Ben Richardson and Sutha Satkunarajah note that a review of the healthcare system in England has found that though certain quality outcomes have improved over the last 10 years, timely access to services has become tougher

The NHS’s 70th birthday is a prime opportunity for a health check. Over the last 10 years, the nation’s health and social care services have seen improving quality outcomes in some important areas, but increasingly, people are struggling to access these services in a timely manner.

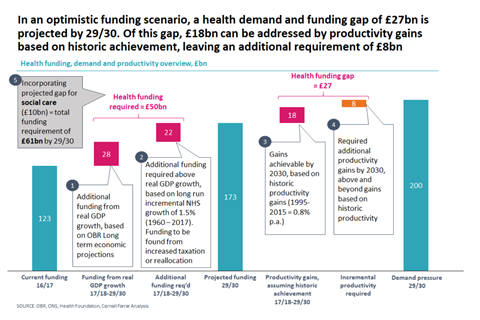

Additionally, the NHS faces severe financial challenges - by 2029-30 there will be a £27bn gap between health demand and funding per year. To bridge this gap, productivity within the system must improve by one and a half times the levels of historic achievement.

These findings come as part of our work with IPPR and Professor Lord Ara Darzi, as part of a review of the health and care system in England. We have conducted analysis to assess population health, quality and access over the last 10 years, as well as examined future funding scenarios for the NHS.

Population health: people are living longer, though not better

While UK life expectancy has continued to rise since 2008, the rate of growth has slowed, and there is significant and growing variation within the UK – both regionally (life expectancy in the South is around 2.5 years higher than in the North) and between socio-economic classes (“Higher Management and Professionals” are expected to live 4-6 years longer than those within the “Routine” class).

Since 2008, alcohol and smoking consumption rates have declined, each falling by 2 per cent a year. The proportion of adults who are overweight or obese has plateaued at over 60 per cent of the population; however, obesity rates of children aged 10 have risen by 5 per cent per year for the past decade.

Quality: outcomes for patients have been improving

The quality of healthcare services (defined as patient safety, experience and effectiveness of care) has improved in some important areas over the last 10 years. In particular, significant progress has been achieved in secondary care, while primary care, social care, and mental healthcare have also seen modest improvements.

Most notable progress has been made in secondary care – outcomes have improved across the board, with cardiology, stroke, cancer, and maternity care all seeing improvements. Cardiac surgery mortality rates have dropped by 1 per cent overall and 2.5 per cent for complex procedures since 2006, against a backdrop of an increasingly complex surgery case-mix. Stroke 30-day mortality rates have decreased from 21 per cent in 2008 to 16 per cent in 2015.

Most notable progress has been made in secondary care – outcomes have improved across the board. Measures of quality outcomes in primary care have seen modest improvements

Cancer survival rates have steadily improved, with the one year survival rate rising from 67 per cent in 2008 to 72 per cent over the same period (it should be noted, however, that compared to other countries, the UK underperforms in five year survival for most cancers). Maternity care has improved, with a fall in both maternal and infant mortality rates by 5 per cent and 2 per cent per year. Patient safety has also improved, as the proportion of patients receiving harm-free care has increased from 92 per cent in 2012 to 94 per cent in 2017.

Measures of quality outcomes in primary care have seen modest improvements, and measures such as the levels of childhood vaccinations have also risen encouragingly. Social care has also seen some improvements in quality, with the proportion of social care users who feel they have control over their daily life increasing from 75 per cent to 78 per cent between 2010-11 and 2016-17. Mental healthcare has also seen improvements, for example, there has been an increase in the number of patients with anxiety disorders and depression referred to talking therapies, increasing by 57 per cent since 2012-13.

Timely access to services is becoming more difficult

The gains in quality outcomes have been delivered against a backdrop of declining access. Rising problems with access have been seen in social care, primary care, and acute care, with particular issues being faced within urgent and emergency care. This has contributed to a fall in public satisfaction.

The number of those accessing publically funded social care fell by 5 per cent per year between 2008-09 and 2016-17, despite the number of requests from new clients to receive social care support staying at 1.3 million in 2014-15, 2015-16 and 2016-17. Additionally, the level of unmet need within social care is high – amongst the lowest income groups, of the 35 per cent of over 65 year olds who need help with activities of daily living, only 12 per cent received the required support.

Since 2008, the proportion of patients waiting in accident and emergency for more than four hours increased by more than five times

Access to urgent and emergency services has reached crisis point. Since 2008, the proportion of patients waiting in accident and emergency for more than four hours (before being seen, treated, and admitted or discharged) increased by more than five times. At the same time, the number of “trolley waits” (time between decision to admit and admission) greater than four hours increased by more than eight times, rising from 73,000 in 2008-09 to 614,000 in 2017-18.

Satisfaction in services appears to be declining as a result. Patient satisfaction with GP services has fallen, with the proportion of patients rating their overall experience as “very good” or “fairly good” decreasing from 88.4 per cent in 2012 to 84.7 per cent in 2017. Equally, public satisfaction in the NHS has fallen in the last few years, with the proportion of the public dissatisfied with services almost doubling, from 15 per cent to 29 per cent between 2014 and 2017.

Funding challenges: a need to plan for 2030

The increasing cost of health services has a number of drivers: demographic, non-demographic and provider cost inflation. With regards to demographic changes, the gains in life expectancy and the improvements in health outcomes have led to an increasing median age within the population. ONS analysis indicates that by 2030, the population over 65 will increase by 30 per cent.

Due to the high prevalence of long term conditions amongst the elderly; this places a significant cost burden on the NHS. Combining this with non-demographic drivers, including technology, and provider cost inflation (such as wages, and cost of drugs), results in a projected health demand pressure of £200bn in 2029-30.

Meeting this level of health demand is a significant challenge. Our analysis projects that unless funding increases substantially than previous levels, funding for the NHS in England is set to grow from the current £123bn to £173bn, by 2029-30 in real terms (this assumes a continuation of the average growth rate between 1960 to 2017, which equates to real GDP + 1.5 per cent).

There will be a projected gap between health demand and funding of £27bn by 2029-30

This implies an extra £50bn funding must be found for health funding by 2030 (£28bn of which is projected to be driven by real GDP growth – leaving the remainder to be found from increased taxation or reallocation).

This results in a projected gap between health demand and funding of £27bn (£200bn – £173bn) by 2029-30. The reality of how this gap would be bridged rests with policy makers – both current and future; however, if left to productivity alone, the levels of productivity gain required would be one-and-a-half times the historic levels of achievement.

With regards to social care, The Health Foundation projects that there will be approximately a £10bn gap between the level of provided funding and the required spend. Taken together with the additional £50bn required to fund healthcare in 2029-30, this produces a minimum combined funding requirement for health and social care of £61bn, per year, by 2029-30.

1 Readers' comment