by embedding innovation into long-term strategies. Singapore’s National University Health System offers a strong example. Its Practice-Changing Innovations (PCI) programme has committed to delivering six innovations by 2030, with every candidate project assessed by an international expert panel and funded against defined milestones. More than 100 ideas have already been reviewed, with nine receiving multi-year backing, demonstrating how a clear strategy and structured processes can focus resources on the innovations most likely to scale.

- Enable the workforce. The NHS’s workforce needs both the capacity and the capability to adopt new approaches. University hospitals can reverse the decline in clinical academics by expanding roles and providing clinicians with protected innovation/research time, while also embedding digital and AI skills into training.

- Unlock the potential of data. Data is the lifeblood of innovation. University hospitals can lead the deployment and effective use of initiatives such as the Federated Data Platform (FDP) and Health Data Research Service (HDRS) to improve interoperability across trusts, enable secure data sharing, and generate real-world evidence to validate new tools.

A clear strategy and approach, skilled staff, and robust data create the foundations, but they are not enough. Innovation also depends on effective collaboration across the sector.

Facilitate partnerships and cross-sector collaboration

- Establish single points of contact to coordinate partnerships. University hospitals should serve as defined coordination points within the NHS. Establishing both physical and digital hubs, integrated with care delivery organisations, can bring together academia, industry, and the NHS to establish partnerships to accelerate innovative programmes.

- Supercharge collaboration with a diversity of funding and expertise. Coordination hubs are far more effective when they attract a mix of partners who can contribute not just funding but also the right expertise. Private sector investors and venture partners often bring additional rigour and experience in growing companies, while the NHS provides access to clinicians, patients, data, and routes to adoption. Blending these perspectives helps move promising technologies beyond pilots into wider clinical use. King’s Health Partners has shown how this can work, in collaboration with leading venture investors such as General Catalyst and Speedinvest. Through Meridian Ventures, it created the UK’s first NHS-anchored venture capital fund, raising ~£38m to support clinical innovation.

Even with stronger partnerships, progress will stall unless the incentives and regulatory environment encourage innovation to scale.

Incentivise healthcare innovation with effective policy and regulation

- Strengthen incentives. University hospitals can pioneer approaches to effective intellectual property frameworks, co-investment models, and incentives that reward clinician innovators, reducing barriers to participation and ensuring benefits are shared. The Department of Health and Social Care could consider similar concepts to incentivise system-wide innovation, eg, research and development tax incentives.

- Create the right testing environments. As natural testbeds, university hospitals can collaborate with NICE and the Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency to expand regulatory sandboxes to safely test emerging technologies and solutions.

- Streamline regulatory frameworks. While university hospitals have a limited direct regulatory role, they can accelerate compliance with existing frameworks by improving the processes that contribute to evidence generation. They can also act to collectively highlight where current frameworks create unnecessary delays and advocate for pragmatic reforms.

Taken together, these actions would position university hospitals not just as centres of research and care, but as engines of innovation.

Conclusion

The UK faces clear risks if it continues to lag in translational healthcare innovation: slower access to effective treatments for patients, rising NHS pressures, and lost competitiveness in the global life sciences sector.

We propose that university hospitals leverage their position as NHS leaders with a “Translation Compact”, coordinated by the UHA. The compact would align university hospitals to three priorities:

- Enable the workforce by training more clinical academics, expanding roles and providing protected time for innovation.

- Foster partnerships by working with industry in a more structured and consistent way, with clear entry points, streamlined processes and shared infrastructure.

- Strengthen incentives for individuals and organisations by setting competitive policies, encouraging clinician-innovators and rewarding contributions.

Other actors must also play their part: DHSC should set long-term national priorities, align funding, and accelerate data infrastructure programmes. Regulators such as NICE and MHRA should streamline approval and evidence-generation pathways. Industry and academia must continue to contribute investment, talent, and expertise.

If implemented, these efforts would allow the UK to shift from being a world leader in discovery to a world leader in translational innovation. This could have a transformative impact: reducing NHS costs, unlocking productivity gains and improving outcomes for millions of patients.

Special thanks to Chris Fassnidge, Raoul Ruparel, Ritvij Singh, Hadley Copeland and Erika Williams.