An HSJ/KPMG poll about the future vision for the NHS suggests some optimism about developing new care models but health service leaders are clearly dubious that they will ever get the investment they need to deliver real transformation. By Jennifer Trueland

At the launch of the NHS Five Year Forward View in October, NHS England chief executive Simon Stevens said that the health service was at a crossroads. The NHS needed to change substantially to secure the future, he said, and as a country we needed to decide which way to go.

There has been a lot of goodwill towards the forward view with even the government responding positively and promising more cash.

‘There has been a lot of goodwill towards the forward view’

But is this positive feeling felt across the service or do NHS leaders on the ground fear that it is another case of a vision that is not backed by substance?

These are some of the questions that HSJ readers were asked in a survey run in association with KPMG.

We sought to find out whether readers felt their local healthcare systems were prepared for the new world of the forward view, whether they felt that the required resources would be forthcoming, and what the barriers to change were.

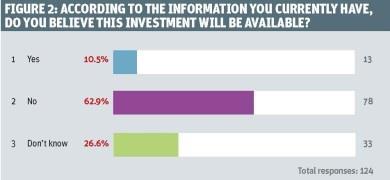

The results show a mixed picture. There is some despair - for example, more than six in 10 respondents were not confident that their locality would get the upfront investment needed to make the service model changes they wanted to (figure 2).

‘Most people in healthcare have been trained to manage delivery of healthcare, not transformation of it’

But there was also optimism, with two-thirds of respondents feeling that their locality could be a vanguard site for new models of care outlined in the forward view.

Senior managers are arguably under the most pressure to make sure that the necessary change takes place. But are they up to the job?

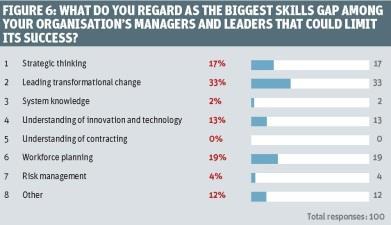

Asked about the biggest skills gaps among their organisation’s managers and leaders that could limit success (figure 6), around a third (33 per cent) cited “leading transformational change”.

Almost one in five (19 per cent) cited a skills gap in workforce planning, while strategic thinking was seen as the biggest gap by 17 per cent of respondents.

This comes as no surprise to Jennifer Dixon, chief executive of the Health Foundation. Writing in HSJ shortly after the launch of the forward view, she called for support for manager and clinician leaders to help them drive through major transformational change, and for people on the frontline to be given formal quality improvement skills.

In response to the survey results, she concedes that there is a way to go. “Yes these are gaps; we have the leaders for today’s system not tomorrow’s,” she says.

“The way forward? I would favour two things. First, allow local leaders more flexibility from existing rules to make local changes… Second, national leaders and arm’s length bodies should model the desired behaviours and back local efforts much more overtly. The forward view is a great framework but only a framework.”

Andrew Hine, UK head of public sector and healthcare for KPMG, agrees that there is a skills gap in leading transformational change. “Most people in healthcare have been trained to manage delivery of healthcare, and not the transformation of it,” he says. “They’ve been trained to squeeze a few extra per cent of improvement out of a static system rather than ask ‘should it be like this?’ They need to have the time and space to, for example, look at international systems that don’t bring as many people into hospitals. There are multiple brilliant things about the NHS but it needs to learn from other, more dynamic systems.”

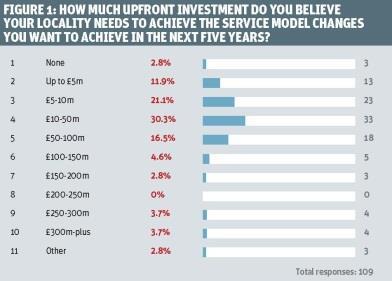

However upskilled your leaders, money will always be an issue. Respondents differed over the amount of money they thought their locality would need to implement the service models they wanted to achieve (figure 1).

While just 2.8 per cent said they would need none, at the other end of the spectrum, 3.7 per cent said they would need £250m to £300m, while the same proportion wanted £300m-plus. By far the biggest proportion (30.3 per cent) said that they would need £10m to £50m, while 21.1 per cent said £5m to £10m and for 16.5 per cent the magic number would be somewhere between £50m and £100m.

‘Cutting agency spend is a “tip of the iceberg” issue. The real challenge is effecting real service redesign’

There was more agreement on whether respondents felt the extra cash would be forthcoming, with just 10.5 per cent saying they thought it would, as opposed to the 62.9 per cent who did not (with the remainder being “do not knows”).

Mark Britnell, global chair for healthcare for KPMG and a former NHS trust chief executive, says the findings indicate that a transformation fund of some £2bn is needed. But money alone will not be enough. “Most leaders in healthcare environments are transactional, rather than transformational,” he says. “We need to move from ‘doing things better’ to ‘doing better things’.”

From the perspective of his global role, Mr Britnell points out that the challenges faced in England are similar to those elsewhere in the world, but adds that the necessity of making efficiency savings moves that level of challenge up a notch.

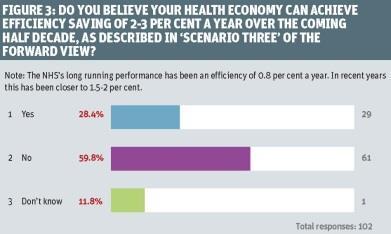

The forward view outlines a number of scenarios around efficiency savings. One scenario involves health economies achieving efficiency savings of 2-3 per cent in the next half decade. Asked whether this could be achieved, almost six in 10 (59.8 per cent) in our survey said no, while 28.4 per cent believed it could, and the remainder did not know (figure 3).

Asked what would be the biggest focus for increasing efficiency savings in the next two years, just over a third (34.8 per cent) said cutting spend on agency staff, while the same number said it would be investing in social care provision to reduce the number of social admissions. Mr Britnell says it is worrying that there was so much focus on cutting agency spend because this is a “tip of the iceberg” issue. The real challenge is effecting real service redesign and improvement, he says.

So what models do respondents believe will be the most prevalent in driving service transformation? Presented with a menu of options, respondents scored Primary and Acute Care Systems (PACS) and Urgent and Enhanced Emergency Care Networks well overall, with 27.8 per cent and 21.9 per cent respectively saying they would be dominant models. A strong majority (72.4 per cent) felt that enhanced health services in care homes would either be a dominant model or used quite widely.

Specialist franchises and hospital provider chains were the least popular options: 42.2 per cent and 32 per cent respectively said these models would not be used at all.

‘It will take a while to agree on exactly how to effectively achieve integration’

Many respondents gave examples of how they could lead the way in implementing new care models. Asked to provide brief details of their locality’s plan, there was a strong flavour of the value of collaboration and integration. Ideas included an integrated emergency centre, with primary care integrated with accident and emergency; a provider alliance holding a pooled budget and managing nine services; and bringing four clinical commissioning groups, three local authorities, one acute and one community mental health provider together to form a coherent system with an ambulance trust as a key partner.

Zara Hyde Peters, programme director of health and wellbeing for Birmingham Community Healthcare Trust, welcomes this finding. “There does appear to be a strong recognition particularly among all care providers and CCGs that the integrated care agenda is the way to go, which is a view I would support,” says Ms Hyde Peters, a member of the NHS Leadership Academy Executive Fast-Track programme.

“However, it will take a while to agree on exactly how to effectively achieve this integration. It is good that the will is there, although the broader message of empowering individuals to manage their health and wellbeing in their communities needs to get through.” She added that finding examples of effective integration to learn from was very important to bring the integrated care agenda to life.

There was a mixed picture when respondents were asked (on a scale of one to 10) how confident they were in commissioners and providers in their area to plan and begin implementing the necessary strategic and organisational change in the coming financial year. More than one in 10 (11.3 per cent) had the lowest possible confidence, scoring one, while 6.6 per cent said two and 18.9 per cent rated their confidence level at a three. Just 5.7 per cent were extremely confident, rating it at 10 out of 10, while 4.7 per cent and 15.1 per cent scored confidence at nine or eight respectively.

Asked how confident they were in commissioners and providers to do this in the next five years, and the picture was much more positive, with the majority scoring it at six or above. Just 5.8 per cent gave the lowest rating, while 14.4 per cent rated their confidence level at 10 out of 10.

Mr Hine admits he “raised a quizzical eyebrow” at these particular responses. “The system has got a long way to go to skill up to do the big transformation that is necessary,” he says. “That around a quarter of people are confident or very confident doesn’t square with what I’m seeing.”

He has sympathy for those who feel there are barriers to transformation. “Transformation is something that is rarely done in healthcare, certainly in healthcare in the UK,” explains Mr Hine. “We haven’t got a system that incentivises people to transform services at the interface, particularly between hospitals and the community, and between health and social care.”

“Competing financial interests is a very fair consideration. If an acute hospital chief executive supports a move to community services then that money leaves the budget.”

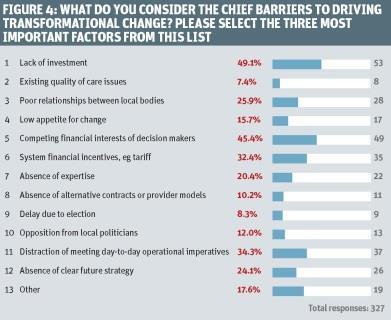

This feeling was backed by respondents. Asked to select the three main barriers to driving transformation, almost half (45.4 per cent) named the competing financial interests of decision makers (figure 4).

Sir Sam Everington, a GP in east London and chair of Tower Hamlets CCG, has some sympathy for that view. “There will always be barriers to change, and it’s always going to be harder when you’re in a difficult financial environment,” he says.

‘We need to move from stick to carrot, provide improvement support for leaders and invest in a transformation fund’

This rings true with Ms Hyde Peters. “It is inevitable that the current fragmented structure will make coherent restructuring more difficult,” she says. “A number of steps can help address this. The new delivery models promoted in the forward view are a start; if the funding mechanisms for care delivery support these new delivery models that will reinforce breaking down some of the existing barriers.”

Clear local health and wellbeing strategies should be a tool for closer local cooperation, she says, although she concedes that the impact to date appears “mixed”.

Respondents also pointed to other barriers to transformation, including financial incentives. Around a third blamed system financial incentives such as the tariff, while a similar number blamed the distraction of meeting day to day operational imperatives.

Nearly a quarter said that absence of a clear future strategy was a key barrier, while 10.2 per cent blamed absence of alternative contracts or provider models.

But what about the reasons for making changes in the first place?

Improving care for patients is clearly a priority. Given a list of incentives for change and asked to choose the three most valuable, almost nine out of 10 (89.7 per cent) named the “opportunity to improve care for patients” (figure 5).

The next most popular factor, chosen by 60.8 per cent of respondents, was the opportunity to future proof services. Around a third (33.7 per cent) thought that the opportunity to reduce costs was one of the top three most valuable incentives, while almost a quarter (24.3 per cent) chose “opportunity to collaborate with colleagues”.

Jeremy Taylor, chief executive of National Voices, welcomes the focus on patients. “What this says is that HSJ readers are overwhelmingly backing the notion that quality, not cost, should be the primary driver of healthcare reform; however, this doesn’t say what people are actually going to do about it.

“It’s also disappointing that there seems to be a relative lack of enthusiasm for collaboration [as an incentive for change], when one of the real issues in healthcare at the moment is a lack of collaboration between different parts of the system.”

‘The burden of regulation is definitely an issue’

The forward view says that Monitor, the NHS Trust Development Authority and NHS England will “create greater alignment between their assessment, reporting and intervention regimes”. At the time the survey was taken, however, this did not seem to have come through, with around two-thirds of respondents (66.3 per cent) saying they had not experienced this at all.

Is this finding a surprise? “No,” says Sir Sam. “The burden of regulation is definitely an issue. One chief executive told me he had about 80 different inspections in a year. There must be a more manageable way.”

Mr Britnell says that the survey’s findings align very clearly with those in the KPMG report Something to Teach, Something to Learn. This too looks at the dilemmas facing providers in a changing environment and considers ways to achieve positive change.

“What I’m hearing from the results of this HSJ survey is a cry for help,” he says simply. “The forward view is a refreshing view but it’s not an action plan. What we need to do is move from stick to carrot, provide improvement support for leaders, and invest in a transformation fund. The responses to this survey make that very clear.”

1 Readers' comment