Concerns about children’s cancer services in London have – in the words of one informed figure – been an “open secret” for almost a decade, and involved multiple reviews by experts and discussions at the highest levels.

But the public has been kept in the dark and the fundamentals of the service model have gone unchanged.

The service model in south London revolves around the Royal Marsden Foundation Trust effectively “exporting” children who need critical care services in an emergency to other hospital sites from its hospital in Sutton, a London borough bordering Surrey. The south London model, adopted in 2006, also relies on 16 district general hospitals delivering less intensive care for local children. Neurosurgery, another part of the model, is also not provided on site but at St George’s and King’s College hospitals, several miles away.

Guidelines from the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, or NICE, say principal treatment centres like the Royal Marsden should have immediate access to intensive care and neurosurgery.

An investigation by HSJ reveals the Marsden model has been found to be unsatisfactory by multiple reviews and implicated in a series of incidents and child deaths as well as delivering a poor experience for children when they’re at their most vulnerable.

Multiple senior sources have told HSJ of a defensive attitude by the Royal Marsden – at times the trust has refused to engage in reviews or to share data. Several Royal Marsden clinicians told HSJ they shared the concerns about the service but felt they could not speak openly.

One clinician at the trust described shortages of junior doctors, problems with on-site surgical support and children sometimes transferred to St George’s Hospital for routine procedures like the insertion of central lines and venous access for drug infusions.

Speaking anonymously, the source told HSJ: “This has been ongoing for years. Many of us are uncomfortable about it, we know we are outliers and concerns have been raised internally but the message has come down very clearly this is not a problem. The corporate interest is overriding the clinical experience.”

The conflicted interests of Marsden’s chief executive Cally Palmer, who was appointed national cancer director in 2015, have been highlighted in relation to the service. NHSE sets standards for the service as the main commissioner. The cancer specialist FT makes around £20m a year from its children’s services – 10 per cent of its NHS income.

This month a clinical group has criticised NHS England’s national cancer team for, it said, watering down new clinical standards. Draft proposals for the standards seen by HSJ recommended intensive care services be co-located with principal cancer treatment centres – something the Royal Marsden’s Sutton hospital is not delivering and is very unlikely to be able to do.

The Children’s Cancer and Leukaemia Group, a professional association for clinicians treating children with cancer, said it “was very concerned to learn that, after feedback from the national cancer policy team [at NHS England], the requirements for co-dependencies were softened, with no clinical justification, and the word ‘must’ changed to ‘should’”.

It is only the latest development in a pattern of resistance in NHSE to moves to require co-location.

Expert report was ‘buried’

In 2015, a report by Mike Stevens, emeritus professor of paediatric oncology at Bristol University, and nine other child cancer experts, found “the existing fragmentation of paediatric specialist services in London creates a challenge [for wider children’s service changes] on a scale unlike that which may exist elsewhere in the United Kingdom, and which must be addressed”.

It was commissioned following the death in 2011 of Alice Mason which led to a coroner’s warning in 2013 about the safety of the shared care model and fears it could lead to future deaths. Alice’s father Gareth told HSJ his daughter died in “terrible agony” (see his account below).

The report, published for the first time today, called for a single treatment centre in London, with intensive care services on the same site, and a reduction in the number of “shared care” district general hospitals from 16 to nine, with all able to provide at least high dependency care.

Professor Stevens, a professor of paediatric oncology, speaking for the first time about it to HSJ, said his communication with NHS England after submitting his report “was characterised by delay, prevarication and, ultimately, unreasonable criticism as a way of justifying the decision not to publish”.

He said the conclusions “should have been shared openly”. “It was, and remains, a matter of concern to me that Cally Palmer, as the national cancer director, is also the chief executive of the Royal Marsden,” he said. “This creates an obvious conflict of interest.” He said she should step aside from the decision making and there should be an open discussion of the findings.

‘These are still outstanding issues’

The Stevens report was not the first time care quality concerns had been highlighted about the south London network. In 2009 after a series of incidents including two deaths NHS London commissioned a review by the national clinical advisory team – part of the national NHS infrastructure at the time – led by Ian Lewis, a leading paediatrician.

It was completed in 2011 and raised concerns over governance, safety and the experience of patients and families. It said it was “unrealistic to think that it is feasible to continue to provide inpatient specialised cancer services for children on this isolated site”.

Professor Lewis – previously medical director of Alder Hey Children’s FT and currently a non-executive director of an NHS trust – told HSJ he was disappointed the matters he had highlighted so long ago had not been addressed.

“For the good of seriously ill children with cancer these are still outstanding issues and I am at a loss to understand why either the commissioners in London or NHS England have not responded positively to those concerns.”

Asked if he believed there had been a cover-up he said: “The reality is I can’t see any other obvious reason why people would not have acted on the reports.”

In the next attempt to secure reforms, NHS London asked Sir Alan Craft – another paediatrician – to develop child service standards for NHS London in 2013 but the Royal Marsden refused to engage with his work.

Sir Alan told HSJ: “If we are going to have principles about how children should be treated, we should follow those principles and not allow politics to get in the way.”

It is thoroughly unsatisfactory

As concerns about the Stevens report swirled in the system, the Care Quality Commission carried out an inspection in 2016 with a report published in 2017. Inspectors specifically looked at the issue of child transfers.

They found 330 children were transferred either as emergencies or for on-going care to multiple hospitals between 2000 and 2015.

A total of 22 children were transferred 31 times to St George’s Hospital for paediatric intensive care in 2015. Six children experienced at least two transfers between the hospitals, and three children were transferred three times.

The CQC report staff had to use clinic rooms to care for patients who became unwell until a bed became free or the patient could be transferred. While the CQC rated the service as safe it said improvements were needed to ensure the process of transfer was managed effectively. Overall it rated the hospital as “good”.

One source with close knowledge of the inspection told HSJ: “After a lot of thought it was decided it was safe because they essentially export the risk, their patients, to St George’s.

“They have a very low threshold for transferring children. It’s a much higher proportion than you would expect in other children’s units and that was making it safe. But it wasn’t the best experience for the child or the parent. It is thoroughly unsatisfactory.”

Asked why the situation had been allowed to persist, this person said: “Cally is highly protective of the Marsden and highly protected by the upper echelons in NHS England. It’s the only logical explanation.”

‘Why are they so frightened to talk about this?’

A catalogue of avoidable errors by the Marsden and Kingston Hospitals meant two-year-old Alice Mason suffered “terrible agony” before succumbing to irreversible brain damage and dying.

The coroner at her inquest in 2013 described the care failures as “astonishing”. He highlighted more than a dozen problems, including: a breakdown in pathways of care between the hospitals, inadequate communication, a lack of an overall care plan, a lack of monitoring and a failure to listen to Alice’s parents. Alice’s father Gareth told HSJ that the NHS had tried to “push the issues under a carpet”.

He said: “To write a report, shelve it and not debate it. That is a cover up [and] it has left children since Alice in danger, and the Marsden won’t acknowledge that. There is a clear need for a debate. Why are they so frightened to talk about this?”

Alice had originally recovered well after surgery to remove a brain tumour in February 2011. But she was taken ill a month later after becoming dizzy and unable to walk.

Her father said staff at Kingston Hospital “just didn’t know what to do” adding: “Because we were in the shared care system we were being dealt with by people who didn’t have the specialist knowledge.”

He said he tried to get the Marsden to see Alice, but was told to wait until a routine MRI scan a few days later. The scan showed signs of hydrocephalus, or fluid on the brain – but this vital information was not passed to staff back at Kingston Hospital where further scans were not carried out.

By the time her condition became clear it was too late. Her father said: “The pressure was building and Kingston couldn’t do anything about it. She had to go to St George’s and this is where the whole system falls apart. They put her in this situation waiting too long and they then can’t do anything about it. It took hours to transfer her.”

Further delays meant Alice wasn’t operated on until 6pm, eight hours after being first identified as needing urgent surgery. She survived the operation but suffered irreparable brain damage and never regained consciousness. She died on 31 March. Her inquest was told had she been operated on earlier there would have been less brain damage or even none. Alice’s parents believe that her death was directly attributable to the delay at Kingston and the further delay at St George’s Hospital.

Her father Gareth said the existing shared care system was a “lottery” adding: “We can’t run this on a lottery where we accept a few casualties. If the Marsden can’t follow the NICE guidelines there is always a danger this could occur.”

‘There is the potential for this to blow up in our faces’

Once the Stevens report was passed to NHS England it was repeatedly omitted from formal discussions at its specialised services committee, well-placed sources said. Months passed with no progress.

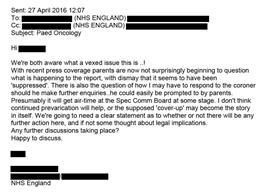

In an email between two NHS England officials [names redacted] in April 2016, one said: “Parents are now not surprisingly beginning to question what is happening to the report, with dismay that it seems to have been ‘suppressed’.

“I don’t think continued prevarication will help, or the supposed ‘cover up’ may become the story in itself. We’re going to need a clear statement as to whether or not there will be any further action here, if not some thought about legal implications.”

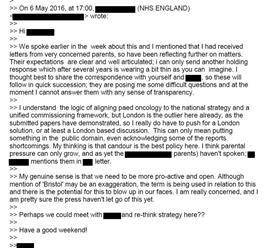

A few weeks later another email revealed parents were asking questions, with an official stating: “I can only send another holding response which after several years is wearing a bit thin as you can imagine… they are posing me some difficult questions and at the moment I cannot answer them with any sense of transparency.

“Although mention of ‘Bristol’ may be an exaggeration, the term is being used in relation to this and there is the potential for this to blow up in our faces.”

At the same time, Professor Stevens wrote to NHS England pleading for action: “I must again point out that it is now 15 months since I submitted the report from the review panel and have yet to be provided with any justification why a decision about its publication has not been reached.”

In May, former NHS England director of specialised commissioning Jonathan Fielden wrote to him saying himself, Sir Bruce Keogh and the national clinical director Chris Harrison had discussed the report. He said the proposals would have “significant capital and revenue implications” and the report on its own “would not give the full picture” and could concern patients and staff. He said the issues would instead be considered as part of a national cancer taskforce – a process at that point being put in place to review cancer policy nationally.

Andy Mitchell, then NHS England’s medical director for London – who had pursued the issue – wrote to Dr Fielden to express his frustration with the plan to include the issues in the national taskforce work.

He said: “I do not think it will have credibility with the profession, nor do I think it would stand up to public scrutiny… I feel obliged to state my disagreement.”

He noted the previous reviews - “upon none of which has the system taken any significant action” – and pointedly referred to conflicts of interest on the issue which he said needed to be acknowledged.

‘His suffering was completely avoidable’

Eight-year-old Daniel Strong suffered unnecessary agony in the final weeks of his life because of the “disorganisation” of South London’s cancer services and the Royal Marsden’s reluctance to take control of his care, according to his parents.

Daniel was transferred multiple times between Epsom Hospital, the Royal Marsden’s Sutton site and St George’s Hospital before he died in February 2009 at St George’s, seven months after being diagnosed with an aggressive form of leukaemia.

His mother Jo described the transfers as “horrifying” and Daniel as being “petrified” throughout. His relapsed leukaemia was not recognised for 10 days by staff at Epsom Hospital who tried to raise concerns with the Royal Marsden on three occasions, the parents say.

Father Mark also asked the Marsden to see his son, but they declined. Daniel’s parents described those 10 days as an “utter nightmare” with staff at Epsom “out of their depth”.

“If the Marsden had taken one look at him, they would have seen immediately that it was a relapse,” said Mark.

Jo continued: “When we got to St George’s, he was put straight on IV pain relief and we just saw this little boy uncurl, it was one of the worst moments. His suffering was completely avoidable.”

Mark added: “I feel NHS England deliberately suppressed the reports. The Marsden feel they are beyond criticism, while NHS England are actively obstructing any criticism. The way the service is set up is contributing to an increased risk. NHS England have been told that repeatedly.

“What does it say about the NHS if they are willing to sweep all that under the carpet?”

The Stevens Report

The final version of the report by Professor Stevens and his panel was delivered in 2015.

They were asked to consider the right number of treatment centres for London, what critical services they should have and the model of “shared care” for smaller hospitals.

The report concluded:

- There should be a single treatment centre with services including critical care co-located.

- The existing model required good governance, excellent communication and experienced clinical teams on all sites. It noted “serious clinical events have occurred in London which relate to failures in these areas”.

- It said previous recommendations from earlier reviews had not been acted on, adding: “there is evidence of continuing concern amongst families of children… about fragmentation of service delivery, poor communication and lack of access to skilled and knowledgeable staff at all points in their child’s treatment pathway.”

- The report said clinicians were concerned about poor communication, governance and too many POSCUs delivering low complexity care.

- It said the number of POSCUs should be reduced to no more than nine with all capable of delivering intensive care.

- The panel said the failure to act on previous warnings raised “a serious concern about commitment to change structures in order to address patient safety issues”.

- It said: “The existing fragmentation of paediatric specialist services in London creates a challenge… on a scale unlike that which may exist elsewhere in the United Kingdom, and which must be addressed.”

- A total of 18 out of 21 organisations, 86 per cent, told the panel existing governance arrangements between POSCUs and the PTCs were not adequate.

- A survey of clinicians resulted in more than two thirds saying services should be on one site, with 94 per cent saying there should be fewer shared care units.

Among the comments made to the panel by clinicians, one said the different systems and governance at separate units increased the “margin of error” while another said that while governance had improved “there are still inadequacies particularly around the urgent care of sick children not yet requiring intensive care or children with unpredictable need”.

Parents and children who had experienced care expressed “dissatisfaction with the current POSCUs and that more expertise (training and skills) is required on site, including basic skills, communication between the PTC and the POSCUs and a named accountable person for their child’s care”.

The NCAT report

Professor Ian Lewis’ review was finalised in 2011 and found major issues with governance between the Royal Marsden and St George’s Hospital.

It said: “The current service at RMH does not meet the standards for children’s high dependency care expected of any centre that admits children for inpatient care.”

It added: “The model far from being a two-centre model actually uses four centres… The governance structure of the joint PTC is weak… there appears to be a lack of recognition by the boards of their shared responsibility for this service. As an example of this it was made clear to us by the RMH executive team that they thought they had no responsibility for the SUI at SGH that precipitated this review.”

It recommended co-locating services on one site, saying: “It is unrealistic to think that it is feasible to continue to provide inpatient specialised cancer services for children on this isolated site.”

When the NCAT report was published in 2011, Ms Palmer wrote to NHS London querying a lack of evidence, adding: “Recent serious untoward incidents are unrelated to the PTC model”. She said there was “an external agenda of consolidation which was apparent from day one of the review”.

In its own response, St George’s Hospital recognised internal issues but also added: “There have been occasions when the full support of all parties involved was not felt to be as strong as it could have been.” It added: “We support the recommendation of a single site model for the sickest children in the long term and feel this would provide the safest and most consistent care for children.”

Almost 10 years on, the model remains split between the two sites.

An ‘open secret’

The concerns about the Marsden and the alleged cover-up of the issue has been discussed among professionals for several years.

One senior clinician with knowledge of London cancer services said the issues had been an “open secret” for years, adding: “This has been a problem in the system for both adults and children for a long time. The Marsden is viewed by many people as being untouchable as they have a lot of influential friends.”

One separate former NHS England director told HSJ there was a wrangling over the findings of the different reports “because people did not want to stomach the political implications of having a fight with the Marsden and when your national cancer director is the CEO of the Marsden it is very difficult”.

“NHS England corporately covered up [the Stevens report] – that would be my personal view.”

A senior figure from NHS England London team confirmed to HSJ that there had even been discussions brokered between the Royal Marsden and the Evelina Children’s Hospital, based at St Thomas’s hospital, about a possible “Marsden at…” model of care, which could have co-located services. This was supported by some clinicians but was blocked by the Marsden board, HSJ was told.

The Marsden has pointed out that overall mortality figures for the network are not poor.

However, a senior policymaker said: “What matters is the outcomes and outcomes are more than life and death but also the quality of care children get during treatment for one of the most serious and life-threatening illnesses you can have.

“It is extraordinary that people don’t take into account the totality and simply concentrate on outcome figures in defence of what is acknowledged in the children’s world not to be best practice.

“If NHSE can suppress reports and issues like this how can we be certain it hasn’t done this with other areas?”

Downloads

NCAT South London Paediatric Oncology Review - Report

PDF, Size 0.28 mbLondon Paediatric Oncology Review Panel Report 2015

PDF, Size 2.03 mb

Exclusive: NHS England ‘buried’ concerns over child cancer services

NHS England covered up serious problems with paediatric cancer care in London – which had seen children dying in “terrible agony” – and has “buried” attempts to overhaul the services, an HSJ investigation has established.

- 1

- 2

Currently

reading

Currently

reading

Investigation: The cancer service failings covered up for years

No comments yet