The idea of collective management of finite resources and adopting a culture of stewardship can lead to sustainable governance. Explain Dr Tim Wilson, Nick Relph and Dr Joe McManners.

Most of us are familiar with the role of health economists in cost-effectiveness and value for money assessments. Some of us are keen to put in place the work of Nobel prize winning economist Richard Thaler: nudge theory.

But the work of Elinor Ostrom, the first female Nobel prize winner for economics in 2009, is perhaps the most pertinent to those running integrated care systems, in which the espoused goal is the “collective management of resources for the delivery of NHS Standards and improving the health of the population they serve”.

Indeed, her work is applicable to any situation where sustainability is threatened by “excessive” demand upon finite resources. Therefore, Ms Ostrom’s thinking is just as pertinent to integrated care providers in England, health boards in Scotland and Wales and health and social care trusts in Northern Ireland.

Drivers of demand

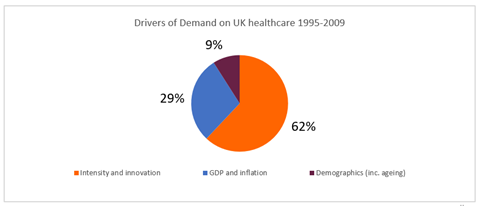

First, we need to understand the causes of “excessive” demand that threaten the sustainability of health services. The Office for Budget Responsibility outlined in their report on health spending in the UK that the principal demand is not, as is sometimes stated, demographic change (eg ageing), but instead trends driven by clinical practice (see figure below), including the increase in the volume and intensity of testing, prescribing, surgery and other interventions.

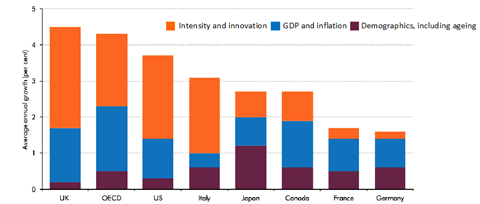

The UK is ahead of other OECD countries in this regard (see figure below)

The point being, it is not the planned request for greater budgets that threatens the sustainability of health services, but increasing the volume and intensity of clinical practice that requires CEOs and CFOs to ask for higher budgets. This goes a long way to explain why planned levels of activity rarely match actual end of year outturn. Memorably, David Eddy, described how clinicians simply do more and more, using the phrase:

“The relentless increase in the volume and intensity of clinical practice”.

The drive to increase the intensity and volume of clinical practice is generated every single day in the millions of consultations in the NHS, and the tens of millions of decisions made by individuals as to whether to self-care or seek care. The complexity of these interactions means that this is not something that commissioners or provider boards are easily able to address.

More is not always better

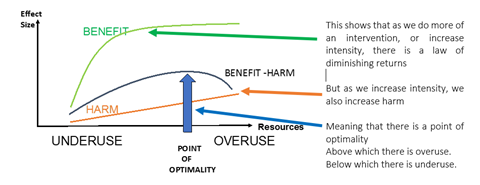

The increasing volume and intensity would be reasonable if it were all of high value. After all many treatments are modern miracles; cancer treatment, hip replacements, MRI scans, statins. But as Donabedian has taught us, more is not always better (see figure below).

Because of the fragmentation in the way health and care services are organised, not so much structurally, but more importantly professionally and culturally, we are not able to understand or achieve, the optimal use of resources. Indeed, professional biases mean that priority setting based on need and sustainability is rarely achieved.

Stewardship of finite resources

Ms Ostrom, the first woman to win the Nobel prize in economics, found in her careful observational research that local communities, given finite resources, were able to use those resources sustainably for the good of their local community. She observed that local groups of users developed sophisticated ways in which they took collective responsibility for the management of resources. She found a culture of stewardship that sustainably and wisely used finite resources.

She distilled her findings into a set of principles which we can use in the NHS. For ICSs, or integrated care partnerships within them, to take “collective responsibility for the management of resources” and have the chance of sustainably managing demand, there are four key tasks:

Task One: Work in populations. In this task an ICS is both defining population groups and determining the resources to be used in improving the health of that group. Berwick describes the creation of geographically based population pools as the creation of ‘regional health commons’.

However, purely defining population by geography creates too much heterogeneity. So, another level of segmentation is required within each geography, segmentation by need. Any population segmentation process is subject to compromises, but one that seems most promising as it recognises the complexities of co-morbidities, end of life and frailty, and of disease specific issues, is Bridges to Health.

Indeed, NHS England is piloting its use and considering its roll out. The biggest risk we face is that different parts of the NHS choose different segmentation approaches, meaning that learning and benchmarking becomes impossible, except using ICD disease groups.

Although resources allocated to these population segments will be defined by historical patterns of expenditure, in time, the quantum of resources should move from historical allocation to needs-based allocation.

Task Two: Create a common purpose. For each of these population segments, we need to first determine and then improve the outcomes that matter to them. These will be a mix of measures of individual outcomes and overall population level outcomes, like social participation.

Finally, there are objectives common to all population segments, echoing the founding principles of the NHS, including reducing inequity, deploying resources based on clinical need, delivering value for taxpayers and being accountable (eg through the publication of an annual report).

Task Three: Organise to govern common resources. Key to Ms Ostrom’s work was her observation that the sustainable stewardship of resources was determined at a local level, not by external agencies. A local culture of stewardship emerged.

This implies that ICSs/ ICPs need to devolve the authority and responsibility for resource use to place or neighbourhood level. Given the need to work in population segments, no single team, department or organisation would adequately represent the users of the resource; therefore, ICSs and ICPs will need to create networks at a place or neighbourhood level, drawing from all appropriate stakeholders. Crucially, these networks need to include patients, public, and patient representative groups as well as clinicians.

Task Four: Create a culture of stewardship. ICS and ICP leaders will need to create a new culture of stewardship amongst networks. This includes establishing and using a new common language, establishing and reinforcing positive behaviours that promote stewardship and creating artefacts, like an annual report, that represent a tangible demonstration of a new culture.

Conclusion

Until we create the conditions for the local governance of common resources, including learning, development and accountability, the NHS will continue to grow unsustainably, with high levels of waste and low-value care.

But there is much to be learnt from the work of Ms Ostrom, especially since her work so comprehensively described how collective management of finite resources can be done sustainably. We believe that by adopting a culture of stewardship we can sustainably govern the NHS, now and for future generations.

1 Readers' comment