Staffing is the issue keeping NHS leaders awake at night – and which consumes two-thirds of trusts’ spending. The fortnightly The Ward Round newsletter, by HSJ workforce correspondent Annabelle Collins, ensures you are tuned in to the daily pressures on staff, and the wider trends and policies shaping the workforce.

The workforce plan (yet to be published at the time of writing) is in for a bumpy landing. Plans were set for it to coincide with the NHS’s 75th Birthday, but on a less celebratory note, it will also follow news of the longest-ever junior doctors’ strikes, planned for next month, and a consultants’ strike just a few days after this.

The disruption to patient care will be extreme and there are no signs of a rapprochement between the unions and the government.

The plan’s launch will also follow a stark reminder from the Royal College of Nursing ballot results that almost 100,000 nurses are still keen to strike. Although the ballot’s failure to reach the threshold for strike action will prompt a sigh of relief within Westminster and in hospital trusts throughout the country, it would be foolish to ignore the strength of feeling.

Rishi Sunak has issued platitudes about how the plan will “train, retain, reform and make the most of our talented and experienced staff”, but reports suggesting he might not implement the recommendations of the independent pay review bodies for a 6 per cent public sector pay rise could undermine ambitions to strengthen the workforce. This view is shared by Agenda for Change union insiders I’ve spoken to; they think the fight is far from over and are expecting their members will strike again later this year or early next.

The plan itself – months, and arguably years, overdue – was never going to be a quick fix for the current pay and morale crisis, but it must put an end to piecemeal workforce planning and provide multi-year funding for training and education. Again, reports in the Sunday Times suggesting the plan won’t be funded for more than five years were disappointing and would render it a “fifteen-year plan” in name only.

However, when giving evidence to the covid-19 Inquiry last week, Jeremy Hunt reiterated multiple times the need for the UK “to go further” when it comes to workforce planning, and argued increases in certain staff groups during his time as health secretary did not happen “in the structured way that it should have”.

Mr Hunt said: “I think that we should be better at long-term workforce planning… It takes seven years to train a doctor. It’s never given a higher enough priority in the system, and when a chancellor and a health secretary are negotiating a spending review settlement, they’re thinking about: how are we going to relieve pressure in [accident and emergency] departments this year?”

Perhaps this could be a cause for cautious optimism that the pending plan will receive funding for more than just five years?

One-way traffic

Returning to the morale crisis, the latest General Medical Council State of Medical Education and Practice in the UK report reiterates that the frustration felt by doctors goes far beyond stagnating pay.

The regulator’s research highlighted again that burnout and dissatisfaction are higher than ever among NHS medics, all consequences of rising workloads and pressure to bring down the post-pandemic backlog. Poor support in the workplace, poor working conditions and not feeling valued were also major contributing factors.

The GMC is clear some short-term things can be done to make day-to-day working life immediately better for medics (secure lockers to leave their belongings, access to break rooms, water and healthy food options spring to mind) but it also calls for training roles to be made “more attractive” and warns the drive to tackle waiting lists has resulted in fewer opportunities to train and develop and learn necessary skills – so much so that trainees have reported feeling under-confident in their abilities.

This is clearly unsustainable. But, with continued pressure from the centre to tackle the NHS backlog and no extra staff to pick up the slack, providing trainees with protected time and quality training opportunities feels like a pipe dream.

The report also shows a worrying comparison with last year’s findings; most notably the percentage of doctors “taking hard steps to leave” has risen from 7 per cent to 15 per cent, and the rise in doctors saying they found it hard to provide “sufficient care” to patients from a quarter to 44 per cent.

Another report, this time from the King’s Fund, has also noted the lack of compelling reasons for staff to stay in the NHS, adding it has a “strikingly low number of doctors compared to its peers” and is losing ever more to countries with “better remuneration and working conditions”.

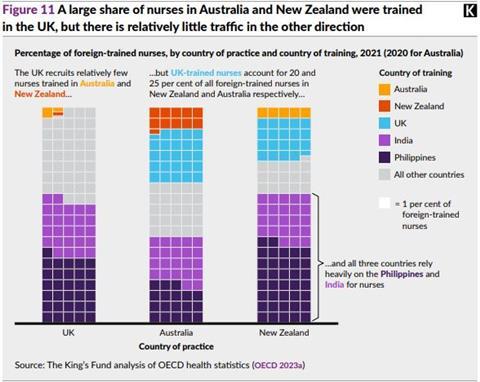

A particularly interesting chart compares where foreign-trained nurses are from in the UK, Australia and New Zealand. It shows that UK-trained nurses account for a fifth and a quarter of the workforce in NZ and Australia respectively, but with the UK recruiting less than 2 per cent of its nurses from Australia and less than 1 per cent from NZ.

The UK is also heavily competing with Australasia when it comes to recruiting nurses from the Philippines and India, on which it continues to be heavily reliant to fill vacancies.

Even with a fully-funded workforce plan, international recruitment will be crucial for years to come and we must – as argued by report author KF chief analyst Siva Anandaciva – learn from other healthcare systems if the NHS is to become more of a leader and less of a laggard.

No comments yet