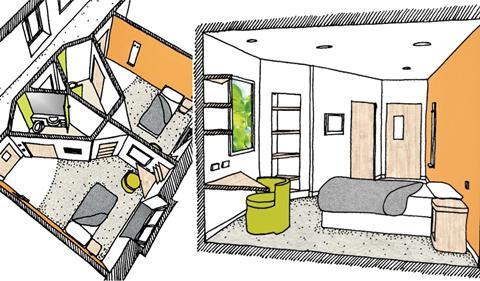

User influence lies behind bedroom design features such as more private storage for possessions, noticeboards that look like pictures – and, crucially, a window seat

Mental Fight Club rooms

“The ability to sit by the window sounds very simple but it is very important. That is the connection out to the world again. That is where you feel safest,” says Sarah Wheeler.

Ms Wheeler, the founder of the Mental Fight Club, a drop-in centre in Southwark, London, is one of the mental health service users that Procure21+ approached to help inform the design for its functional and organic mental health bedrooms.

“Most of us who have been in hospital know the rooms are very drab and basic,” she says. “There’s no thought about what it is like to come into them. I don’t think you can understand what it is like to be in that room unless you have been a patient.”

Over the last six months, Ms Wheeler and other service users have been talking with Procure21+, feeding in their lived experiences at all stages of the design process. This part of the process has been critical to the end scheme, says Procure21+ core team architect for Procure21+ Rosemary Jenssen.

“There have been small comments that have been gems. We have been lucky enough to be able to capture that and can now share it nationally. We want to open the eyes of trusts to what is possible.”

‘The group went through the exercise of quantifying precisely how much shelving and wardrobe space is required’

One point to emerge repeatedly in discussions with service users was that typically trusts provide too much storage space. For those with very little, this unfilled space was seen as oppressive, leaving them thinking: “What does this room say about me?

“We found trusts very rarely briefed the architects about the amount of storage required,” says Ms Jenssen. The group went through the exercise of quantifying precisely how much shelving and wardrobe space is required in a short-stay room, and realised that trusts were often over providing in this area.

On display

Another comment from a service user about always having to have intimate possessions or clothes on full display, as typically all storage areas are open and facing outwards, has led to the team including some sideways-facing shelving to give a measure of privacy and restore some sense of control to occupants.

In the same spirit of not wishing to intimidate patients, a desk area has been developed not to look overtly like a work space, although it can be employed as such. Alternatively, it can be used as a dressing table, or utilised as a space where clothes can be laid out.

Likewise, a noticeboard above the desk and visible from the bed is now not the usual blank, white, overwhelming space if left unadorned by an occupant. Choosing a scene from nature as the background is a simple touch, but it is these small things that are being found to make a difference.

User engagement

What was of particular importance during the design process, notes Ms Jenssen, was exploring different ways of engaging with service users. With the help of the Mental Fight Club, meetings were held at its Dragon Cafe and were well attended and successful.

‘The resulting rooms are a massive improvement on what is available, and feel “more like an affordable hotel than a prison”’

Service users were invited to comment on a series of free hand sketches envisaging the bedrooms from the occupant’s perspective. In the later stages of the consultation, an interactive 1:6 scale model of the bedrooms, complete with artist’s wooden figures, helped draw out any design hiccups.

“The penny dropped during this session,” notes Ms Jenssen, “We had almost tried to over design from an aesthetic point of view. The service users came up with different positions for the furniture to make it feel more homely.”

The resulting rooms, says Ms Wheeler, are a massive improvement on what is available, and feel “more like an affordable hotel than a prison”. Most importantly, she says, they bear clearly the imprint of feedback from service users.

Both the rooms, which are Health Building Note compliant, are en-suite, another factor that was highlighted as important by service users. The footprint of the functional room (combined bedroom and en-suite) is 15sqm; the organic room, where users are more likely to need assistance, is 18.1sqm, and is larger both within the bedroom and the en-suite.

A recent technical workshop, in which the rooms were physically tested out, highlighted the need for this more generous sizing.

It ensures that there is room for two staff members to help an occupant, plus space for any required standing aids, and gives consideration to the increasing size of the population. “In terms of the physical room itself,” says Ms Jenssen, “I think it is absolutely future proof.”

The over-arching idea of the repeatable rooms and standardised components, she explains, is that one size fits all in terms of the physical dimensions and the proportions of the rooms, but that then there are a number of arrangement options for bed position, furniture alternatives, and a window seat that trusts can choose from, or adapt to meet their local needs.

‘If you could pick the room up and shake it, the things that would fall out are those that trusts can make local decisions over’

If you could pick the room up and shake it, she says, the things that would fall out are those that trusts can make local decisions over.

Recognising that different trusts have different policies, beds can either be against two walls or in a peninsula position, allowing clinicians access from both sides of the bed. Both bed positions enable a clear sightline to the door, as well as to the bathroom.

Each room incorporates the ability to sit by the window. In the functional design there is the opportunity for trusts to select a window seat; with the organic room there is the possibility of a bay window, where a high-backed chair or wheelchair can be placed.

‘Looking out, getting a sense of the outside world, of nature, and the seasons and time passing is incredibly important’

This, agrees Procure21+’s healthcare planner Stephanie Brada, is a very humanising feature.

“We are encouraging people to focus at the window,” she says. “It’s dramatic the difference if people sit near a window. “Looking out, getting a sense of the outside world, of nature, and the seasons and time passing is incredibly important.

She concurs that the extensive engagement with service users has been the critical factor in influencing the final designs. “It is the little things we have learnt about that can make a difference. The devil is always in the detail,” she says. “We have brought the voice of service users into the process.”

“When people walk in to a mental health bedroom, they need a sense that they are being looked after as an individual, not being stripped of their identity.

“Service users told us that they ask: ‘Where am I in this room? Who am I? Am I worth it?’

Zoning of space

Ms Brada points to another design feature that was gleaned from interaction with service users - the zoning of the rooms into public and private spaces which echo those found within the home.

“The layout of the mental health bedrooms gives service users cues for different spaces,” she explains. “As soon as you open the door there is a sense of entering a personal space. When you walk in, there is a threshold. Over towards the window there is more of a private area.”

The threshold provides a space where visitors and clinicians can wait to be invited into the room, as well as incorporating a piece of furniture designed like a traditional hall-stand, where outer wear can be placed.

Past the threshold, which has vinyl flooring, there is carpet in the bedroom zone of the functional room. This signals a private space, provides comfort and benefits the acoustics (another critical factor in mental health rooms).

“We are trying to give service users back a sense of control,” says Ms Jenssen. “We have tried to avoid the rooms going to the lowest common denominator from a risk averse point of view. Hopefully, what we have designed is a room that is therapeutic in terms of space and comfort while minimising the risk of harm.”

Procure21+ is working with various manufacturers to improve the design of many common components. For example, says Ms Jenssen, “There is a shortage of aesthetically-pleasing, robust and anti-ligature light fittings.”

‘What would be valuable to see is an evaluation of the effect of these rooms on the incidence of violence, aggression, self-harm or reliance on medication’

The framework is also involved in developing a sliding anti-ligature pocket door to replace the HBN-required lock-back door, which is designed with suicide prevention in mind, but is bulky and has a custodial impact on the room.

Looking ahead, and considering the paucity of robust evidence around therapeutic design in mental health settings, Ms Jenssen is keen to carry out post-occupancy assessments of the rooms. What would be valuable to see, she says, is an evaluation of the effect of these rooms on the incidence of violence, aggression, self-harm or reliance on medication.

With this in place, the mental health repeatable rooms will have the best of both worlds - rooted firmly in the evidence base and bearing the stamp of approval from service users. l

Mental health supplement: ‘The rooms are part of the therapy’

Designing a future proof mental health hospital room

- 1

Currently

reading

Currently

reading

Mental health supplement: Case studies in room design

No comments yet