There is ‘fantastic talent’ to be found in the NHS, but so far it is not being properly developed. Daloni Carlisle explores the challenges debated by the Future of NHS Leadership panel

If you gather some of the most influential leaders in the NHS today and ask them for a robust debate about the future of leadership, that is precisely what you will get.

The leaders who gathered at the Patient Safety Congress in June at Birmingham’s International Convention Centre did not disappoint.

‘To get closer to closing the funding gap, we need a new generation of leadership’

The invitation only event was packed out to hear from three panel members of HSJ’s Future of NHS Leadership inquiry. And not just to listen - they were there to also challenge the panel.

Sir Robert Naylor, chief executive of University College London Hospitals and chair of the inquiry, kicked off with an outline of the inquiry’s findings, which were published in a report in June.

The starting point was the 30th anniversary of the Griffiths report on NHS management which famously concluded that if Florence Nightingale were alive today, she would be searching for the people in charge.

That is no longer true, Sir Robert said. “I was a child of Griffiths. I got my first appointment as a general manager as a result of Griffiths. People today are very much clearer about who is in charge.”

The Future of NHS Leadership inquiry

A leadership revolution

But today’s NHS is “dramatically different” to yesteryear, he said. For example, half the people diagnosed with cancer today will live more than 10 years. Something to be celebrated for sure, but also something that calls for a revolution in leadership.

This brought Sir Robert to his next point about the Griffiths report: the NHS had failed on its very important recommendation to develop clinical leadership.

“In my organisation, one of my leading surgeons can earn more in a morning working in Harley Street as I can reward him in a month as medical director,” he said. “Unless we can find ways of engaging clinical leaders, we have a problem.”

The problem manifests in the shape of a £30bn funding gap. Chancellor George Osborne has pledged £8bn; Lord Carter’s review of productivity has identified another £5bn. But that still leaves £17bn.

“Have you got any ideas about how we are going to close that gap,” he asked dryly. “I certainly don’t. But if we are going to get closer to closing the gap we need a new generation of leadership and we have not got it.”

Given that he was addressing an audience of NHS leaders, this was quite provocative. Could he back it up?

Yes, by referring to the inquiry. It had taken evidence from hundreds, maybe thousands, of people he said, as well as academic literature, and concluded that leadership in the NHS is in crisis.

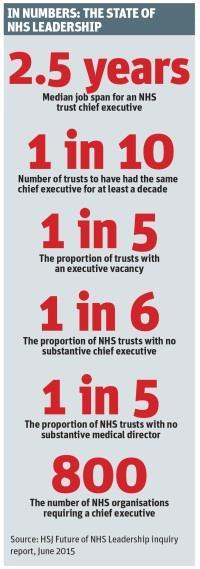

The average job span of a chief executive is two and a half years and only one in 10 trusts has had the same chief executive for a decade or more. One-fifth of trusts have no substantive director of finance and one-sixth have no substantive chief executive. It is the same picture for directors of nursing and medicine. The top people do not want these jobs.

“I have five executive directors in my trust, all capable of being chief executives,” said Sir Robert. “They cannot find a job as there are no jobs that they want to do.”

A new chief executive could not possibly hope to succeed in a failing hospital with a revolving door for top leaders. “Churn is just another way of spelling crisis,” he noted.

Even when inspired managers were in charge, bureaucracy stifles them. Delivering life saving changes to stroke services in London had taken two and a half years and required negotiation with 64 bodies, each with the power of veto, said Sir Robert. Similarly, devo Manc (the nickname for the policy of devolving £6bn health funding to local leaders in Greater Manchester) faces 200 assurance processes.

‘You have to have resilience to be a leader’

He said: “You have to have resilience to be a leader, to be able not to take no for an answer and have the backing from a marvellous organisation.”

The evidence the inquiry heard was remarkably consistent, said Sir Robert, and led inexorably to recommendations based around five broad themes: a call for clinical leadership; a call for empowered leadership; a call for a commitment from our political and professional leaders that leadership is important; a call for less bureaucracy; and a call for an organic reduction in the number of NHS bodies.

On this last point, combining Monitor and the NHS Trust Development Authority was a good start, he said, but nowhere near far enough. No wonder NHS organisations are struggling to find leadership talent - there are around 800 of them each needing a chief executive and chair, he said. No wonder clinical commissioning groups appear to lack power compared to providers. London has 32 groups and his “host” CCG accounts for less than 10 per cent of the FT’s income.

And frankly yes, he suggested, provider organisations needed a cull too in order to concentrate leadership talent. “I would have liked to see [Sir] David Dalton [who reported on the future of acute trusts] be a bit more specific.”

Just in case people in the room had not got the message, he concluded: “We are clearly facing a crisis financially. We are clearly facing a crisis of leadership. The financial black hole will require exceptional leadership to manage the challenge. We must learn to cherish leadership and find ways to capitalise on exceptional talent and dedication in our NHS organisations.”

A systemic look

Stephen Dorrell, who chaired the House of Commons Health Committee from 2010 to 2014 and is a member of the HSJ inquiry, agreed with Sir Robert and went on to address the leadership challenge in commissioning and across systems.

Commissioning has been hit hard by continual institutional churn that has seen talented leaders leave the NHS early and make new posts unattractive to upcoming talent, he suggested. “We have not crystallised leadership thought on the commissioning side,” Mr Dorrell said.

System leadership, he argued, was almost a mythical beast: much discussed but never seen. Politicians will start a speech with the rhetoric around joining up services but then move swiftly on to talk about the NHS.

“The bit they leave unanswered is the leadership that joins the two,” he said. “I do not think devo Manc is a policy - it is a press release. But it gives us a clear direction of travel.”

A third contribution from another inquiry panel member set one more frame of reference for the debate. This time it came from Richard Lewis, partner and health leader at management consultancy EY. In contrast to the rather dark picture painted by Sir Robert, he declared himself optimistic.

He started as a young manager just after the Griffiths report was published. At that time, it felt like a war between managers and medics - a “clash of classes” he called it.

“It doesn’t feel like that to me now,” Mr Lewis said.

His perspective is now from primary care, where he said leaders and innovators are trying to reshape services. The NHS Five Year Forward View’s proposed new models of care will enable them to come out of the wings.

He agreed with Mr Dorrell that system leadership is badly needed. “I am sure devo Manc is a lot of padding and not much substance but it is the right sort of padding,” he said. “There is now a constructive debate with local politicians and it is a debate we see in many parts of the country where people are realising that we survive as a system - or we all fail.”

He had a final proposition about leadership. Where in all this is the voice of the citizen? He said: “The discourse on choice and competition has gone quiet. It poses a question. If you’re taking the power of choice and competition off the table, how do you ensure systems are accountable to citizens? It leaves us only with voice.

“So how then do we make sure systems come together and collaborate so that leadership focuses on the patient voice and that the patient voice does not get lost in the theocracy of ‘we are all in it together’?”

It was a question that the audience would revisit.

The debate

The session was not set up as a Q&A but as a forum for sharing thought, although inevitably the panel did find themselves in the firing line for questions.

Where are the leaders in general practice? What are the qualities needed by leaders to run networks rather than organisations - and are we recruiting to that profile? What are the incentives other than pay that would motivate those doctors with a private practice to forego income in favour of leadership and influence?

Andy Cowper, HSJ’s comment editor, said: “Simon Stevens talks only about provision. We have to get real and acknowledge the fact that care is delivered through providers. If we think it may be cheaper in the long run if we can deliver care in a more integrated way and more in non-acute settings, we need to say how we are going to get there.

“What are the qualities we need in leaders to run networks, and do we in any way shape or form recruit to that set of needs?”

Mr Lewis argued that there is an emerging cadre of GP leaders feeding through as GP practices federate into larger units. “There has been a very big shift in the organisation of collective general practice,” he said. “It is still embryonic.”

‘I do not want doctors to be managers. I want them to be leaders’

On incentives, Mr Dorrell noted that as a former Treasury minister he felt that there was a long history of overestimating the importance of financial incentives.

The argument to win over clinicians needed to be made in terms of delivering better care and placing clinicians as leaders in new accountable care organisations (ACOs), he suggested. “We cannot on the one hand talk about the need for more joined up care services and believe that the answer is to put all of this into UCLH.”

Sir Robert hit back: “I love Simon Stevens. I have known him since he was in short trousers and he is a huge brain. But - and I have said this to him in person - he is responsible for commissioning and not for the NHS. He needs to get down to sorting out commissioning.”

Monitor and the TDA have “completely lost their way”, he added. “I would be amazed if we are less than £2bn overspent on the provider side this year.” In his opinion, providers have lost their voice.

His solution? A strong provider voice needs to emerge from the ashes of the TDA and Monitor; this combined with a strong new chair at the Care Quality Commission would create two powerful bodies that work well together.

Acute trusts need to work towards creating ACOs, Sir Robert agreed. “People like me need to be incentivised to keep people out of hospital,” he said. “The only people capable of delivering ACOs are the leaders of provider organisations. It’s where all the fun is, I love my job, it’s fantastic and I would not want to be a commissioner - and it’s where the money is.”

Maybe if commissioners were more powerful he might change his mind, he joked.

There was a skirmish about whether clinical leadership was really just medical leadership - the panel was clear that they saw all the professions as part of this clinical leadership challenge - but everyone in the room knew that the incentive question really only applied to doctors.

Sir Robert did not answer the question about incentives except to agree it is a “real challenge”. He said: “I employ 850 consultants and 10 per cent of them are in leadership positions. I do not want doctors to be managers. I want them to be leaders.”

He would happily work with GP federations and employ GPs if they wanted him to do so and it would deliver clinical leadership. But they do not, he said.

Sonia Swart, chief executive of Northampton General Hospital Trust and a former doctor, said the issues of incentivising clinical leaders and delivering system leadership were intertwined.

“It is not money that incentivises people, it’s the ability to make a difference,” she said. “It is actually very difficult to work across boundaries because of the lack of system and commissioning leadership. Our doctors are turned off by the fact that it is so difficult to make things happen.”

Charles Ashton, medical director of South Warwickshire FT, said in his experience doctors were interested in building up their own departments. “The more for less and moving things into the community arguments do not turn people on,” he said.

The most dynamic challenge of the afternoon was played out between Jan Ditheridge, chief executive of Shropshire Community Health Trust, and Sir Robert.

The focus on doctors

Ms Ditheridge challenged the assumptions around the primacy of doctors in clinical leadership and acute providers in leading change.

“People who work in mental health and community, and general practice do not rely on lots of medical people but on lots of other types of professionals and the voluntary sector. Until we stop talking about hospitals and medics, we will not really see the shift of power and incentives that we need. I am not convinced that hospitals and medics are the people to lead the big change we are told is needed.”

‘An accountable care organisation breaks down the barriers and it’s no longer them and us’

She continued: “I want hospitals to do what they do well - look after people in crisis - and the community to keep people out of hospital and living the lives they want to lead. I do not think acute hospital leaders see or really understand how to do that.”

She asked Sir Robert: “How do we start to create an environment where we nurture leaders out in the community in health and social care to make sure you do your job properly?”

This was where the ACO came in, he said. “Once you get to an ACO you break down the barriers and it is no longer them and us. We need to engender consensus between organisations. Personally, I think the strength of leadership exists in the big acute hospitals [but] not all them as plenty of big acutes are failing too.”

He talked about developing the next generation of clinical and executive leaders within his trust and again was challenged. “It sounds to me that they will be running organisations like your own,” said Ms Ditheridge. “Can you imagine them going out to manage community or working with local politicians or local services out in the community?”

Sir Robert agreed that there is “fantastic talent across the NHS”. He said: “The key point is that that talent has not been developed in most parts of the NHS.”

Joe Rafferty, chief executive of Mersey Care Trust, picked up Mr Lewis’s point about patient leadership. Nurtured and developed, this could be very powerful, he said.

So where are the new leaders, asked HSJ editor Alastair McLellan. Did Mr Rafferty feel he could lead University College London in the same way he leads a mental health trust?

He was equivocal. Mental healthcare is focused on relationships and operates away from the “white heat” of a busy accident and emergency department, he said.

“We have sat lots of our patient leaders in the same room as our clinical leaders and helped them to understand each other. It is incredible to watch patient leaders challenge medical leaders. I think patient leaders need to be at the leadership table.”

Sir Robert replied: “There is a huge difference between running mental health services and a hospital like mine,” he said. “We treat more than 1 million patient annually from all over the world and finding a patient to take on a leadership role is really difficult.”

Having said that, he had found one of the real benefits of early FT status was the governor role and in many ways these are the patient leaders in acute FTs.

Future leaders would have to learn to work across organisations, said Julie Lowe, chief executive of North Middlesex University Hospital Trust. “Leaders of the future will have to learn to empower,” she said. Others suggested that leaders themselves needed to be empowered by a less controlling centre.

This mention of power was, perhaps, the crunch issue. In a world where even the likes of University College London are projecting a deficit and where money is power, what hope is there for an empowered leadership?

As Sir Robert said in his final comment: “People say to me, ‘we are headed for a £10m deficit already. Why not make it £20m or £30m?’ But we have got to be disciplined or we will all become disempowered.”

14 Readers' comments