Learning from past mistakes can be as instructive as successes. Could reminding ourselves of NHS failures be more liberating than ‘positive thinking’, asks Craig Barratt

In Ann Arbor, Michigan, there is a vast museum. It is not open to the public and it holds only one of each item. This is no ordinary museum, for the tens of thousands of household products on its walls and shelves are failures.

Oliver Burkeman, in his book The Antidote: Happiness for People Who Can’t Stand Positive Thinking, describes them as “products that have been withdrawn from sale after a few weeks or months because virtually nobody wanted to buy them”.

How can we learn from past failures in the NHS? Join Craig Barratt for a Twitter chat on 4 October at 1pm #HSJChat.

It is colloquially known as the museum of failed products and, according to Burkeman, it is a result of the fact that “most products fail” − his estimate of the failure rate being as high as 90 per cent. Originally intended to be a collection of all consumer products, it necessarily became about failure reflecting the real world.

‘The national IT programme would take pride of place, showing how technology can be overengineered to the point where failure is inevitable’

Started in the 1960s and operated by a firm called GFK Custom Research, it contains products such as Clairol’s Touch of Yoghurt shampoo. This is not intended as a place of curiosity and amusement though. This is a lucrative profit- making business. Premium prices are charged to product developers who want to revisit past failures in order to avoid repeating them.

A fascinating insight from Burkeman that should strike a chord with the NHS is that visitors are not necessarily visiting the past failures of others. In a number of cases, they are seeing the failures of the companies they work for.

Their own companies, obsessed with success, do not dwell on the past and product developers, perhaps unsurprisingly, have not heralded and preserved their failures as they move between companies.

Curating the NHS collection

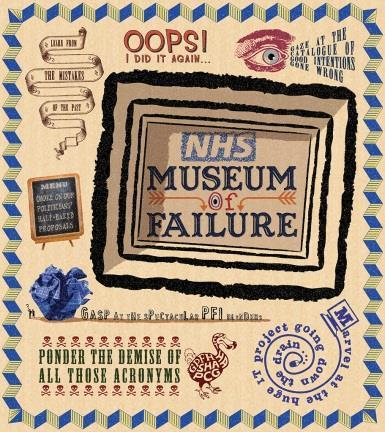

Naturally my thoughts turned to what an NHS Museum of Failure would look like. I quickly visualised long corridors stretching into the distance fully packed with exhibits.

The national IT programme would no doubt take pride of place, with an enthusiastic staff member offering samples of how technology can be overengineered and suppliers screwed to the point where failure is inevitable.

We could have a whole room for the organisational acronyms that have come and gone such as PCTs, HAs, SHAs, GPFHs and PCGs.

‘Where failure occurs at a senior manager or executive level, the individual quickly reappears in some other part of the system’

The Capital Developments corridor would be stacked to the rafters: the cardiac centre built on the coast without the population to sustain it; the private finance initiative hospital with too few beds; the publicly funded, state of the art primary care centre generating profits for resident GPs; and the teaching hospital with some departments that feel like a five star hotel, while others would shame third world countries.

Glass cases would be filled with the good intentions of commissioners, admissions avoidance schemes and perhaps a selection of human resource contractual failings: the GP contract, the consultant contract and Agenda for Change.

There needs to be space for those personal and local failings though. The failure to turn a bed-bound patient, resulting in pressure sores; the food left in front of the patient who cannot feed themselves; and the junior doctor that is so tired from his European Working Time Directive non-compliant shift that he overprescribes a medication tenfold.

The gallery cafe would naturally contain the half baked ideas of politicians and their whimsical interjections into complex issues with glib and self-interested interference. A small selection should suffice, perhaps including two accident and emergency departments being kept open when there are only enough specialist staff for one, and the PFI hospital that was built on two sites when the patient numbers justified just one.

Capitalism reversed

In the “real world”, where capitalism largely functions without the brakes of excessive bureaucracy, success tends to be rewarded and failure punished. Those at the top in the private sector have had impressive runs of success.

In the NHS, however, this natural law fails to act in a consistent way. Across all grades, the wave of incremental progression up the Agenda for Change pay scales continues undeterred by structured and challenging performance management.

‘We need to enthusiastically embrace the breadth, scale and frequency of failure at a national, local and personal level. We need to live and breathe the failure’

The harsh commercial reality of “up or out” is perverted to become “up or up”. Where failure occurs at a senior manager or executive level, and the individual is unfortunate enough to not qualify for the holy grail of early retirement, they quickly reappear in some other part of the system.

The result of of this means, if we can only encourage our people to speak openly of failure and ourselves to listen, it can be our primary source of learning. One of the NHS’s greatest failings can be one of our greatest opportunities.

In my personal life, learning from my past failures is an ever present. Every day I wake with the intention of avoiding the mistakes I have made. So why do I not take the same approach in my professional life?

In my former consulting career, an exercise that stands out in the context of fully embracing failure is pre-mortems − a simple workshop exercise I have carried out with numerous groups about to launch innovative transformation projects. In the sessions we seek to actively visualise what failure will feel like in the future.

We project ourselves into the future and look back on the failure of the enterprise that has yet to be launched. I have, on occasion, even drawn the figurative cadavers of the project so that we can physically label the past reasons for failure that has not yet occurred (think knees labelled with lack of flexibility, eyes with lack of vision and the heart for lack of passion).

Positive thinking

For fans of positive thinking, this may seem anathema. Surely we need to think of how successful we are going to be? If we picture failure, we will fail, right? But it doesn’t feel like this in practice. The experience is often a liberating one. People bring to this exercise their experience and knowledge of past failings, unconstrained by the need to revisit or confess their role in them.

This exercise will not turn a doomed project into a success (these should be stopped at this stage regardless of sunk costs − human and financial), but it will give a shared sense of ownership and an opportunity to focus on collectively planning to avoid known pitfalls.

We all know people who are more than willing to relentlessly examine and advertise the failures of others. The press appears to treat it as a national sport. This is not what the museum is about. It is not an exercise in the kind of sneering and knowing cynicism we are all too familiar with in the NHS. Nor is it a superficial willingness to talk about failure as a shortcut to success.

‘Embracing the lessons from failures does not mean we tolerate teams or individuals who are destined to fail’

We need to enthusiastically embrace the breadth, scale and frequency of failure at a national, local and personal level. We need to live and breathe the failure. Only then will we realise the scale of the challenge and the complexity of the environment we now work within. Our ambitions and approaches to solving the problems we face should be shaped for this new reality.

The museum of failed products demonstrates that it is commercially astute to collect and revisit past failures, regardless of whether these are the failures of others or our own. We need to be cautious though; embracing the lessons from these failures does not mean we tolerate teams or individuals who are destined to fail.

We need to ensure we only employ people and create teams that have the character and competence to embrace failure but deliver success more often than would be expected.

So, to the important question: who shall we select as our curator? We’re looking for someone with an intimate knowledge of NHS failure over the last 30 years and a passion to improve it. With a planned opening date of April 2014, I’d appreciate your thoughts on who might fit the bill.

Craig Barratt is executive director of transformation and innovation, Lancashire Care Foundation Trust

3 Readers' comments