Research on stroke cases in Scotland suggests low-cost, hospital-based initiatives could transform outcomes for many, write Evin Uzun Jacobson and colleagues

Delays in emergency treatment for stroke victims are taking a significant toll on Britain’s ageing population, the NHS and the UK economy.

Despite improvements made by the government’s detailed stroke strategy, many more stroke victims each year could be treated faster, at relatively low cost, to avoid long-term disabilities, according to research conducted by our team at the Health and Care Infrastructure Research and Innovation Centre.

This could result in significant reduction in the estimated £8.9bn annual cost springing from those cases, attributable mainly to rehabilitation services for victims, to loss of income and productivity, and to increased benefit payments.

Our research suggests acute treatment could be speeded up for large numbers by low-cost, hospital-based initiatives already operating in some areas.

Our study examined all Scottish stroke care cases in 2010, looking at the Scottish Stroke Care Audit (SSCA) national dataset as well as interviewing clinicians who deliver stroke care in Scotland.

If our findings reflect conditions more widely across the UK, they indicate that the NHS could more than double the number of stroke patients receiving time-sensitive, clot-busting emergency treatment (thrombolysis) that can transform outcomes for patients.

To achieve this goal, hospitals would need to be as efficient as the currently best performing hospitals. This could be achieved through straightforward organisational change.

Acute stroke care delivery is challenging and time critical because urgent imaging of the brain (normally a CT scan) is required to identify the patients eligible for clot-busting drug treatment (thrombolysis). These scans are needed to exclude intracranial bleeding or any other abnormality, which would rule out the appropriateness of thrombolysis.

Four hour warning

It is generally accepted thrombolysis should be administered within four-and-a-half hours of a stroke and the earlier the treatment is given the greater the benefit. Four-and-a-half hours is a tight deadline.

The government’s stroke care strategy has addressed this deadline by raising public awareness of stroke symptoms to discourage delay in alerting the emergency services. The NHS has also reorganised stroke services to speed up diagnosis and treatment.

This strategy has improved the quality and speed of care. However, our study of Scotland’s 2010 figures shows only a quarter of ischemic stroke victims reached hospital within four hours of the onset of stroke. So three quarters of those affected were automatically ruled out of the possibility of having what could have been life-transforming thrombolysis.

A study reported in The Lancet Neurology in May raises the possibility of ambulance-based CT scanning to speed up treatment and potentially benefit more patients. However, the barriers to such a transformation are considerable.

CT scanners are expensive, making it challenging to provide ambulance-based, mobile scanning in a cost-effective way.

There is also a danger the prospect of such technical innovation will obscure the considerable opportunities low-tech, low-cost improvements in emergency care for stroke victims - available right now - could offer.

Our research has identified three issues that could be addressed speedily and offer quantifiable benefits.

First, we need to make sure that, where possible, suspected stroke patients are taken to the hospital most likely to provide scanning and thrombolysis.

Some hospitals do lack out-of-hours specialists to interpret the scan, assess risks and benefits of treatment options and prescribe correct treatment in time. Yet, sometimes, ambulances transport suspected stroke patients to hospitals that do not provide thrombolysis, especially out of hours.

Such cases, where vital time is lost, could be avoided by agreeing protocols with the ambulance service, as well as guidance and training for crews. Improved communication with the receiving hospital could also lead to prioritising stroke patients over non-stroke patients for assessment and scanning upon arrival and ensuring that patients can be taken straight to the scanner by the paramedics.

Second, we should improve access for patients to hospitals offering thrombolysis. That means ensuring acute hospitals providing this treatment facility 24/7 are available in all areas.

The existing gaps in service provision are clear from our research in Scotland. We found that, on average, a patient is twice as far from a hospital providing a 24/7 thrombolysis service as from their nearest hospital. So how do we increase the accessibility of 24/7 thrombolysis? A key barrier that can be addressed is the availability of out-of-hours specialists to interpret scans and decide on appropriate treatment.

Developing telestroke support - remote availability of a specialist to assess the patient and read scans - between hospitals could allow many more patients to receive thrombolysis locally. Such services could be provided via the hub and spoke model, where one hospital offers the service to a group of hospitals, or the mesh model, where a group of hospitals share the service provision on a rotational basis.

Third, our research suggests the NHS should aim to double treatment rates for patients who arrive in hospital within the critical period. This could be achieved by all hospitals matching best hospital practice.

Be the best

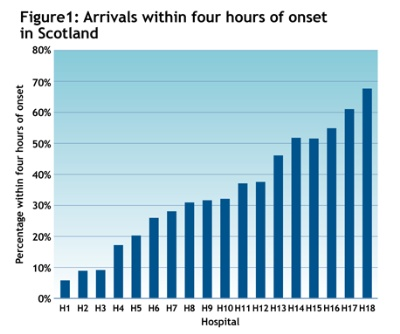

Comparing the 18 hospitals in Scotland that admitted more than 90 per cent of patients arriving within four hours of onset in 2010, we found that, in the best performing hospital, 68 per cent of patients were scanned in time compared with 40 per cent on average - and just 5 per cent in the worst performing hospital (see figure 1).

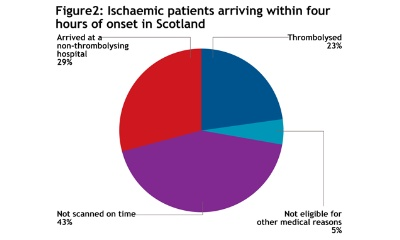

More important, 44 per cent arriving in time were thrombolysed in the best hospital, compared with the 23 per cent thrombolysed on average (see figure 2).

Nationwide, matching up to the best performance could benefit hundreds of people every year.

We do not underestimate the difficulties for individual hospitals of engineering significant changes in the care pathways for emergency care of stroke victims. However, our research suggests a vision of where the NHS could take its next three steps in the stroke care strategy: improving coordination between ambulance services and hospitals; expanding telestroke between hospitals; and optimising scanning and thrombolysis of patients when they arrive on time.

Taken together, these achievable improvements fit an age of austerity in which the NHS seeks to improve quality of care on tight budgets.

Dr Evin Uzun Jacobson and Dr Steffen Bayer are researchers for Imperial College London with the Health and Care Infrastructure Research and Innovation Centre. Dr Mary Joan MacLeod is a consultant stroke physician, senior lecturer at the University of Aberdeen and chair of the audit subgroup of the Scottish Stroke Care Audit.

Find out more

Health and Care Infrastructure Research and Innovation Centre

No comments yet