Do mobile NHS staff have to travel by car or is it practical for them to take alternative methods such as bikes, electric cars and car shares? Steve Melia set out to find the answer

The NHS is responsible for around 5 per cent of all the traffic on Britain’s roads. Its carbon management plan commits the NHS to a 10 per cent reduction by 2015.

Transport accounts for nearly a fifth of its carbon emissions, of which a quarter is due to work travel. Those trusts which have travel plans often overlook work travel – concentrating entirely on visitors and commuting.

A study in Bristol aimed to explore whether it is possible for mobile staff – particularly in community-based teams – to reduce their use of private cars.

‘For staff, the “de-stressing” properties of cycling, particularly on the off-road paths were contrasted with the stress of driving in heavy traffic’

In 2009, Avon and Wiltshire Mental Health Partnership Trust introduced a pioneering scheme which offered electric bicycles and one electric pool car as an alternative to employees’ own cars or bikes, initially for one team, which became known as the “zero petrol team”.

The scheme was later expanded, with the purchase of 20 diesel Smart cars for use by staff across the trust’s sites in Bristol. In 2012, the Go Low project was set up as a separate social enterprise which continues to provide similar services to the trust, and other employers. This study used the trust as a case study to explore the travel patterns and needs of mobile NHS professionals.

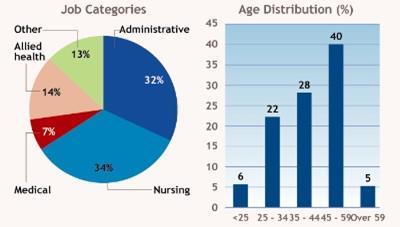

The study used an online survey, telephone interviews and a focus group. The survey was completed by 306 staff based in the Bristol area.

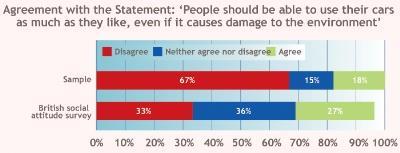

The survey included measures of attitudes towards transport and the environment, including the one shown in Figure 5, which suggests that Avon and Wiltshire Mental Health staff are more “pro-environmental” than the general population.

Reasons for driving

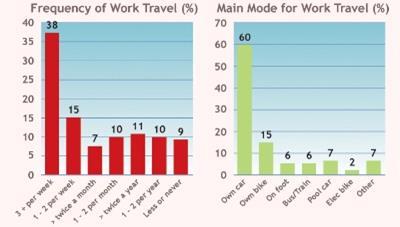

Some interviewees referred to the unpredictability of their travel needs. This was particularly the case for members of the crisis teams, who could be called at short notice to home visits anywhere within their (city or district-wide) area. The most cited reason for driving for work, by 37 per cent, was the need to travel straight from home to an external site. Several interviewees mentioned this was their normal pattern.

Carrying equipment and dropping off other people were mentioned as reasons for driving by 18 per cent and 16 per cent of the drivers in the survey. Most of the interviewees mentioned occasionally carrying other people, usually clients, as passengers.

The availability of pool cars was important to those who did not have a car available for commuting. It also changed the commuting patterns of many others: 30 per cent of pool-car users had reportedly reduced their commuting by car as a result. This had brought particular benefits for those inner-city sites where parking is limited.

Eleven per cent of women and 23 per cent of men reported cycling as their main mode. Bristol’s status as a cycling city was mentioned several times in the focus group.

One community nurse interviewed neither drove nor cycled. She used a combination of walking and buses, including two bus journeys in some cases. She would occasionally take a taxi and colleagues would sometimes offer lifts if they were driving in the same direction. “I would not ask for a lift unless I was desperate,” she explained.

Operational problems

In its recruitment policies, Avon and Wiltshire avoids discriminating against people who do not drive. Team managers explained that they could accommodate a minority of staff who neither drove nor cycled – although a larger proportion would create operational problems.

The pros and cons of giving lifts to clients were discussed in the focus group with the zero petrol team. The switch to (mainly) electric bikes had reduced their propensity to offer lifts to clients.

‘There was unanimity that the electric bikes were quicker and more reliable than driving’

One participant expressed a view on this, which appeared to reflect a consensus: “In some ways that is good for the client because you are saying to somebody ‘you have to get there’ rather than just automatically say ‘I will give you a lift’. You are making them a bit more independent.”

There was unanimity that the electric bikes were quicker and more reliable than driving. Two participants said clients were more appreciative of, or responded better to, staff who travelled by bike.

Increasing motivation

For staff, the “de-stressing” properties of cycling, particularly on the off-road paths (of which Bristol has several) were contrasted with the stress of driving in heavy traffic. The link between the states of mind of staff and clients was believed to be particularly important in a unit involved in support and recovery.

Some participants including the team manager believed the scheme had reduced sickness absence, although it was not possible to obtain any quantitative data on this. There was a consensus that the electric bikes had brought the team together in other ways – increasing their motivation and their socialising outside of work.

A team culture of cycling had reduced the gender difference found elsewhere in the organisation. Several of the female staff had taken up cycling, or utility cycling, for the first time as a result of the change. The way in which new members are inducted into the group is important to this process.

This study suggests that much work travel by mobile NHS professionals in a relatively compact urban area such as Greater Bristol can be done by means other than the private car.

Travel culture

Many of the staff who mostly travelled by other means reported occasional needs for a car – hence the importance of pool cars. These are considerably more fuel efficient and lower in emissions than employees’ own cars. At Avon and Wiltshire Partnership, their cost was comparable to the alternative of paying mileage rates, but the real potential for savings comes from employees switching to walking, or cycling in particular.

‘Leadership from local management is a vital factor in fostering a change of travel culture’

Work travel also impacts on employee’ commuting behaviour. Changing patterns of work travel can also bring benefits to clients – particularly where mobile professionals are involved in motivating clients to change their own behaviour.

Trusts concerned about carbon reduction and parking problems should ensure their policies – particularly in recruitment – encourage and do not present barriers to mobile staff who want to travel by more sustainable means. Leadership from local management is a vital factor in fostering a change of travel culture.

Dr Steve Melia is a senior lecturer, centre for transport and society, department of planning and architecture, University of the West of England.

Downloads

Survey results

WordMarie Curie graph

PowerPointMarie Curie graph 1

PowerPoint

No comments yet