In light of an evaluation of the NHS Leadership Academy’s Aspiring Chief Executive programme, it would seem timely to consider what we expect of our NHS chief executives, and the demands we place upon them. Stephen Hart has more.

Senior leadership in any organisation or system is an extraordinary privilege. These hugely influential roles require exquisite blends of knowledge, skills, experience, and behaviours. It’s right that we’re highly selective about who occupies these roles, and how we support and develop those who aspire to them.

In association with

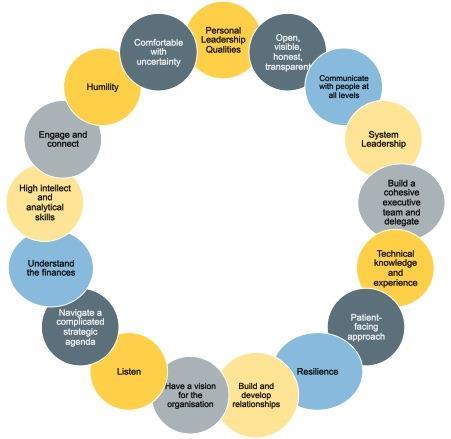

Our evaluation of the NHS Aspiring Chief Executive programme has highlighted themes around what makes an effective CEO and highlights tensions in the context in which they lead. It offers a model of what makes an effective CEO. Rather than a prescription of “types” of people, the model (see diagram) is a synthesis of the tensions CEOs operate in. The research is based on 120 indepth interviews with chairs, CEOs, staff members and colleagues in social care and at national level.

The programme is a collaboration between the NHS Leadership Academy, which as of 1 April 2019 is part of the NHS People Directorate in NHS Improvement/England, and NHS Providers. It was established to create a talent pool of potential CEOs who had been supported to develop the necessary knowledge, skills, attitudes and experiences. The evaluation demonstrates the programme’s impact on participants’ leadership in these areas, with some important additions:

1. Leading for inclusion: This programme has demonstrably changed participants’ attitude, and impact, on creating and sustaining inclusive cultures. The evidence of impact is based on improvement in WRES measures in participants’ organisations. Some participants have introduced reverse staff mentoring from junior BAME staff – experienced during the programme – for example. These, and other interventions based around hearing others’ lived experience, has enabled CEOs and their boards to have the challenging conversations that may previously have been avoided.

“The diversity piece was the biggest difference for me. I’ve always prided myself on trying to be very fair and inclusive, but I think I was doing that in a passive way rather than in an active way.”

2. Commitment towards system leadership: This is underpinned by an orientation to the wider population, not one organisation. Beyond essential operational activities, the programme encouraged participants to become more concerned about health inequalities and the public health agenda, and the ability to influence and create impact.

3. Personal purpose: Participants described how the programme helped them crystallise their personal purpose and values and be more open and explicit in sharing it. Leadership starts with “why” and supporting our most senior leaders to understand and articulate theirs enables them to create and empower the teams, organisations and systems they serve.

“It gets you to think really hard about who you are. What am I here for? What am I hoping to achieve? What kind of leader do I want to be? How does it feel to be on the receiving end of me?’

System tensions

Interviews described three key areas of tension:

1. Collective leadership, individual blame: Individual accountability, visibility and prominence makes the CEO role a lonely one. CEOs operate in a pressurised context where there is intense scrutiny by regulators, commissioners, the public and the press. The evaluation highlights the importance of access to a supportive network of peers and advisors, of the kind participants gain on the programme. The “risk of ending up as the scapegoat for poor performance” is one recognised by the majority of interviewees in this study.

“You can see why people go into these jobs and fail, and then they get branded as useless because they’ve not been able to do a job which probably wasn’t doable anyway.”

Participants form valued networks, rejecting notions of heroic, individual leadership for a collective, team-based approach founded on clear values and real engagement with staff and the public.

2. Transformation versus stability: Around three quarters of participants and other newly-appointed CEOs explicitly see themselves as agents of change. The programme’s aim is to develop CEOs able to lead in – and transform – the current system. In investigating the experience of applying for CEO posts, the study identified some potential blockages; these include fewer CEO posts in organisations that might be deemed suitable for a first-time CEO and risk aversion amongst chairs looking for a new CEO.

“… if you’re a chair who is perhaps risk-averse because it’s very difficult and they’re getting beaten by a regulator…and where you might have less organisations around, there’s an awful lot of experienced chief executives on the move… they [the chair, board and governors] have a tendency often to lean for people who are known or experienced.”

Experienced CEOs are already leading change and transformation, but can new ones emerge? Experience of being a CEO cannot become a pe-requisite for being one. The rich pool of diverse NHS talent needs the opportunity to break through to the most senior levels.

3. Organisation or system leadership?: The study highlights the challenge of doing the strategic work of building diverse relationships across the system to achieve collective aims while concurrently delivering on performance targets with limited resource. Throughout three cohorts, the contradictions between the programme’s emphasis on system leadership, population health and staff engagement has been in tension with an environment that rewards organisational competition and performance metrics. Most interviewees felt the characteristics required to be an effective CEO have changed in line with the direction of travel described in the NHS long-term plan. They point to a style of leadership able to navigate ambiguity and work and influence across different sectors. Such leadership is based on relationships and influence, not power and hierarchy.

“The way leadership currently exists won’t be how it is in the future – leaders need to be able to take on a multiple perspective – the configuration of organisations is changing rapidly. They need to be prepared for that and they need to be enabling that change and leading that change. We may need to expand what we see as success – is success being a chief executive in the organisation we recognise now?”

The CEOs named in this year’s Top 50 chief executives list - and those who aren’t - deserve recognition for their public service. They represent the very best leaders of our country. Our NHS faces huge challenges to overcome the cultural and organisational barriers to necessary transformation. Trust CEOs have the values and sense of purpose to respond to the ask of leading system change in the NHS. They deserve to be empowered and supported from across all levels of the service, not least by an enabling and supportive regulatory environment that reflects the compassionate and inclusive leadership that we know creates improved patient care, better health outcomes, and more efficient practice.

What makes for an effective CEO? Source: The Institute for Employment Studies (IES)

A summary of the evaluation report is available on the NHS Leadership Academy’s website.