The theme of this blog series is how thinking like a social movement leader might help us to strategise for transformational change in healthcare. For me, one of the most powerful shifts has been in the way that I think about resources for change.

In our classic approach to strategic planning, we regard resources as sources of support that can be allocated. The typical scenario is one where leaders make available a finite amount of resource (a “resource envelope”).

‘Rather than allocating resources, social movement leaders have to build them’

This resource might take the form of monetary funds, people, management support systems and/or technology. Leaders then make allocation decisions on the basis of their strategic analysis; where the resources should be best placed to deliver the changes required or make real the opportunities that they have identified. In this context, resources are finite and they diminish over time. Once the resource envelope has been used up, it is gone, unless the leaders can make an organisational case for additional resources to be allocated.

Strategic resourcefulness

Let’s think about resources for strategic change from the perspective of social movement leaders. Commentators like Marshall Ganz tell us that since such leaders generally don’t get access to the kinds of resources that organisational leaders have available, they have to be “strategically resourceful”. Rather than allocating resources (which they don’t have to start with), they have to build resources.

These resources are typically made up of relationships and commitments to a shared purpose. They happen as a result of discretionary effort or discretionary energy. People get engaged in the change because they make an emotional connection with it, linked to their values and really believe in its goals. They are willing to take action because they want to, not because they have to.

In my experience, this resource mobilisation mindset applies as much to organisational settings as it does to social movements. Research conducted by the Corporate leadership Council revealed that leaders who trigger emotional engagement release 400 per cent more discretionary effort than those who trigger rational engagement (that is, get people to engage in change because they believe that the goals are in their self-interest).

I’m going to say more about relationships for change in my next blog, but it is suffice to say here that the more we adopt this “social movement” mindset, the more we create the possibility that resources for change can actually growwith use, rather than diminish. A good recent example of this is “The Right Prescription” a nationwide call to action to reduce the inappropriate prescribing of antipsychotic drugs to people with dementia. It’s the topic of a research report that Manchester Business School has undertaken for the NHS Institute for innovation and Improvement: Mobilising and organising for large scale change in healthcare: ‘The Right Prescription: A Call to Action’. Look out for the report, which will be available electronically in the next couple of weeks.

Overall, across England, there has been a 51 per cent reduction in prescriptions of antipsychotics for people with dementia which, given previous indications of the massive problem of overprescription of these drugs and the tragic consequences for the people involved, is a great achievement. While it cannot be claimed or that this improvement is a direct result of The Right Prescription in a cause and effect manner, key stakeholders regard it as an important contributory factor.

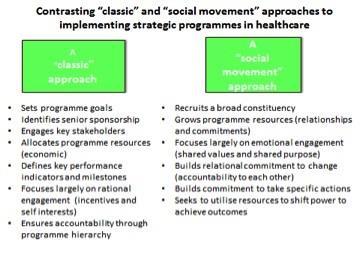

The contrast between a “classic” programme approach and the approach to change adopted for The Right Prescription is shown in the diagram below.

If a “classic approach” had been taken for The Right Prescription, the focus would have been on changing the prescribing behaviours of doctors, through a variety of mechanisms relating to compliance with standards, prescribing guidelines and financial incentives to change. Instead, a “call to action” methodology was adopted, based on social movement principles.

The NHS leaders of the programme formed a strategic partnership with the Dementia Action Alliance, a confederation of more than 100 organisations across multiple sectors that are united by their mission to improve the situation of people with dementia ad their carers. As a result, eight different groups of people were identified who could take action towards the goals of the programme. These included people with dementia, their carers and the voluntary sector organisations who support and advocate for them; pharmacists and leaders of care homes as well as the clinicians who prescribe. Each group was helped to self-organise.

Each group defined their own goal and specific actions that they wanted people in their category to take and by when. So, for instance, the pharmacists’ goal was (in partnership with prescribers) to review everyone under their care who had been prescribed antipsychotic medications. The pharmacists group then identified specific actions that they wanted community pharmacists and hospital pharmacists to take towards this goal and mobilised their pharmacist colleagues to take these actions.

Perfect prescription

As a result of this approach, The Right Prescription felt “done with”, linked to intrinsic motivation for change, rather than “done to”, driven by compliance with an external goal.

The research report identifies the success of this approach in growing resources for change. The relationships that were built and the commitments made have led to another effective call to action, “The Right Care”, focused on improving the care of people with dementia in acute hospitals and has helped the Dementia Action Alliance to grow into an effective force for nationwide change, promoting dementia-friendly communities.

The key shift in strategic logic here is that we, as healthcare leaders, can break out of a narrow view about available resources for change. Resources for change are abundant and everywhere; they are in our own organisations, our partners in local health and healthcare settings, our communities, the wider social sector and in the people we connect with through social media and our professional networks.

Some questions to consider:

- How can we as leaders be “strategically resourceful” and call to action the potential resources that are available to support our change efforts?

- How can we build the discretionary effort of our own workforce through emotional engagement with a shared purpose and an “us and us” rather than “us and them”?

- Given that most of the economic resources of the NHS are locked up in the current ways that we deliver care, can we unlock (additional kinds of) resources to support and deliver the transformational changes we seek?

For more resources on large scale change, follow Helen Bevan on Twitter @helenbevan

No comments yet