HSJ’s expert briefing on NHS finances, savings and efforts to get back in the black. By finance correspondent Henry Anderson.

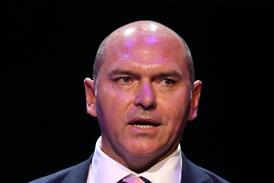

Last week Simon Worthington, the finance director of Leeds Teaching Hospitals, retired after more than 20 years as a financial leader in the NHS.

The departing executive, who started his career in 1988 as management trainee at Leeds West Health Authority, spoke to Following the Money about his time at the city’s trust and how the finance profession has changed over those years.

Mr Worthington took on the role at Leeds in 2017, a year after the organisation had recorded a £30m deficit. Since then the trust has delivered seven consecutive years of budget surpluses, something which is becoming vanishingly rare in an acute sector characterised by deficits.

This was achieved by devolving decision making to clinical teams and asking them to solve problems, he said, but also by framing efficiencies differently.

He says: “We talk about waste reduction. Removing waste from processes cannot harm patients. We had our biggest year of waste reduction ever last year, and our staff survey went up. Patient quality indicators were fine, and going up, and our waiting times coming down.”

The assumption clinical teams aren’t interested in money is absolutely “not true”, he adds, highlighting the use of the “Leeds improvement method” and recasting the problem as how to deliver the best services within the financial envelope.

“As a finance director, you can’t be the enemy of quality… if you see them as separate, then you’ll run into difficulties… [it’s about] empowering clinical colleagues to improve their work, engaging them in the problem.

“The problem is, we’ve got to deliver great services for patients… the government have decided this is how much money we’ve got to do it with – and that is a lot more money than we had a few years ago.”

Before taking on the job at Leeds, Mr Worthington had a four-year stint at Bolton Foundation Trust, where he was part of the organisation’s turnaround (telling HSJ at the time he ignored many of the accepted rules for struggling trusts) and for which he was named as the Healthcare Financial Management Association’s finance director of the year.

When he joined, there were fears that up to 500 staff would have to be made redundant due to its financial problems.

He says: “We did have to have an organisational change programme, but it was nowhere near 500 people. You don’t want to get in that position. If your local hospital’s got a big deficit, that affects patients in various ways.” When a trust has “a big deficit, it’s in turmoil, it affects the mood of the staff”, he added.

But he argues the way the NHS manages its finances can push boards towards deficit plans.

“It’s too easy to say ‘I’ve said it’s impossible, we’re going to have a big deficit’. It’s a comfort zone, isn’t it?

“As a finance director, if you say to the board – which you shouldn’t – ‘we’ll balance, it’s all fine’, and then end up with a big deficit, you very often get the sack, so there’s a feeling that ‘I better say we’ll have a big deficit’.

“There is a little cultural thing where you feel more safe as a finance director… To have a surprise deficit is worse than having a planned deficit.”

But he said, even though trusts are generally not allowed to accumulate and spend surpluses, there were “all sorts of positive reasons why your organisation wants to balance, or have a surplus” – such as staff and patient confidence; and demonstrating that the organisation is financially sustainable.

He added: “It’s very challenging in the current environment. But that doesn’t mean it’s impossible.”

Finance profession is ‘one big team’

The working environment has completely changed since his early days in the NHS, Mr Worthington says, recounting a period as a junior manager when he and his colleagues were banned from talking about non-work matters in the office.

He pays tribute to the work of One NHS Finance as a big part of what he sees as a positive cultural shift. Now eight in 10 trusts have at least level one accreditation from this programme, demonstrating their commitment to supporting and developing finance staff.

Its other initiatives include a demystifying finance programme for clinicians, and a talent development programme which has supported more than 40 deputies into executive roles.

Mr Worthington chaired the Future-Focused Finance programme, which promotes the range of careers on offer and attracts new people into the profession.

Now he says there’s a feeling that the profession is “one big team”, in a marked departure from the heyday of autonomous foundation trusts, where finance leaders at the helm of a newly minted FTs would proudly announce they were no longer attending meetings with other providers. “You had people isolating their individual organisations, in silos,” he says.

“[Now] you’ve got a whole network of people that you can get hold of to find support, whatever the issue is… the finance function in the NHS has got the best development process for its staff than any of the other professions.”

Bringing in the Big Four

NHS England’s latest effort to keep a lid on deficits – sending consultants in to carry out an “investigation and intervention” exercise – is reportedly prompted by concerns that the nine systems on the list are already off plan at month two (surprise, surprise) and in danger of overspending their full-year budgets.

How this fits into the new government’s stated wish to slash consultancy spending is less clear.

At first glance much of the initiative – reviewing grip and control, the development of efficiency plans, the effectiveness of project management offices – look fairly basic, prompting questions about why this wasn’t being done already.

One local source said it was “helpful to get assurance on [the] effectiveness and impact of existing controls and delivery of current plans”, and said their existing work would now have a greater pace and weight thanks to NHSE’s involvement.

A CFO in a different system welcomed that NHSE was at least giving the nine integrated care boards the freedom to commission the consultancy work themselves, and tweak it locally, giving a degree of local ownership.

Sources said the planned deficit across trusts and ICBs had been cut to around £2.2bn by the new system of control totals signed up to on 12 June.

Documents outlining the new programme stress the importance of each system hitting its control total, suggesting NHSE has found a way – however painful – to cover off the local deficit with central underspends.

But that comes ahead of winter and the likely cost of trying to keep emergency care under control; potential further strikes to cover; and pay deals which may or may not be fully funded.

And, for NHSE to act this early – coming just a month after it unveiled a new financial regime – is an indicator of the deep concern that this year’s financial outlook must be causing.

3 Readers' comments