In light of the extra £20.5bn NHS funding, Anita Charlesworth outlines the various cost pressures that will likely consume most of the extra funding before improvements in quality and access can materialise

When the prime minister announced an extra £20.5bn for the health service in June this year, she tasked Simon Stevens with the development of a long term plan by the autumn.

That plan will cover ambitions for improvement over the next decade and delivery of progress for the next five years of the funding settlement. As the HSJ recently reported, more than a dozen working groups are now being established to work on that plan.

Time is tight and as the working groups get underway, it’s clear that they have a major challenge ahead of them. The extra money is clearly very welcome.

However, while substantial, it is just enough to maintain current levels of quality and access, and below the estimates of funding growth required to improve and modernise the NHS.

The extra money is just enough to maintain current levels of quality and access, and below the estimates of funding growth required to modernise the NHS

Healthcare spending pressures are growing by 3.3 per cent a year just to maintain current service standards.

To improve and modernise care would require spending growth of at least 4 per cent a year, while the prime minister’s announcement is for 3.4 per cent.

How can it be that such a huge amount of money isn’t enough?

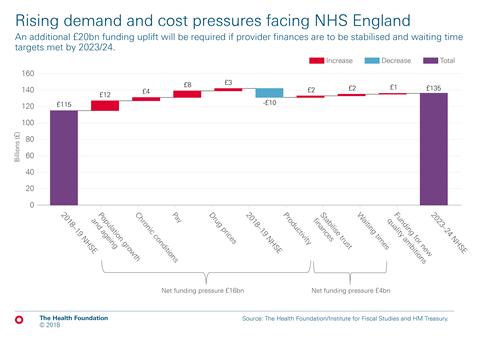

The chart below shows how the demand and cost pressures faced by NHS England will consume most of the extra funding over the next five years.

New pressures

There are new pressures from a growing and ageing population with a rising burden of chronic disease. While a growing and ageing population will add £12bn to NHS pressures, chronic disease and particularly, multimorbidity adds a further £4bn.

In 2015-16, one in three patients admitted to hospital in England as an emergency had five or more health conditions, up from one in 10 a decade earlier. The pressures on hospitals from patients with multiple chronic conditions has risen rapidly over the last decade. If that trend continues, hospital activity would increase by 14 per cent over the next five years.

The NHS also faces input cost pressures from pay and rising pharmaceutical costs for new, innovative medicines. A significant proportion of the increased funding will be needed to meet the cost of real terms pay increases for NHS staff.

While a growing and ageing population will add £12bn to NHS pressures, chronic disease and particularly, multimorbidity adds a further £4bn

After seven years in which NHS pay has not kept pace with inflation, the government and unions have agreed a new pay deal for Agenda for Change staff and, just before the Parliamentary recess, a doctors and dentists deal. Together, pay and pharmaceuticals add at least a further £10bn of cost pressures.

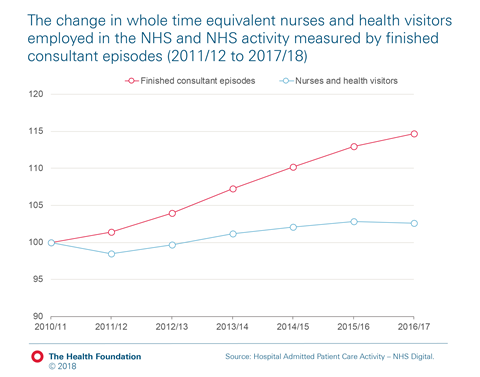

Staff shortages pose a very substantial risk to the health service’s ability to sustain high quality care. The chart below shows what has happened to the number of nurses employed in the NHS compared to growing demand.

Nurse numbers have increased by just 2 per cent while hospital inpatient activity has grown by 15 per cent over the last six years. Meanwhile, one in 10 nursing posts are unfilled.

Productivity improvements can offset some of these pressures – productivity growth of 1 per cent a year would reduce spending pressures by £9bn. But taken together, additional demand and rising input costs can’t be fully offset by productivity growth.

Even with productivity growth, additional demand and input cost pressures will consume three quarters of the extra NHS funding promised by the prime minister over the next five years.

Other challenges

In addition to these new pressures, the health service has further challenges that will require funding; NHS hospitals are in deficit and aren’t meeting waiting times targets for accident and emergency and planned operations.

The health service has been transferring money from its capital budget to bridge some of the gap. But despite this, four in 10 NHS trusts ended the year in deficit and were reliant on a range of one off temporary measures to manage their finances.

NHS Providers estimate that stabilising NHS trusts’ finances might require up to £1.8bn of extra funding.

The Health Foundation and the Institute for Fiscal Studies estimate that treating all A&E patients within four hours and meeting the 18 weeks target for planned care would add £2bn to the cost of care in 2023-24.

Addressing the problems of NHS trusts’ financial deficits and waiting times would require almost all the remaining funding growth over the next five years. This leaves less than £1bn of the additional £20.5bn of NHS funding for genuinely new improvements to quality or access.

Addressing the problems of NHS trusts’ financial deficits and waiting times would require almost all the remaining funding growth over the next five years

The newly approved £20.5bn is a substantial increase in NHS funding but working through the numbers, the money offers no easy route to improvements in quality.

To create some headroom to change and improve the NHS offer, something is going to have to give. The obvious area to look at is waiting times.

There is a clear logic to reviewing the approach to waiting times so that some of the extra funding can be “freed up” to invest in transformation or new areas of quality improvement.

Added to that, the ongoing workforce issues, particularly around nursing, raise real questions about the practicality of making quick progress on the 18 weeks target in particular.

4 Readers' comments