Dr Tim O’Hanlon explains why steady advancement is the key to improvement, not a transformational idea or a breakthrough

Many health economies look for that one solution which will reduce attendances at A&E. Have GPs open for longer hours and at weekends… open a walk-in centre…

In a study in the Midlands there was no correlation between the opening hours of GP practices and the attendance rates of patients from those practices at A&E.

In another example, a walk-in-centre treated 42,000 patients in a location that saw 100,000 patients in its local A&E but attendances at that A&E increased.

There is no silver bullet, but there are lessons to be learned from elsewhere.

In the world of sport, David Brailsford of British cycling team fame settled on the concept of the “aggregation of marginal gains” as a way of making a significant number of incremental changes that cumulated into a transformational change. And similar approaches – under different names – have been in use in other sectors for some time.

All of these approaches boil down to a single idea, that identifying and implementing improvements, however small, will lead to more reliable change than hoping and searching for One Big Solution.

How to save 8,000 ambulance attendances

Let’s look at a fictitious case of ambulance attendances as an example. If the one patient that is transported to A&E each week from a local youth hostel can be cared for in a different way, that is 52 ambulances a year not arriving at the front door of A&E.

By increasing the facilities and medical cover at the walk-in-centre 14 ambulance transports a week could be avoided. The Friday night revellers could be treated at a temporary facility in the town centre – that would be 12 ambulances per week.

The worried parents, calling an ambulance to go to A&E, because they have no one to talk to about their child’s condition – up to 20 per week. The re-admissions from the surgical assessment unit – 20 per week.

There is no silver bullet, but there are lessons to be learned from elsewhere

Primary care units routing avoidable transportations to A&E – 18 per week. Known, frequent service users for whom there is no care plan – seven per week. Nursing homes routing DNR patients – seven patients per week.

A minor injuries unit without X-ray links to the acute – 14 per week. Inconsistency in decision making by ambulance crews, where some would transport and others might find a different option – 14 per week. The impact of social marketing eg “blood in your pee”, five per week.

These are all small projects but the potential to reduce ambulance attendances at A&E, through these and similar changes is nearly 8,000 per year for a typical department. Yes of course it would cost money but how significant is the gain?

Identifying waste - the “Hidden Hospital”

- Every hospital consists of two hospitals – the efficient one and the one where there is waste. This is the “Hidden Hospital” and it costs a lot of money to run it:

- A trust has to cancel 5,000 outpatient appointments in a year – how many doctors and nurses would it take to run the 166 clinics to replace those appointments?

- Avoidable blood tests, scans and X-rays that are completed in A&E every week – how many staff are required to complete that level of diagnostics?

- A theatre suite cancels two procedures every day because of blocked beds or poor pre-op assessments – equating to 500 procedures per year. How much theatre time, consultant, anaesthetist and other theatre staff time is “hidden” replacing those procedures?

And hidden costs don’t only relate to direct patient care…

- A trust of 10,000 staff with an absenteeism level of 4 per cent – how much is the “hidden” cost of covering for 400 people every day? Not just the bank or agency cost, but the management time spent finding substitutes, the processing of additional paperwork, dealing with the variation in levels of care.

- 144 people push records around in trolleys every day – even at a modest salary that is more than £2m per year.

- How much time is wasted at meetings where no decisions are made? Let’s say that, in a hospital of 10,000 staff each person wastes one hour per month at a pointless meeting? What is the “hidden” cost of that time?

Identifying hidden costs

The cost of poor quality is a concept that other sectors have sought to address for decades. Such costs are seen in three principle categories, all of which are readily transferable to healthcare:

- Prevention: How little is spent on genuine prevention and lifestyle improvement? The “hidden cost” of not doing this might be realised only in 10 or 20 years - but it is still a cost of poor quality.

- Appraisal: How much cost is associated with appraisal e.g. auditing, inspecting, checking?

- Failure: How many cost reduction activities have caused unintended consequences that ended up creating more cost than the problem they sought to solve?

It is easy to understand why people become distracted with the costs above the water line – because they are often high profile (the Francis report cost ~ £13m) but beneath the surface there is the rest of the iceberg – the chronic waste that continues year after year and for which innovative staff find “workarounds” (another “hidden” cost - how many staff are consumed doing workarounds or rework?)

What is the cost of your hidden hospital?

Three steps to tackling hidden costs: Compliance, Culture, Competency

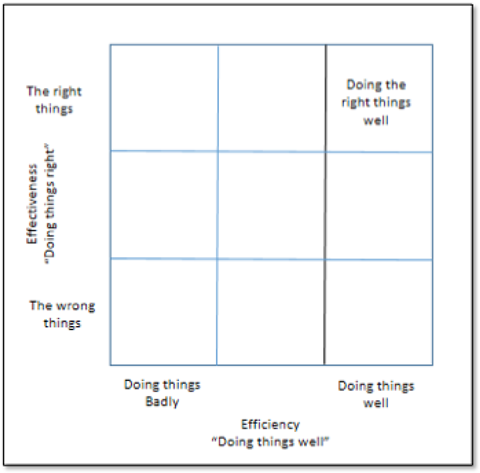

For improvement to become the way of doing things, any organisation needs to understand its need for compliance. Compliance needs to balance effectiveness (doing the right things) with efficiency (doing things well).

Let’s imagine a two by two matrix (See above) – on one axis effectiveness (doing the wrong things or doing the right things); on the other axis efficiency (doing things badly or doing things well).

Let’s suppose the bottom left of the matrix is doing the wrong things, badly. Do we really want to make sure people comply in such an environment? How about doing the right things badly – also not an optimum solution. How about doing the wrong things well – surely not?

Competency to deliver improvement is more than just giving people a set of tools and techniques

If compliance drives an organisation to do the right things well – then; compliance adds value.

Having the right culture is not inevitable. Telling people what the culture must be does not guarantee the right culture.

Culture evolves over time and it can be positive – stimulating innovation, creativity, team work and improvement or it can become negative - where mistakes are hidden and not used to drive improvement, blame is the first port of call when something goes wrong and bad targets drive bad behaviours.

Telling people that they have a duty of candour, without addressing the underlying fear of exposing errors, does not an “open reporting environment” make (Black Box Thinking by Matthew Syed, offers some insights here).

Competency to deliver improvement is more than just giving people a set of tools and techniques. Many organisations “Sheep dip” people through improvement training programmes and they then never use what they have learned.

Competency is not just about the technical side of improvement, it also requires a mechanical element i.e. a structured approach to improvement, where priorities are based on overall strategies such as patient quality, safety and experience and where the changes towards which people are working are clearly evidence-based.

Achieving the desired breakthrough takes constancy of purpose and discipline to turn great ideas into sustained improvements

This ensures that people understand not only how to deliver and quantify the improvement but also – crucially - why improvement is required.

There is also an interpersonal dimension to competency – the attitudes and behaviours that enable people to work collaboratively to deliver beneficial and sustainable change.

This is often compromised by the lack of time people have to devote to genuine improvement tasks. People can work to solve problems but these are often “quick fixes” failing to address the underlying root causes – so the problems recur over and over again.

Conclusion – sustained improvement not One Big Solution

Where there is a particular exposure or sustained pressure, a series of incremental improvements can systematically improve the situation. However, many people look for the silver bullet; the one solution that will solve everything – the breakthrough or transformational improvement.

Of course these can happen and sometimes do. More typically however, teams are assembled and disbanded, priorities change, leaders come and go but the elusive breakthrough never happens and frustration abounds.

Achieving the desired breakthrough takes constancy of purpose and discipline to turn great ideas into sustained improvements.

The one big solution is not a solution at all, but rather an approach which keeps the small changes coming and makes them count.

Dr Tim O’Hanlon is chief operations officer at GE Healthcare Finnamore Ltd

No comments yet