Years of critical reviews have failed to bring about the required changes in child and adolescent mental healthcare services. Establishing a good case for improvement is important to move beyond just analysing the problems, argues Karen Smith

child and adolescent mental health services

The Health select committee report on child and adolescent mental health services (CAMHS) published in November last year made headlines, with officials warning of “serious and deeply ingrained problems”.

‘Why does there appear to be stagnation and a lack of response to the pressures for change?’

Issues were cited from across the spectrum of services, from care for those in need of an early intervention to those in need of specialist care. It comes at a time of almost weekly reports in the national press about young people being placed in police cells or on adult wards due to lack of beds within specialist facilities.

Through our experience of working in mental health and with CAMHS, we recognise the deep rooted problems, but suggest that the challenges are very familiar. There has long been recognition (including within other national reports) that CAMHS, in many areas, are contending with serious issues.

- Revealed: Mental health pledge to be funded from existing budgets

- Rhetoric is not enough: Prove parity of esteem with action

- Sign up to receive the weekly mental health newsletter

What needs to be done?

Why, if the distress of CAMHS is widely known and accepted, does “news” that services need a major overhaul seem to hit the headlines so regularly?

So why does there appear to be stagnation and a lack of response to the pressures for change?

‘There is an apparent inability to move beyond analysis of the problem’

What needs to be done to break the apparent paralysis that characterises CAMHS?

In the last 20 years, we have had three other significant reviews of CAMHS. Each of them, with their saddening findings, seemed to herald a new age.

These include:

- the health advisory service thematic review Together We Stand (1995);

- the Audit Commission report Children in Mind (1999); and

- the national CAMHS review (2008).

All looked at CAMHS from a slightly different perspective, but all referred to a common set of issues, particularly the need for:

- stronger leadership;

- service mapping;

- higher quality early intervention services (tier 1) and specialised services (tier 4);

- clear roles and responsibilities (across and within teams);

- better training; and

- clearer pathways and seamless services.

Move further

In each case, while the report findings were accepted, they have not kick started the change anticipated. There is an apparent inability to move beyond analysis of the problem, despite stark warnings of the risks presented. Why is this and what are the prospects for change in the immediate future?

To assess the climate, we have analysed a sample of clinical commissioning group five year plans to measure the extent to which CAMHS features. We also looked at:

- where it sits within priorities (if at all);

- the potential financial investment that might be awarded to it; and

- the clarity of any objectives presented.

‘There’s an inability to move beyond analysis of the problem, despite stark warnings of the risks’

A high level content analysis of plans is an opportune and cost effective means of gauging where CAMHS is positioned within the psyche of commissioners (although we acknowledge the role of NHS England in commissioning CAMHS too).

Our methodology focused on appraising a random sample of 70 CCG strategies through a web based search. Of the 70 sample CCGs, only 56 made their strategies publically available on their websites, reducing the sampling frame from 33 per cent of all 211 CCGs in England, to 26 per cent.

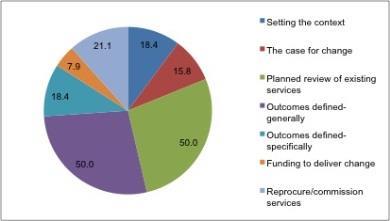

Our analysis showed that 68 per cent of these strategies mentioned CAMHS directly, and enabled us to group these CAMHS references under the themes illustrated in the chart below.

The chart shows that:

- In 18.4 per cent of plans the context for CAMHS was set out - for example, by describing who provides local services. Two CCGs did this, but then made no further reference to CAMHS.

- 15.8 per cent included some text presenting a case for change - for example, the lack of specialist beds, an increase in CAMHS referrals and historic underinvestment.

- 50 per cent of plans committed to reviews of CAMHS. Six plans made this commitment, but no further details were given, such as what prompted a review or the outcomes expected.

- In respect of outcomes, 50 per cent of plans defined the outcomes they hoped to achieve for CAMHS generally - for instance, “improve CAMHS”; 18.4 per cent were more specific, writing of their ambition to prevent the escalation of needs to tier 3, to extend services 24/7 or to ensure inpatient bed provision meets local needs.

- Only 7.9 per cent suggested that funding might be available to support change, though more than 20 per cent planned to recommission services.

A key observation was that a significant number of CCGs plan to review and recommission or reprocure services.

However, the purpose of this, if described at all, is only presented in very general terms - for instance, “to sustain services”, “to continue to develop CAMHS” or “to deliver integrated CAMHS”.

‘There is always a louder voice competing for attention’

The most salient result, however, is the lack of a coherent and complete CAMHS story in the majority of documents. Only one or two cases were found that comprehensively described the:

- local context and case for change;

- outcomes that investment must achieve;

- funding for the work; and

- recommissioning activity that would follow.

While the lack of a comprehensive narrative may be indicative of gaps in strategic thinking, it is positive that CAMHS is included in so many plans. However, this exercise suggests further work is needed before CCGs are prepared and able to create the seismic transformation needed.

With a multitude of competing priorities banging on the door, this is a concern for those with a heart for CAMHS.

Perhaps this is the crux of the CAMHS problem: there is always a greater population cohort, with more costly needs and a louder voice competing for attention.

Leadership is critical

Despite this, we believe that change can be achieved within CAMHS. Creating the right leadership is critical.

Leaders must have the authority, charisma and weight to make decisions (sometimes unpopular) and engage, in a genuine and sincere way, all stakeholders.

Secondly, prior to any decisions about what is needed, a comprehensive case for change must be built, based on good information. This is likely to be a difficult task (particularly if information systems are not the most sophisticated) but is fundamental for proceeding.

‘CAMHS service planning must be based on reality rather than anecdotal evidence’

Without it, it will not be possible to explain and justify to the wider world why this matters. There are many myths around CAMHS and service planning must be based on reality rather than anecdotal and supposed evidence.

A good case for change will articulate the current level of demand and the nature of that demand. It will allow leaders and stakeholders to debate whether services are meeting the right needs, how those needs are being met and the level of unmet need that remains to be met.

By prioritising these two steps, the issues expounded in the Health select committee report and those that went before it can start to be tackled. They are undeniably very serious problems, but by taking one step at a time and “getting real” about the challenges confronting CAMHS, we can build services that provide the right support for our children and young people.

Karen Smith is a senior consultant for GE Healthcare Finnamore

This article was first published in August 2016.

No comments yet