Conversation about the future of the NHS tends to focus on the role of clinicians, neglecting the army of non-clinical staff, who remain largely invisible and under-used. HSJ and Serco’s roundtable looked at how things could be made different

Patient experience

Most patients may never become sufficiently expert in their appreciation of clinical care that they can easily assess whether what they have received is good or bad. (Patients do know when they experience poor or rude communication, which as UK studies consistently show is strongly associated with doctors being sued).

Many aspects of patients’ experience of care which they can understand and relate to their experiences of other organisations are directly those of the non-clinical workforce, as Paul Myatt, workforce policy lead for NHS Providers, points out.

“In terms of ‘happy’ patient experiences of receiving care, much of this is influenced by the person on reception, such as whether systems work properly, whether clinical staff have the right information, is the environment clean? (And of course, car parking!)

Patient experience, as opposed to more narrow clinical outcomes, is a big contributing factor to how people think of their experience of care”.

Getting these service-type aspects consistently right contributes not only to patient-centred care, but also to making the working environment more agreeable for staff.

A clean, well-maintained and calmly run atmosphere and environment will be more likely to achieve the win-win of inspiring confidence in patients and having a positive effect on staff morale.

Why non-clinical staff are undervalued

Paul Myatt pointed out that in the wake of the Francis inquiries into Mid-Staffs, the regulatory and political emphasis on safe levels of clinical staffing has taken workforce directors’ attention.

“Clinical staff numbers are what regulators come and count. So in the main, HR directors’ attention is paid to clinical staff: if their organisation lacks enough of them, there are impacts immediately for quality, regulation, media attention – and of course, poorer outcomes”.

All participants in the workshop for this interim report agreed that another key factor was a reluctance to describe the value of “backroom” non-clinical staff, informed by political and media hostility towards NHS bureaucracy and bureaucrats.

Unison’s deputy head of health Sara Gorton suggested that “we’ve become reticent to talk about the budget spent on non-direct patient care. We’ve collectively failed to make the case for the value of this work and workforce, when actually it’s the way we can help improve productivity.

“I recently had treatment at King’s: I thought I’d get good clinical care (and I did), but what most impressed me was the admin systems support. The care was across four or five departments, and it was very obvious that their administrative managers were talking to each other, and understood how the other departments worked”.

Non-clinical support staff are vital to all services, but I don’t think they’re often remembered by policy makers

Managers In Partnership chief executive Jon Restell agreed that a perceived threat of Daily Mail-type manager-administrator-bashing “has made us reluctant to draw attention to the non-clinical care spend.

And there’s lots of good work to promote: from the porter who makes time to talk to a frightened patient to the clinical coders and finance staff – we should value these as important occupations, as well as simply being jobs”.

Skills For Health head of research and evaluation Ian Wheeler pointed out that under-valuing non-clinical staff “is part of the whole discourse of the Andrew Lansley agenda of the last six years, about getting rid of backroom staff, who have been framed and perceived as waste.

“And that’s ludicrous: without good non-clinical colleagues and their systems, clinicians won’t know who they’re supposed to be treating for what and when”.

Mr Wheeler added that his impression is that non-clinical staff increasingly feel like outsiders: “they don’t feel they’re being listened to, and feel they’re being bypassed in conversations about change.

Which is bizarre, because many non-clinical staff are very experienced people, who’ve been in this sector for a long time, and who know how to make change work successfully. And they know what doesn’t work, too”.

Fundamental benefit

In terms of presentation of the NHS, director of workforce for University College London Hospitals Foundation Trust Ben Morrin observed that it can be attractive to focus on brands which are easier for the public to connect with, such as doctors and nurses.

He added that there are various other unhelpfully “broad brush” and negatively-framed names in the field, like professions allied to medicine and allied health professsionals “which were scarcely appropriate for the healthcare delivery of 1996, let alone 2016. We need to be clearer about our language for describing people who provide services of fundamental patient benefit”.

Dean Royles, director of HR and OD at Sheffield Teaching Hospitals Foundation Trust, and former chief executive of NHS Employers, concurs with the bureaucracy-bashing analysis: “once non-clinical staff become a professional part of the workforce, they get lumped into a populist demonisation of bureaucracy, ‘oh, they’re not front line, so they’re not essential to NHS running’.

“To get the best out of this part of our workforce, we need to present this as an area in which people would want to work. So we have to get the national PR right about these jobs, and that ranges from thinking fully about talent management, job desirability, down to things as basic as having the right job descriptions”.

Mr Royles concludes that “non-clinical support staff are vital to all services, but I don’t think they’re often remembered by policy makers. What would help would be to highlight more those non-clinical support roles as central to patient care. These are jobs where people should be valued, get satisfaction and in which they can train and develop careers.

“Many of us know that in the NHS we have great access to training and development opportunities, but wouldn’t have known this from outside the NHS. So this needs to be communicated: non-clinical staff make a big contribution: they’re not bureaucrats, time-wasters and pen-pushers”.

Andrew Prince, development director of the Serco Global Healthcare Centre of Excellence and a non-executive director of Frimley Park Hospitals Foundation Trust, observes that “the metrics still tend to be about cost rather than value: the Carter efficiency review data on the cost of a meal per head, rather than the value to a patient’s wellbeing and recovery of a good quality meal and its contribution to a swifter ability to leave hospital. Likewise, we tend not to get data on the relationship between cleanliness of acute settings and prevented infections.

“So we’re yet to connect the value of some of these non-clinical roles with clinical value. Until we can make that connection, decisions will be all about cost, and not about how to use the valuable resource of these staff”.

Paul Myatt agrees that the case for the value of this part of the workforce should be made more strongly: “We should say that improving your non-clinical support workforce could make your (expensive and scarce) clinical staff more productive with efficient administration – getting the right level and quality of staff to support your clinicians to do great jobs”.

If we want to ‘Get Carter’ we need to get the value of support and non-clinical staff - Paul Briddock

MIP’s Jon Restell reflects that the real need for better appreciation of these staff is among those charged with workforce planning: “intermittently, we discuss with Health Education England the 0.01 per cent of the NHS training budget for non-clinical staff, and depressingly, nothing changes.

“Look through the vanguards’ work and the Carter efficiency review: it’s riddled with requirement for skilled non-clinical staff in procurement and integration. Where is a supportive plan for developing and retraining those staff, in the way you’d have for clinical staff if you were redesigning cancer services?

”One of the vanguards’ staff pledges was that ‘we will engage clinicians, on values of programme’. Just engage clinicians? Until that changes, we’ll make little headway with politicians or others”.

Healthcare Financial Management Association director of policy Paul Briddock agreed that “a great deal of what’s needed to achieve the Carter efficiencies is highly-skilled work. If we want to ‘Get Carter’, we need to get the value of support and non-clinical staff.

Visibility and integrating teams

Sara Gorton described Unison’s attempt to increase the visibility of this staff group: “our ‘One Team’ campaign was about getting members in non-clinical roles to describe to clinician members what they do, and large numbers said that their colleagues in their own trust had no idea what they did and what their contribution was”.

Ben Morrin highlights UCLH’s efforts to get an integrated ethos among staff from the point of arrival: “2000 staff join us each year, and in their first week, all the different groups come in together, and sit together at lunch and dinner, and talk together. Which helps a lot, but is only the start.

“Another priority for us is to share and champion great administration’s contributions; it’s about showing the value at its point of impact. So when we successfully recruit 700 nurses that we need, we’ll celebrate that success with those who benefit.”

Serco’s Andrew Prince suggested that part of solving the value and visibility issue might be to get patients to help us explain this group’s importance.

“Quite a lot of these staff have expensive contact with patients – cleaners and caterers are always around, and can and do give exceptional service. Patients write in sometimes, and say ‘that porter was really caring, and went above and beyond the call of duty’, and maybe we need to lift that feedback into more public use”.

Feeling valued

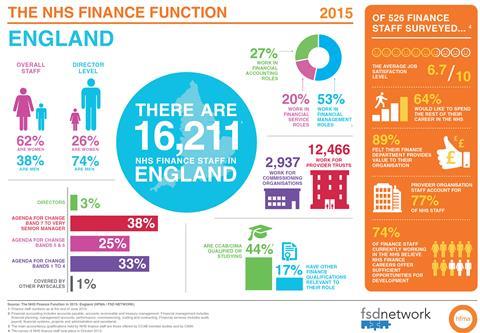

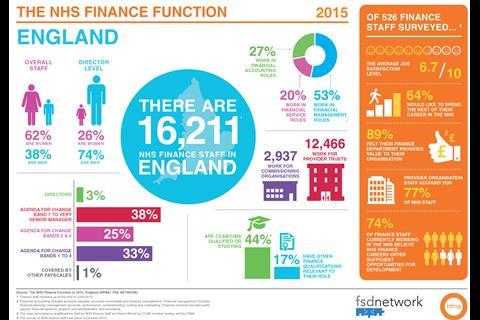

Paul Briddock presented startling data from their recent finance staff census and members’ survey.

While 89 per cent of respondents felt they did a valuable job for their organisation, answers on how they felt valued were stark. Seventy-eight per cent felt valued by their line managers; 48 per cent by the board and 46 per cent by clinicians.

When responses moved to what government, the public and patients think, 10 per cent felt valued by government and 5 per cent by patients.

Finance staff reported high levels of motivation: 71 per cent saying that they really value working in NHS and public sector ethos and 60 per cent saying that they see their primary role as trying to improve patient care.

Yet while 64 per cent say they would like to spend the rest of their career in the service (despite mounting pressure on their teams and the most challenging financial operating environment to date), many fear that the constant change and reforms mean they won’t be able to fulfil these ambitions, with only 47 per cent expecting they will continue to be employed by the NHS until they retire.

Workforce planning

The NHS consistently has what we might politely term ‘issues’ with clinical workforce planning, and much the same is true of the non-clinical workforce.

Dean Royles says there is “no strategic oversight of the non-clinical workforce (which goes well beyond support roles, if we think about engineering and IT).

“This is a non-commissioned workforce. This is about half of the NHS workforce, and it’s one where by and large, the market dictates supply and there are professional regulations, training and qualifications in such fields as HR IT, finance, etc.

Part of solving the value and visibility issue might be to get patients to help us explain this group’s importance - Andrew Prince

“For clinical staff, our efforts to predict workforce have tended to see us lurch from problem to problem as the care delivery model changes. Planning of that kind has not really happened in the non-clinical workforce: you do get some specialisms, such as IT, but the market responds relatively quickly to changes in demand”.

Unison’s Sara Gorton reflects that “rather than celebrate jobs and roles, perhaps we should celebrate skills. It’s interesting that in the NMC vanguard work, what’s at the forefront is moving away from traditional specialist roles: not from specialist to generalist, but expecting mutli-specialisms.

”The parallel ability for non-clinical colleagues to analyse, change and influence, whether in rostering, setting up payroll, changes in OD: these are all skills we can describe, and maybe that’s an important labelling job”.

Scarcity and career desirability

Dean Royles’ view, informed by his time running NHS Employers, is that policymakers tend to have “a very London-and-south-east-centric belief that non-clinical or support staff are hard to come by: a parochial view of the labour market world.

“So any policies we do get tend to be about how to deal with recruiting people with, say, long-term conditions or criminal records, or the long-term unemployed and those not in education, employment or training.These are very evident in south-east England’s workforce planning, which is quite reliant on a wider EU/ international workforce.

Other obstacles to progress are the quality of appraisals; a dearth of information about NHS productivity, and the consequent failure to link the contribution of good processes, system analyst skills and operation skills

“By contrast, where I work in Sheffield, the non-clinical jobs in the NHS are seen as good, desirable and stable jobs. In Leeds and Sheffield, the NHS has a good choice of staff.

Mystery training

Dean Royles concludes that consequently, “the national policy focus tends to be assuming it’s hard to attract and recruit non-clinical staff, and there’s been very little attention to training and development and career prospects. There’s the occasional bit on apprenticeships.

“The policy landscape is always London-centric, where it is hard to recruit, so we’ve seen very little on encouraging non-clinical staff to move on in their careers with training and development opportunities. It shouldn’t be hard to support. Those in bands 1-4 end up doing 70 per cent of hands-on care”.

Skills For Health’s Ian Wheeler adds that “the cycle of workforce planning often does not take account of clinical support workers, and tend not to receive the training and development they should do.

Skills For Health major in this area, including clinical and non-clinical support staff. In practice, you get what can feel like almost a clinical strong divide, where the clinical registered workforce get a lot of attention.

“Our paper looking at the healthcare support workforce used the labour force survey data to split clinical and non-clinical workforce, and we found some suggestion investment in admin skills in NHS less than in the private sector.”

Skills For Health’s study also found than non-clinical staff receive substantially less training overall.

Without good non-clinical colleagues and their systems, clinicians won’t know who they’re supposed to be treating for what and when - Ian Wheeler

This report also found that “only a quarter of admin and secretarial workers received training and development in the past 13 weeks, compared with almost half of the workforce overall, and a significantly lower proportion of administrative and secretarial occupations are qualified at NQF level 4 and above”.

A second Skills For Health paper, Mr Wheeler adds, analyses the hourglass shape of the workforce: “the healthcare sector is good at developing high-level clinical registered skills, then you have lots of staff at the bottom, and a thin wedge in the middle through which people pass as their careers progress.

”What we need is to expand the high-skilled, flexible and responsive intermediate workforce”.

The NHS is mostly, Mr Wheeler suggests, “not creating high-quality intermediate jobs – where people could be working at a very high-quality level. We consistently see this in the UK economy as a whole, and so unsurprisingly it’s reflected in parts of healthcare, and in the divide between the clinical registered and non-registered workforce.

“Healthcare is becoming increasingly data driven. Who can get hold of, manage and maximise patient data? The processing and flows of this data, going forward, will be increasingly important”.

This presents challenges: NHS Providers’ Paul Myatt observes that some HR directors already complain about challenges in recruiting sufficient IT staff within the pay bandings of Agenda For Change.

Mr Myatt also suggests that employers “should address motivations beyond quality and finance: think about having an engaged workforce; about development opportunities to build careers (including non-clinical ones).

”And we need to be more forward-thinking on patient experience: NHS staff, including non-clinical staff, could perhaps benefit from specific training in customer service skills, so patients feel well-treated rather than brusquely treated”.

Ian Wheeler adds that “without great administration, though it may not stir the passions, most aspects of healthcare are more difficult. So many NHS complaints are customer service-type complaints”.

Gender and diversity

Ben Morrin highlights the importance of remembering gender and diversity and inclusion for this workforce. “Most of the NHS workforce is female, and the majority of junior doctors. (It was interesting that in the contract dispute row, the lead negotiators on each side were men).

”This area is fundamental to workforce development thinking. If the same old faces try to design the workforce of the next 10-20 years, it may not be different enough”.

Paul Briddock notes that while 62 per cent of the NHS finance workforce is female, only 26 per cent of finance directors are female, and Ian Wheeler adds that support workers are more likely to be part-time (and women are statistically more likely to work part-time).

Working differently

The workshop session focused attention on how changes in the NHS landscape may affect this staff group. UCLH’s Ben Morrin says that the impact of the Carter efficiency review’s proposed administration spending cap of 7 per cent by 2018 and 6 per cent by 2020 implies an urgent need to review how organisations collaborate and work together.

“Can London’s NHS justify having 80-90 HR departments? Probably not… they’re likely to be fewer and bigger shared functions, which can mean a better service for patients. The STP footprints also imply some potential reconfiguration.”

Unison’s Sara Gorton suggests that “widening the NHS employment footprint could work on many fronts. Some specialist functions like IT may benefit from going to scale. The Carter recommendations need skills to drive technological innovation, like e-rostering and proper booking systems.

“Those kind of functions don’t need either to be small nor England-wide: we’ll need to find a balance. That begs the question of how we get buy-in to participate over wider footprints, and give staff the security they need. Many of our members talk about their fears of instability, of cuts, of services contracted and moved, and that funding streams might just dry up.

“The ability to move some money around in the new STP footprints may free things up and allow bolder decisions. Perhaps there’ll be new conversations with staff, where employers may say ‘we can’t say where you work in five years time, but we know we’ll need your skills, so we will guarantee you work if you’ll commit to stay with us’?”

“If we ask staff to give up their own, known team to run services differently and at greater scale for a population, it comes down to trust in line management and individual managers, and ultimately in the chief executive. Without that trust, plans for change will be deeply flawed.”

Ben Morrin suggests that “if we map the contributions of these staff, we could show positive changes to care pathways and outcomes. UCLH is a clustered organisation: run by clinicians, led by four medical directors, and it’s the most empowering place to work – a big part of which is the quality of respect and commitment to roles that we’re discussing here.

”This is about trust, which depends on the quality of personal relationships, line management support, and being there when team members have tricky moments.

On building sites, it’s a requirement to speak up if you see unsafe practices

“However provision will be organised in future, we should recognise that if we ask staff to give up their own, known team to run services differently and at greater scale for a population, it comes down to one point: trust in line management and individual manager, and ultimately in the chief executive. Without that trust, plans for change will be deeply flawed.”

Skills For Health’s Ian Wheeler adds that other obstacles to progress are the quality of appraisals; a dearth of information about NHS productivity; and the consequent failure to link the contribution of good processes, system analyst skills and operation skills.

Serco’s Andrew Prince reflects that we lack clarity about the required skills. The skills needed for traditional and notionally competing healthcare FT-type organisations are more decentralised ones: those needed to redesign provision across the 44 STP footprints are more integration/transformational skills; yet Carter envisages centralising, efficiency-driving skills.

Sara Gorton adds that this probably means equipping clinical staff with some of the process and change management skills traditionally seen as those of support/admin staff.

“Timing and depth of staff engagement are crucial. All the current big picture changes, even Vanguard innovations, feel as if they’re been foisted on the system from above.

“So some of the skills - transformational skills, ability to lead change without disrupting clinical influence, and be integrators and facilitators of systems – risk being bolted on mid-way.

”There are many good examples of clumsy behaviour of both HR and local trades unions to poorly-thought-through proposals, which could have been thought through and problems anticipated if staff were involved early. It’ll be interesting to see if NMCs Vanguards really engage staff about system design”.

The basis of culture is in consistently clarifying and communicating what organisations value and reward

HFMA’s Paul Briddock reflects that as clinical behaviour and choices drive the vast majority of spending in the NHS, to change these decisions “we need intelligence, and with good-quality information, so we can challenge inappropriate clinical decisions.

“The ‘two sides of the same coin’ work HFMA did with the Academy Of Medical Royal Colleges, NHS Confederation and Faculty of Medical Leadership and Management highlights the need for really good-quality intelligence.

”Non-clinical support staff are the ones with benchmarks, metrics and ability. They are vital to give a solid foundation on which we can challenge clinical performance, outcomes, and also examine patient satisfaction in different ways. Are we providing good value? We need non-clinical staff to be able to answer that question.”

Culture club

All participants agree that over-directive, target-driven NHS approaches forge a negative working culture, too often driven by fear and blame.

Serco’s Douglas Ritchie suggests that changing how we run any system “will fail unless we can change behaviour. You can’t enforce change from policy, you must get commitment to new organisational ways of working and flexibility.

“We have to understand that people deliver all this, and if we don’t tap into their motivations, then behaviours will have an impact on outcomes for patients, the public and staff. Where we work with the NHS, we spend a lot of time with our own colleagues to get the behaviour right.

“My background’s in construction: on building sites, it’s a requirement to speak up if you see unsafe practices, and maybe we need to promote that as a value in the NHS for all staff.”

MIP’s Jon Restell agrees, adding “maybe this inquiry should be not just ‘the nuts and bolts of non-clinical workforce planning’, but could also describe a new, more positive working culture that we want to see”.

Sara Gorton suggested that changing culture and working patterns is also a systemic issue: “by its very nature, commissioning and contract functions are usually in an individual organisation’s best interest to draw close and keep their own identity and competitive edge. Now, we need to share culture across organisational footprints, and get people to work in roles with more utility.

“Maybe we have to think more creatively, as with the Social Partnership Forum work on pensions for a wholly (or mainly) NHS workforce to access NHS pension scheme, and a commitment to some passport for learning skills – more could be done to map this.

“The key for me is to go back to the original NHS Constitution, and reviving those commitments to staff. It may not be politically palatable: the government’s certainly still keen on the constitution commitments to patients and the public.

“But our debate suggests that we probably need well-designed jobs, and opportunities for skills and development. We need to look at the people who’ll be potentially running the system in 20 years’ time, and say ‘these are some of the skills you’ll need, these are where you can find training and help, and we’ll move you around the system in your career to benefit you with the right experience’.”

UCLH’s Ben Morrin suggests that “the basis of culture is in consistently clarifying and communicating what organisations value and reward. For this part of the NHS staff community, and perhaps for quite a bit of it, it seems we’re not quite there.

”The culture we’re seeking locally and nationally needs to be informed by our description to the wider community of the health and care outcomes we want. Local government’s had to be innovative at doing this.

“Secondly, we need conversations about the way to unite the local focus of culture of my organisation, as we seek to balance in our part of the London STP footprint, but also to contribute and inform the national culture – pay development, training, learning, people management 2015-20.

“Staff need to be open when they see bad practice and do something about it without fear. When that’s in place, that’ll be a sign of a good culture: when someone’s done something wrong, staff won’t just throw their hands up and walk away.

”In my part of this workforce, we regard supporting and promoting those who confront bad practice as just decent line management, which we think is as important as patient experience.”

By its very nature, commissioning and contract functions are usually in an individual organisation’s best interest to draw close and keep their own identity and competitive edge

HFMA’s Paul Briddock adds that “a frustration of many of our members is that they feel they’re working in organisational silos. We need to think across pathways, but we’re managed and regulated in organisational silos, and mentally and culturally, once people are in those, it can be very hard to get from one silo to another.

”The old regional health authorities moved staff around like chess pieces to give them broad experience, but after the advent of FTs, we’ve seen that much less.

“That’ll create new challenges: some of the most important finance roles over the next few years will be in commissioning, but the most experienced finance people are in FTs.

”If you’ve only worked in a commissioning background, the move to a provider role is hard. I’m not sure that transferability is there, or that senior managers have given finance staff a much more diverse view of overall system working.

“And there are potential problems with accountability lines through those channels. Bottom-line accountability for providers is to TDA/Monitor, and for commissioners to NHS England. And that causes frustration around joint working.”

Serco’s Andrew Prince concludes that “we need to focus on continuity: the 44 STP footprints are a real opportunity to create new locus of planning and funding transformation to redesign care pathways. How will we reconcile individual financial reporting by organisations with redesigning care pathways across STP footprints?”

UCLH’s Ben Morrin agreed that reconciling these financial and redesign requirements “presents system leaders with a national unlocking opportunity”.

Find out more

Health Foundation (2016) Fit For Purpose?

Skills For Health workforce papers

Acknowledgements

- Thanks for participation in the background scoping, research and workshops for this report are due to:

- Paul Briddock, chief executive, Healthcare Financial Managers’ Association

- Sara Gorton, deputy head of health, Unison

- Dame Julie Moore, chief executive, University Hospitals of Birmingham Foundation Trust

- Ben Morrin, director of workforce, UCLH Foundation Trust

- Paul Myatt, workforce policy lead, NHS Providers

- Andrew Prince, development director, Serco Global Healthcare Centre of Excellence

- Jon Restell, chief executive, Managers In Partnership

- Douglas Ritchie, business development director, Serco Health

- Dean Royles, director of HR and OD of Sheffield Teaching Hospitals Foundation Trust, and former chief executive of NHS Employers

- Ian Wheeler, head of research and evaluation, Skills For Health

About the author

This report was compiled, organised and written by Andy Cowper, comment editor of HSJ, with sincere thanks to all contributors.

Mobilising the NHS’s hidden army

Interim report of HSJ and Serco’s Inquiry into Maximising the Contribution of Non-Clinical NHS Staff

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

Currently

reading

Currently

reading

Maximising the Contribution of NHS Non-Clinical Staff: The forgotten 500,000

3 Readers' comments