Dr Rob Sheffield talks about how leaders in the health sector can foster creativity and innovation in their teams

I decided to write a book to show how leaders are learning to enable creativity and innovation in their teams. Part of my motivation was fuelled by the dissonance experienced between our everyday work with leaders, and the news grabbing headlines:

“We now observe a huge divide between the modest trust in institutions of business and government and a pitifully low level of confidence in their leaders. Over two-thirds of the general population do not have confidence that current leaders can address their country’s challenges… (Edelman R., Edelman Trust Barometer, 2017)

But the report also gives grounds for hope. Seventy five per cent of the survey respondents believed that business could both increase profits and improve the conditions in communities where it operates. And, of those unsure as to whether the system works for them, 58 per cent trust business the most.

You can have creativity without innovation, but you can’t have innovation without creativity

Over the last 25 years, it’s been a fascinating and fortunate time to be involved in leadership development. The paradigm has altered, away from the focus on the leader as a heroic individual, to one of leadership as a more distributed and relational process.

And my experience and that of my colleagues is that leaders are playing a key role, in bringing diverse people together, to develop novel solutions that improve the lives of the people they serve. I wanted to write this book to give voice to these learning leaders.

Working with leaders and innovation in the health sector has shown some broad patterns:

-

The workforce is hugely committed to purposeful change. This energy is a huge asset for the sector.

-

Improvement ideas are generated constantly – the sheer motivation of everyone involved ensures this.

-

Implementing ideas is often harder. Tight resources – money, time, senior support, attention… – mean that, too often, exceptional effort is needed to turn concepts into action.

-

If ideas prove themselves, then spreading them is even tougher. Idea reinvention is very common across the health sector.

Fostering creativity

Organisational leaders, at many levels, experience frustration, and sometimes guilt, through too great a focus on operational cycles, and too little attention to future development. Leaders worry about retaining and developing their staff, and they worry about staff burnout.

Sometimes, they feel they are “reinventing the wheel” and may find it difficult to evidence the impact of initiatives.

Creativity is the development of novel and useful ideas, whereas innovation is the process of value realisation through implementing novel ideas. You can have creativity without innovation, but you can’t have innovation without creativity. And innovation is very topical.

Research and teaching means from the 1950s onwards mean that we know plenty about developing the human capabilities of creativity and innovation. In 1961, Mel Rhodes collected 56 definitions of creativity and synthesised them:

-

Creative product: How creative are our work outcomes? These may be products, services, processes, business models, markets… And how do these align with organisational strategy?

-

Creative process: This looks at how ideas develop through stages, helped by tools, rules and practices. This is the area of skills training.

-

Creative press: The perceived health of the work climate has a huge impact on how much “extra” effort people choose to put into their work. The biggest factor affecting climate is leadership.

-

Creative person: What are the different problem solving styles of people, and how do these influence the novelty and feasibility of their ideas?

Enabling creativity in teams

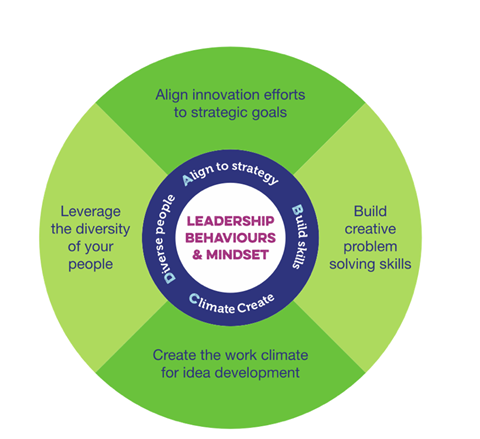

We captured this in our ABCD model, to provide an integrated structure for introducing creativity into organisations:

In the book, I describe nine cases of real leaders learning to enable creativity in their teams, from healthcare, law, technology and education. Here is a brief summary of two:

We trained Liam and his drug and alcohol dependency team in a creative problem solving process to help them explore and redefine challenges; generate many potential solutions; and shortlist promising solutions. They then applied the learning, working with key internal and external stakeholders. They worked through a divergent thinking stage, generating many imaginative possibilities, then a convergent thinking stage, prioritising the most promising solutions.

Their subsequent design proposal proposed an integration of services, with new partners. It was successful: they were commissioned to extend their services across their county.

Dr Michael Kirton’s theory and measure on adaption innovation is useful. Those with a more “adaptive” style prefer to use more structure in their problem solving, and to “tweak” existing approaches. Those with a more “innovative” approach prefer to use less structure, and often want to apply approaches different to what prevails.

Ted is the speciality lead for the emergency department of a large hospital trust in the south of England. He won a place on a regional healthcare leadership development programme. On the programme, Ted completed the adaption innovation profile. His profile score of 82, placed him as a strong adaptor – more adaptive than around 75 per cent of the population.

If ideas prove themselves, then spreading them is even tougher. Idea reinvention is very common across the health sector

He worked with a colleague, Jo, to address the challenge of safe patient flow in and out of their accident and emergency department. Jo, a strong innovator, broadened the solution, beyond the immediate boundaries, and suggested involving the wards to share ownership of the problem.

As Jo developed the idea with others in the hospital, Ted supported her by giving legitimacy to the idea, reassuring people in meetings, and providing Jo with political support. They complemented each other, and Ted’s increased self awareness was fundamental to that. As he said:

“…That’s the most important thing I learnt – that my weaknesses don’t mean I’m a bad leader – I just need to play to my strengths and that’s OK.”

Our clear experience is that leaders and their teams learn quickly how to be more creative. The learning “sticks” when they complement skills training with a supportive work climate, using the thinking diversity they possess, and do all this with innovation clearly aligned to strategy.

Leaders should note that the approach is a highly engaging one for the people involved. Often, people have fun, use their imagination and produce outcomes that traditional meetings don’t achieve.

These are skills that people and organisations want for the future. And we already know how to develop them.

No comments yet