Quality governance survey shows just how much more needs to be done to bring quality governance in the NHS up to scratch. Jennifer Trueland reports

Same page: boards must engage staff in quality improvement

When the Care Quality Commission next knocks on the door of your organisation, just how confident are you that there will be no surprises?

A survey of more than 200 senior leaders in the healthcare sector found that around a quarter were either “nervous” or “not confident at all”, with just a third saying they were confident there would be no surprises.

The research on quality governance, conducted by HSJ in association with BDO LLP, found that while some boards of healthcare organisations took the issue seriously, this was by no means universal.

For example, just over a quarter (28.5 per cent) said their board was “directly involved” in the detailed design of quality governance, with almost a third (32.6 per cent) saying it was tasked to others and approved.

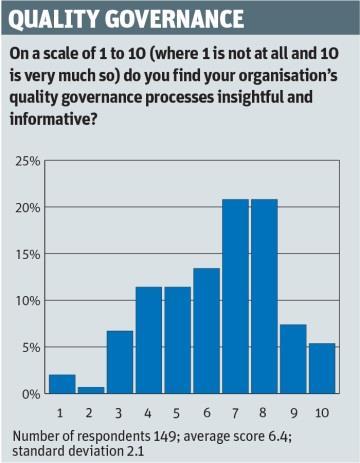

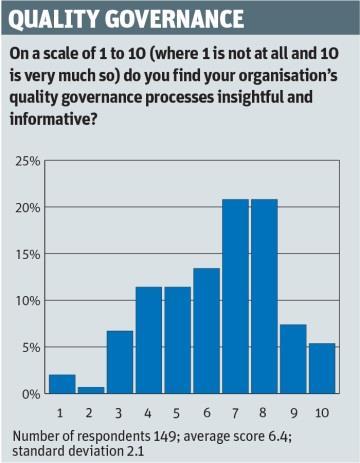

And although some respondents rated their organisation highly in terms of having insightful and informative quality governance processes, almost half were less positive, giving a less than ringing endorsement of six out of 10 or lower.

Little surprise

The results came as little surprise to Simon Dowse, BDO director in healthcare advisory. He points out that although most respondents – who included director level NHS managers and non-executive directors – said staff engagement was crucial to strong quality governance, this was not necessarily played out on the ground.

While 82 per cent strongly agreed that staff engagement was key, almost half of those who responded (45.5 per cent) did not feel that the board of their organisation tested and assured itself that staff were positively engaged in quality governance.

‘If you believe that staff engagement is crucial to quality governance then you have to take it seriously’

Those who did, however, gave numerous examples of how this was done, ranging from staff surveys and listening events to quality and safety walkabouts byboard members.

“If you believe that staff engagement is crucial to quality governance then you have to take it seriously, and take steps to assure yourself that staff are engaged,” says Dr Dowse. “Staff surveys are very passive, and don’t have strong board involvement. Effective quality governance must involve active staff engagement.”

Most respondents felt that their organisations use quality governance processes as active tools to communicate and engage, as opposed to using processes only for monitoring performance. A total of 55.2 per cent agreed that this was the case, with 16.4 per cent agreeing strongly.

Only 2.4 per cent disagreed strongly that this was the case, 18.2 disagreed (but not strongly) and almost a quarter (24.2 per cent) neither agreed nor disagreed.

Almost all respondents agreed that their organisation used mechanisms such as staff surveys or non-executive ward visits to add insight to governance findings and themes. The extent to which it happened varied, however, with 32.9 per cent saying this happened “always” compared with 37.2 per cent who said it happened “usually” and a quarter saying it happened “sometimes”.

Design of processes

But what about the design of the processes in the first place – and how closely they match with the organisation’s core strategy?

There was little unanimity on whether respondents felt that their organisation’s board was closely involved in the detailed design of their quality governance. While 28.5 per cent said that the board was directly involved and 38.9 per cent said that the board had active oversight, just under a third (32.6 per cent) said it was tasked to others and “approved”.

Respondents were asked to rate (on a scale of one to 10) how insightful and informative they found their organisation’s quality governance processes.

Around one in 20 gave an impressive 10 out of 10 and 7.4 per cent gave their organisation a nine, but some 45 per cent gave their organisation six or below, and 2 per cent reckoned their organisation deserved just one out of 10.

“This is really not good news,” says Dr Dowse. “There’s no good reason why quality governance processes shouldn’t be insightful and informative, so everyone should really be scoring it at an eight or above. That so many are rating it at six or under is areal worry.”

‘If the primary task is to improve the quality of services, the strategy should be central to planning practice’

Most respondents felt that their quality strategy was central to their organisation’s business and strategic planning processes, with almost four in 10 saying it was “at the core” and a similar proportion saying it was “aligned”

Just under a fifth of respondents felt it was “referred to” while 4.2 per cent said it was not relevant.

“If the primary task [of NHS organisations] is to improve the quality of services, then the quality strategy should be central to business and planning practice,” says Dr Dowse.

But what about when things go wrong? It seems that in most organisations board members directly engage on selected serious incident processes and root cause analyses.

The extent to which this happens varies, however, with just over a fifth (22 per cent) saying it happens all the time, 36.4 per cent saying it happens regularly, and just over a quarter (25.8 per cent) saying it happens occasionally. Only 3 per cent said it never happened, while 12.9 per cent felt it happened “rarely”.

Dr Dowse says that in some of the best performing organisations he has seen all board members – executive and non-executive – actively involved in serious incident processes, and most gained value from the experience.

If healthcare organisations properly design quality governance processes, assure themselves that staff are engaged, and make the most of intelligence gathered through their quality report or similar, then they will be able to face regulators with more confidence, says Dr Dowse.

“What this survey shows is that, even in the best of organisations, quality governance isn’t strong enough.

“It’s hard to predict with certainty what the CQC will say and even the best organisations will be nervous about the CQC coming,” he says.

“But organisations with strong quality governance, where the board knows and is assured that staff are fully engaged, will certainly be in a better position.”

Simon Dowse on real engagement

Not only is good quality governance achievable, it is crucial. If “we” (by which I mean the NHS, its regulators, educators and also its advisers) were getting quality governance right, we would expect to see far more positive survey responses. While 98 per cent of those who responded to this HSJ/BDO LLP survey believe that staff engagement is key to strong quality governance, that strength of belief is not mirrored in the rest of the survey.

In our experience at BDO LLP we find good quality governance in organisations where staff really understand its purpose, know how it actually works and believe in its value. We find good quality governance where the board and its immediate community are proactive participants in process and process design rather than passive recipients. If the primary task of NHS organisations is really to protect and improve quality then we must aim for real, heartfelt engagement at all levels with quality governance within organisations.

Sadly, our experience of working with organisations on quality governance systems and processes shows that they often also fail to recognise and tap into the earnest desire of staff to get it right. You have to take time to explain, share, reflect and openly learn from issues and failures to make quality governance work and draw it right into the culture.

To get engagement you also have to make the information about quality insightful and meaningful to staff. This is often not the case, as indicated in the survey results (see the “quality governance” graph, left). We often find that rich sources of quality information, such as complaints and clinical audits, are underused or not shared.

The bar for quality in the NHS has been rising. Much has been done to make quality more visible, regulators have materially changed their approaches and most importantly public expectations have risen and shifted. There are encouraging points in this survey - notably that board members get directly involved in serious incidents and root cause analyses.

Overall, however, these results should make us worry about what needs to happen to raise the bar for quality governance further and that’s within organisations.

The next, and arguably even more challenging, evolution will be to determine how you govern quality at the interface between organisations and services.

Given the challenges of the NHS Five Year Forward View, we need to do what it takes so that next time we run such a survey the distribution has unequivocally shifted towards the positive.

Simon Dowse is director, healthcare, at BDO LLP

No comments yet