It is time the NHS looked outside itself to find different ways of working and look to make progressive improvements that aren’t reliant on funding. By Jo Cubbon

With an ever-increasing demand for care and services, combined with a shortfall of around 100,000 staff, a decade of a slowdown in funding growth and pressures to improve patient safety and experience, the NHS is in a fragile state1.

Change is needed, but how? Following several years of uncertainty, the NHS Long Term Plan (LTP) and five-year funding deal are offering a new strategic direction and hope for the future.

Sponsored by![]()

Extra funding has been secured as a result of the LTP, but it can only go so far. So is it time the NHS looked outside itself to find different ways of working and look to make progressive improvements that aren’t reliant on funding?

Could the success of British sport in the last decade hold the key?

At the World Athletic Championships in September Katrina Johnson-Thompson and Dena Asher Smith won gold medals. Both women took a step back a few years ago following disappointing results. They spent time analysing and understanding their performance in detail and then with that knowledge, hard work and time they rebuilt their performance to achieve what can only be described as outstanding successes.

In the last 20 years, British sport has been on the up. This summer alone England’s men’s team has won the Cricket World Cup for the first time and drew the Ashes, following on from the success of the women’s team two years ago. England are also the only country to have won world cups in football, rugby and cricket. England’s women’s netball team also reached the semi-final of the 2019 Vitality Netball World Cup, winning five out of five matches.

The successes have followed a gradual set of changes in British sport over the years, which have also seen a huge rise in Team GB medal hauls at Olympic events.

From bringing home 15 medals in 1996 (including just one gold) and coming 36th in the medal table, the improvement was steady:

- Four years later in Sydney, the team brought home 28 medals, 11 golds and came 10th in the table.

- By 2012 in London, the team had crept up the table to third place, with 65 medals and 29 of them gold.

- Four years later in Rio de Janeiro, they were second in the table, with 67 medals, 27 of them gold.

During those years, the number of athletes competing both increased and decreased but still the improvement has continued.

While the public only notices the end result, coaches, athletes and whole teams of support staff have been chipping away behind the scenes, making small improvements and using data to achieve the exciting end result that we all see.

The success of the British Cycling Team, under the leadership of Dave Brailsford, brought marginal gains to the fore. One per cent improvement became the norm with the term becoming a watchword for companies outside of the world of sport, looking for new ways of working.

So, could we do that within the NHS? Be patient enough to focus on the small changes that in the end begin to make a huge difference to staff and patients?

The elephant in the room is of course funding. Admittedly, funding within the sporting industry has risen from £5 million of tax payers’ money shared between 27 different Olympic sports in 1996 to more than £245 million (combined funding from National Lottery, the Department of Culture, Media and Sport and some sponsorship) at the Rio Olympics in 2016. The NHS is never likely to find itself with this level of funding increase. However, the money in British sport was not just spent on paying for new athletes; it was used for new coaches and new technology that provided data to enable teams to make small, accumulative changes that generated success over the years, rather than sudden, grand-scale transformation.

But good leadership, the will to perform and the ability to generate data are already there in abundance in the NHS. Could harnessing those factors and looking at the correlation with sport help to generate a culture change and drive performance improvement?

In this article we investigate what the NHS could learn from our sporting success and how to create an environment where marginal gains in improvements, rather than quick-fire broad sweeping changes, become the norm.

Marginal gains and data can lead to improvement

While the NHS and British sport may seem far removed from each other on the face of it, there are parallels that can be drawn between sports and the NHS:

- Good team players on the frontline who inspire one another to perform to their best, who strive passionately for their goals

- Whole teams working together to focus on the same goal

- The use of data to help bring together teams and organisations from across the health economy and to drill down and focus on the areas where change can create improvement

Team work and supporting the support staff

In sport, as well as funding increases there have been other important changes, things that are within our control and not necessarily improved with more money. For example, the importance of looking after, not just athletes and star players, but the whole of the support teams that help to achieve the end goal. Chris Hobson recognised at the NHS Providers Conference earlier in the month the importance of NHS leaders taking responsibility for their NHS staff and not waiting for someone else to take that responsibility.

The NHS can learn from sport through the power of the team and not relying on standout heroes. We know that, in some places, where there is a superstar medic or standout manager, this can get in the way of effective teamwork.

Often in the NHS we have trained senior medics in a model of heroic performance – whereas one of the interesting reflections in the football world is teams that have outstanding star players sometimes don’t perform as well. Look at Premier League teams such as Burnley and Bournemouth who have created a good team ethos despite the odds being stacked against them in terms of financial investment.

The value of support staff in sporting success is readily acknowledged through the vital role that they play in team performance. The NHS often misses the opportunity to make more of NHS support staff and other allied professions. A visit to a trust rated ‘outstanding’ by the CQC, where cleaning staff were given a role in the quality of care: When cleaning staff are on wards they talk to patients and if they have concerns, for example someone who is not communicating as well as they were, they inform nursing staff.

The cleaning team feel really valued and therefore end up being an effective member of an effective team. If you look at professional sports teams the support staff are so important.

Leadership and looking forward

Most agree that culture change is not something that can be achieved quickly. However, good leadership and top-down support of staff and teams is critical.

In the sporting world, talented people are nurtured and supported to do their very best and encouraged to learn from others. The goal is always to look forward to see what can be achieved, while learning from what came before.

Following the 2012 Olympics, Liz Nicholl, who was then Chief Executive of UK Sport said, “We are conscious when people are recruited to key positions as coaches they are not necessarily the finished article in their broader skills. We provide support so that coaches across sports can network and learn from each other. That improves their knowledge expertise and the support systems they have got.”

Two factors seem to underpin Nicholl’s success; understanding how and what marginal gains need to be achieved and belief in and support of very talented people to be able to deliver their best.

Anyone involved in the sporting world who listens to great coaches, knows the emphasis for a winning athlete is to focus forward, to know what goal is to be achieved and plan the path to achieve it. There is an understanding that if the plan falters, adjustments will need to be made to achieve the goal. Of course, if the goal is not reached then analysis is done to understand why, but still the great coaching focus and attention returns to the forward plan, the plan to deliver the goal.

Yet, in health, it so often is the case that the emphasis is placed on understanding and intrinsically investigating failure that has already occurred, with far less time and effort being placed on being able to predict potential failure and take steps to avoid it happening. Once we have an intrinsic understanding of the failure we move seamlessly and without hesitation to need to blame and scapegoat some of our very talented people, clinicians and managers alike.

Well-documented discussions about the time hospital board members spend on discussing safety data or looking at amounts of falls or pressure ulcers is often one of the indicators regulators take comfort in. But should they?

So many of these debates, discussions and healthy challenges that hospital boards engage in are based on what has already happened.

But with good use of data, it is possible to move forward and look at how these challenges can be overcome. Forward-thinking leadership, with good data as a basis for action, can be used as a way to support staff, help to nurture their knowledge and skills and keep them on the right path to the end goal. Having the ability to drill down and focus on certain areas is the starting point for improvement. For example, after Laura Trott won her second gold medal in Rio, she attributed her success to many others in her team, but particularly the nutritionist who supplied her with nutritional data, allowing her to make adjustments to her diet and improve her performance.

The use of data to support and evidence improvement

Data is crucial to providing evidence of where marginal gains can be made and also to show that those gains are creating improvement. However, staff can be resistant to the reliance on data, perhaps feeling it can take away their ability to judge a situation or use their gut feeling.

We know that good data can also help to provide insight and intelligence to develop future plans. Using data can help to engage staff, enabling them to have an overview of the factors that affect their teams and showing them how longer-term, sustainable and cultural change can be driven.

In sport, the performance of some teams have been transformed by the use of data and technology. From the cash-strapped baseball team Oakland Athletics, whose manager Billy Beane used data to identify the best players and saw the team reach the play-offs five times in an eight-year span, to the use of heart-rate monitors and technology that can create a picture of the fitness of players. Beane’s use of data was so revolutionary it spawned the book Moneybags by Michael Lewis.

In the UK, bigger football teams such as Liverpool are now beginning to regularly use data. This year, the club has pulled back from a dismal few years to finish second in the table, thanks in part to data analytics. Traditionally, football hasn’t relied on analytics, but the team’s director of research, Ian Graham, has built his own database to track the progress of more than 100,000 players around the world. By recommending which of them Liverpool should try to acquire, and how the new arrivals should be used, he has helped the club, once football’s most glamorous and successful, to return to the cusp of glory.

Not everyone is convinced by the use of data and some feel football is too unpredictable to make decisions with stats. Indeed, the analytics team at Liverpool can only push the club in the right direction, one recommendation at a time. The information is used in conjunction with advice from other places and so the outcome is a mixture of data and the intuitive.2

While the upper leagues are starting to take data on board, the lower leagues are less inclined. Simon Hallett is Chairman of Plymouth Argyle, recently relegated from League One to League Two. The use of analytics is relatively new to the club, but the hope is to use it more consistently, both to identify the most suitable and best-valued players available in the transfer market and to look at the on-pitch tactics.

Simon is used to seeing plenty of data in his role at his investment company and is hopeful that it can help bring success to the club. He describes the spectrum of data-use in decision making as moving from judgemental (people who like to judge and recognise patterns and think they know how things work) to algorithmic where decision-makers use data to identify causal relationships and hand over to the computer. Ideally, the perfect way to use data should fall somewhere in the middle, he says.

In the NHS, as with sport, it’s important to know what data is needed and what questions need to be answered, so that the appropriate data can be collected. Simon says: “Football is different to baseball, but not so different to other sports. Football is much more fluid than baseball with less one-to-one data, but more similar, for example, to basketball. You need to know what data is going to be important. It’s a bit like that for the NHS. Baseball identified their key data point. With football we’re still struggling to find out the data point.”

He says the key is to find out what is known already, and then find out what they need to know in much more detail so they can drill down further.

For example, when using data to look at pass completion rates, it could look like a footballer makes lots of passes and so is deemed to be good. However, that footballer could just be making easy passes that don’t go anywhere or add anything to the game. In terms of the NHS, this could be equated to looking at a league table of surgeons. While one surgeon could look like they have more deaths than others, it could simply be that they deal with more complex cases. Using data in the wrong way could lead to surgeons not taking on the more complex cases and so patient care would suffer. The analysis and correct use of the right data is more important than just collecting lots of data.

Understanding the benefits of data

Not everyone in sport is a fan of data. This is similar for the NHS, but it is crucial that those with misgivings are able to see the clear benefits to enable moving forward. Simon says: “You have to overcome institutional inertia when you try to do this. It sounds dramatic, but people like to express judgement and often think they are more in control of events than they are.” He says that one of the criteria when looking for a new manager was that they be receptive to data analysis.

If the NHS is to get the very best from the talented people within the health service, then it is essential that clinical teams and other leaders understand the factors affecting the engagement of their teams. The correlation between staff and quality; how the effect of their personal management style can be a powerful factor in creating an environment which encourages and embraces questioning from staff that leads to day to day learning and quality improvement that is team-based, clinically led and engaging.

Staff must be empowered to own their data and to use it, they need to understand how longer term, sustainable and cultural change can be driven. Staff must know how to evidence outcomes, understand the cause and effects, and achieve the marginal improvements for patients.

Case Study 1

Some years ago, an important question was asked at an NHS trust board:

‘We have had three pressure sores in one month’ and, rather than ask the usual question: ‘What caused this?’, the board asked: ‘What could we have done to prevent them?’ – a fundamentally different question and, as it turned out, a very significant one.

The emphasis of the executive discussion that followed was about how the ward and clinical teams could be supported to develop meaningful metrics and collect data which meant something to them and their patients. It was essential to achieve a situation where a ward sister could use the metrics for his or her ward to make changes to avoid harm happening to their patients in the future.

So often the metrics ward staff were asked to collect data that was important to someone else and the data they received was often weeks and sometimes months out of date. For most busy ward sisters this was filed at the bottom of a very large pile and not used by them or their teams. The executive team knew it had the best and most talented people delivering care to patients, but the goal was clear – they wanted ward and clinical teams who were able to predict and therefore prevent harm to their patients.

Having access to the right data is a vital tool in creating change, and used well, can empower staff to objectively articulate their evidence which would enable senior managers and the trust board to make the best decisions for patients with actions that ensured that harm to patients was prevented. Teams that are focused on marginal gains in the care they can give to patients constantly deliver improvements.

The results, of course, were, as always, multi-faceted, but the senior nursing teams believed that due to the visibility of the ward’s performance against all of the operational, people (staffing), and quality measures on a day-to-day basis, the ward sister or nurse in charge of the ward, could make decisions in real time to affect the quality of the care delivered at ward level, so they could deliver those marginal gains for patients.

One of the powerful examples of this approach was the reduction in medication errors. Using the data, the ward teams demonstrated that missed breaks for nurses had a direct impact on medication incidents, i.e. missed breaks = increase in medication incidents. By understanding this, the ward teams took action, advising those who had missed a break that they are likely to make mistakes and so to double check all of their medication. As a result, medication incidents decreased significantly.

Case Study 2

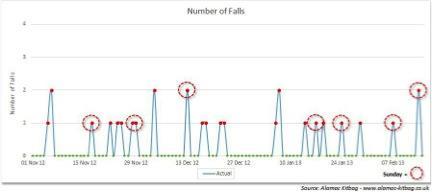

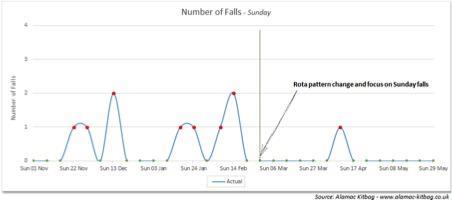

In a Northern Ireland hospital, the first four months of using this approach identified that 33 per cent of all patients falling on the ward happened on a Sunday:

The ward team identified that Sunday was the day in the week with the highest number of agency staff. The rota was changed by the team to reduce the number of agency staff on a Sunday and as a result the numbers of patients falling on a Sunday dropped from 9 to 1, which is an 89 per cent reduction.

Maintaining a focus on staff retention

One of the major issues facing the NHS is workforce and, in particular, staff retention and recruitment. With a staff shortage of more than 100,000 staff, those who are left are taking the strain. Long, busy shifts can lead to exhaustion and a lack of motivation.

In the sporting world, athletes are well supported. They are the main asset and, while the athlete cannot function without the team, there is little point to the team without the athlete. In the NHS, we cannot function without our doctors and nurses and healthcare assistants and should have a long-term plan in place to support, nurture and invest in them.

Chris Hopson CEO of NHS Providers says the NHS expects its staff to work in very difficult conditions without giving them the best working environment and that more needs to be done to support their health and wellbeing.

Mike Farrar is the former chief executive of the NHS Confederation and has spent his career in senior positions within the NHS, including as chief executive of two Strategic Health Authorities. He is also chair of Swim England. He, too, recognises that the sporting world has invested in the long term with academies to help grow and inspire successful sports people and agrees that the NHS needs to look at better supporting its hard-working staff.

Mike says: “In the sporting world, there is a strong ethos of looking after your players. They get support and respite if they have an injury, elite athletes will be pampered. In the NHS, we don’t look after our performers as well as we should. Staff wellbeing is something that is talked about, the need to support people to perform to the best of their ability, but it is something that the NHS needs to work harder at.”

Measuring performance, accurate data and the time factor

With the relentless pressure of a 24/7 NHS, creating time is a factor that organisations often struggle with and it is this that can prevent the ability to look forward and achieve new goals.

Good use of data can be a driver for improved performance and quality of care, freeing up time for staff to see where change can be made.

The NHS differs from sport in that it has less time to focus on where improvements can be made, but an increased use of performance data could free up more time.

A sports person may only be performing for 30 minutes or even just 10 seconds if they are a sprinter. Time is spent leading up to that moment to focus on what they might be able to improve. They will look at fitness and tactics and at tiny ways to make gains. The NHS, however, is constant and is always in play. The chance to stand back and look at how we do things is at a minimum.

To create time within the NHS, the use of data and good analysis is crucial, but better data is needed to take the vital next step to being able to predict when and where demand will be at its lowest and highest.

Recommendations

There is much that the NHS can learn from sport, from focusing on and supporting the individuals who make up whole teams, to finding the small changes that can really make a difference when it comes to patient care.

It doesn’t have to be huge changes, but it is clear that the motivation has to be as strong at the top as it is on the frontline. Staff need to be nurtured, cared for, listened to and supported, whatever their job or role in the team.

NHS staff have seen many changes and many different targets to meet throughout the years. They carry on trying to meet their end goal of saving lives and making people better, regardless of the challenges they have faced along the way.

It is here that the use of good data is vital. Like in sport, it can help to throw a light on areas that could be improved, showing staff why that change should be made and that it’s not just yet another government initiative. It can also be used as evidence to show that those small changes are really making a difference. It can empower the staff to see where they can make change within their own environment and, more importantly, how that small change could have a huge impact on the rest of the health system.

It’s also essential to acknowledge the experience of the people working in the system and, like the football teams, that their own knowledge can still be used in conjunction with the data to create change. Data doesn’t mean abandoning that.

Teamwork also doesn’t just have to be within one ward, or one organisation. For so long success has been measured in terms of the metrics reported by individual organisations, which results in competitive and at times combative relationships and behaviours. The future of the NHS must lie in everyone working together and learning from each other rather than further damaging and energy sapping reorganisations of the systems structure.

It must focus on a future where transparency, trust, confidence and support are modelled and evident in the day-to-day working behaviours and practices of teams across whole health systems. Systems must learn to understand together the gains they want to deliver for patients, how they are going to achieve the gains, and agree system-wide metrics for success and measure the trajectories.

Many individual trusts are already making great strides in embracing new leadership cultures, where open, collective approaches are building increased trust within and between teams and the confidence to approach innovation and change. The same now needs to happen between the leaderships of different organisations across systems.

British sport, after nearly two decades of consistent improvement, is something the NHS must take time to understand and learn what might benefit all patients.

References:

Kings Fund: The NHS Long Term Plan explained https://www.kingsfund.org.uk/publications/nhs-long-term-plan-explained

New York Times Magazine: How data (and some breathtaking soccer) brought Liverpool to the cusp of glory, Bruce Schoenfeld, May 22 2019 https://www.nytimes.com/2019/05/22/magazine/soccer-data-liverpool.html

Jo Cubbon is chairman of Alamac Ltd