Average waiting time targets will make the numbers look smaller, but that’s about it. Field testing should explore other options that might actually deliver the review’s aims. By Rob Findlay

The Clinically-led Review of NHS Access Standards has recommended testing average waiting times as an alternative to the current “92 per cent within 18 weeks” elective target.

Testing policies before implementing them is an excellent idea that should be adopted more widely. But this particular proposal is pointless, and instead the testing phase should explore a wider range of options that might actually deliver on the review’s worthwhile aims.

Halving the numbers

To see why average waits are pointless, imagine an ordinary British queue like the one at the Post Office. There are four people in the queue, somebody is served every minute, and a new person joins the queue every minute. So everybody in this particular queue waits four minutes to be served.

If we take a snapshot of this queue, we might find that the four people have so far been waiting:

- 0.5 minutes (the person at the back who has recently joined)

- 1.5 minutes (the person in front of them)

- 2.5 minutes (the person in front of that)

- 3.5 minutes (the person at the front who will be served next).

So the average waiting time of the queue is two minutes, which is only half the four minutes that everyone waits before they are served. So the average waiting time of the queue is not representative of the customer experience.

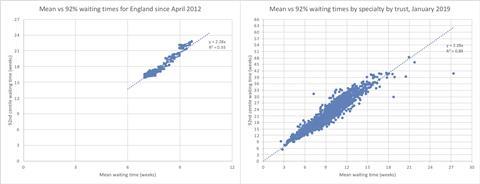

After that insight, the charts below will come as no surprise. They compare the current “92 per cent” target against the proposed (mean) average target, firstly for the total English waiting list every month for the last several years, and secondly by specialty by trust in the most recent snapshot.

Guess what? The average wait is about half the “92 per cent” wait! And that is why this proposed change is pointless, because all it does is roughly halve the reported numbers.

Eight weeks is the new 18 weeks

In fact the correlation is so strong that we can use it to translate between the current target and the new one. So when the review says “To be clear: we are not proposing that new standards should require non-urgent patients to wait longer than they do now”, we will know the promise is being kept if the new target is set no higher than an eight week average wait.

Actually I would argue that average waits are a bit worse than pointless, because they are a poorer representation of the waiting times experienced by routine elective patients requiring treatment. While many patients get a “clock stop” much more quickly than 18 weeks, mostly because they are clinically urgent or discharged early in the clinical pathway, a major reason for having waiting time targets is to reassure all patients that their waits will not be excessive.

Or to put it another way, patients don’t care how long everyone else in the queue has been waiting (which is what the proposed average would measure). They care how long they are going to wait, and that is what the current target addresses.

Missed opportunities

These proposals could have been so much better.

Firstly, the review rightly frets that the current target focuses on a particular point in time (18 weeks) and should pay more attention to those patients who are waiting longer. This one is easy. Instead of tracking the percentage within 18 weeks, just track the number of weeks within which 92 per cent of the patients are waiting – this measure is already in the official statistics and would not require any change to the target.

Secondly, the clinical review expressed concern that the huge changes to outpatient services envisaged in the NHS long-term plan will mess up the current measures. They are right, but average waits do nothing to address this problem. Instead the current referral-to-treatment target should be split into two stages:

- from referral up to the decision to be treated (which bundles up the relatively cheap but complicated bits of the pathway that will be disrupted by outpatient transformation); and

- from that decision up to treatment (the expensive but simple bit of the pathway that will not be disrupted, and where the longest waits lie).

If those two stages add up to 18 weeks or less, then the public can have confidence that no sneaky relaxations of the target are going on. And if the first stage is reasonably short, the change will promote safety by ensuring that patients see a specialist without undue delay.

Safe care for urgent patients

Thirdly, the review has not addressed its aims of “further improving and speeding up care for the most urgent conditions” in elective care, and here the next step should be the introduction of supporting measures rather than targets.

Hospitals already record each patient’s clinical urgency, and NHS England should start using this data to monitor whether urgent patients are being seen and treated as quickly as they should be. Hospitals also usually record whether follow-up outpatients are overdue, and this should be monitored as well.

As I said at the start, it is welcome that these proposals are being tested before taking their final form. But instead of testing only one (rather neutral) idea, why not test a variety that could actually make a difference?

Dr Rob Findlay is director of software company Gooroo Ltd,

7 Readers' comments